The Place of the Arts in Times of War: Civic Responsibilities of The Phillips Collection during WWII

From the Archives

Makeba Clay Fellow Xin Zheng explores The Phillips Collection’s civic responsibilities during WWII.

“In 1918 I incorporated the Phillips Memorial Gallery…to create a memorial worthy of the virile spirits of my lost leaders—my father, Major D. Clinch Phillips…and my brother, James Laughlin Phillips.”—Duncan Phillips, A Collection in the Making, 1926

The Program of Activities of the Phillips Memorial Gallery,” 1942, Brochure, People’s Archive, Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library, Washington, DC

The Phillips Memorial Gallery (now known as The Phillips Collection) was a deeply personal endeavor for founder and first director Duncan Phillips. He envisioned the gallery to be a place where “visitors can be comfortable and at home.”[1] This dedication to creating an intimate atmosphere was especially important to Phillips at the onset of the Second World War as he wished to extend the comfort that art offered him to the public. Before the United States was officially involved in the conflict, Phillips delivered a fortifying speech, The Place of the Arts in the World Today, at the Phillips Memorial Gallery in December 1940. His initial speech was later adapted to radio talks, lectures, and pamphlets. In January 1941, The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, a major regional newspaper, even published the speech: Art is the antithesis of war. Art is the greatest natural language between the different tribes and races. It is the symbol of the creative and social forces which unite men, the rallying point of opposition to all those destructive anti-social forces which divide them…How can art go on in wartime, when all it signified seems canceled and contradicted? Only by art’s acceptance of war’s challenge. Only through the searching of our souls as individuals, only by knowing ourselves, deciding how best we can serve the cause, the defense of art and culture, of mental and spiritual freedom…[A]rt must be the last stand, as it will be the eternal stronghold of the individual.”[2] Phillips’s aspiring messages such as “art can and must serve humanity,”[3] “to have faith in art…is to hold to our faith in men,”[4] and “art must be the last stand, as it may be the eternal stronghold of the individual”[5] resonated well with Americans especially after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. Phillips’s words rang so clearly in the United States that other museums such as the Art Institute of Chicago asked him to deliver the speech again in their location.[6] Indeed, the Phillips Memorial Gallery was an exemplary museum that served as “the last stand.” Phillips acknowledged the value of art even before war was declared in Europe. When Oskar Kokoschka, an Austrian artist, fled to Great Britain with his wife in 1938, the Phillips Memorial Gallery started to purchase Kokoschka’s paintings to financially support him.[7] Kokoschka’s View from the Moldau Pier IV is the first of many paintings that Phillips acquired during the war years (Fig. 1). As the war waged on, Phillips continued to be concerned with the dismal situation in Europe. After Germany occupied France in 1940, the Phillips Memorial Gallery welcomed a retrospective exhibition of Georges Rouault to raise awareness of the devasting war. Rouault was a French painter whom Phillips believed to have expressed “a sorrowful exposure of human cruelty and a penitential meditation upon the agonizing repetitions of Calvary” (Fig. 2).[8]

Fig. 1: Oskar Kokoschka, Prague: View from the Moldau Pier IV, 1936, Oil on Canvas, 38 5/8 x 51 3/8 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1938

Fig 2: Georges Rouault, Tragic Landscape, 1930, Watercolor on paper, 18 3/4 x 23 1/2 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1931

When the United States officially entered the war in 1941, Phillips dedicated more of his time to ensuring the safety of the gallery as well as fulfilling what he believed to be the gallery’s civic responsibility. Although some important paintings in the collection were transferred to Kansas City and Colorado Springs after the United States declared war, the gallery nonetheless remained open.[9] Phillips’s wife and assistant director, Marjorie Phillips, later recalls: “In wartime Washington, the responsibilities of The Phillips Collection were greater than ever. The most difficult problem to be solved was how to continue its activities and keep it alive.”[10] Prompted by the worrisome atmosphere in the capital, Marjorie’s Emerging from an Air Raid Shelter attested that air raids were of real concern to Washingtonians (Fig. 3). Despite living with constant fear, Duncan persisted. He withdrew from many outside responsibilities so that he could have more time for “writing and for any possible influence [he] might [have] on war time issues and problems about which [he feels] deeply.”[11]

Fig 3: Marjorie Phillips, Emerging from an Air Raid Shelter, 1941, Oil on canvas, 11 3/4 x 17 1/2 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1941

As the United States continued to be involved, the Phillips Memorial Gallery bridged the war front and the home front. In 1942, the gallery presented an exhibition of pictures by British children that were recently painted under war conditions.[12] Phillips believed that his collection could directly contribute to U.S. war efforts when he proposed to the State Department to print Honoré Daumier’s Uprising on pamphlets to be distributed in Europe, claiming that the painting had the power to arouse rebellions in occupied territories.[13] Although the project was never actualized, it showed that Phillips sincerely believed in the power of art in times of war. Early in 1943, the gallery showed a solo exhibition of Chaim Soutine, a Jewish artist whose works Phillips only started to purchase in 1940. Soutine’s paintings were often related to his escape from Lithuania to the countryside of France. Phillips was drawn to Soutine’s “nervous agitation of the modern mind in a period of social conflict and war.”[14] Soutine’s Return from School after the Storm has an especially powerful message, and it was the first Soutine that Phillips purchased (Fig. 4). Soutine painted the picture in 1939 when he an his wife Groth fled to the village of Civry-sur-Serein to hide from the Nazis. One could feel Soutine’s anxiety in this painting, and Phillips saw that as a valuable depiction of what it felt like living under Nazi surveillance. Despite having the chance to come to the United States, Soutine declined and was later taken to a concentration camp.[15]

Fig 4: Chaim Soutine, Return from School after the Storm, Oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 19 3/4 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1940

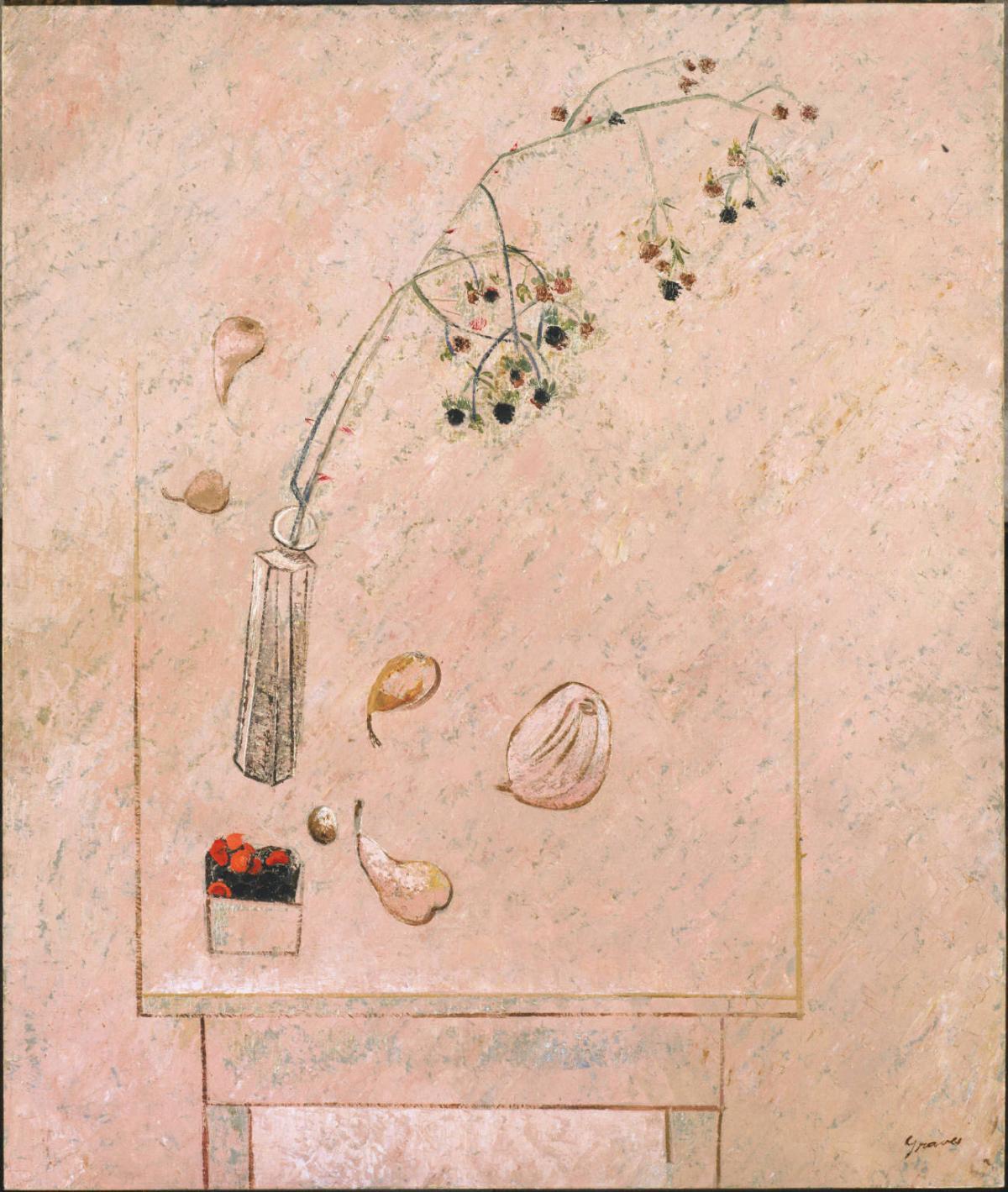

Phillips did not see the gallery solely as a place to raise awareness, for he also viewed it as a space that offered comfort to visitors. In 1943, the Phillips Memorial Gallery presented a solo exhibition of Morris Graves, an American painter whose works recall traditional Chinese painting’s simple and harmonious composition (Fig. 5). To Phillips, Graves’s works were especially important during the war years because his art helped in “healing the wounds of the war.”[16] In other words, the exhibition was consciously designed to offer visitors some relief and a chance to meditate amidst a global conflict.

Fig 5: Morris Graves, August Still Life, 1952, Oil on canvas, 48 x 40 3/4 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1954

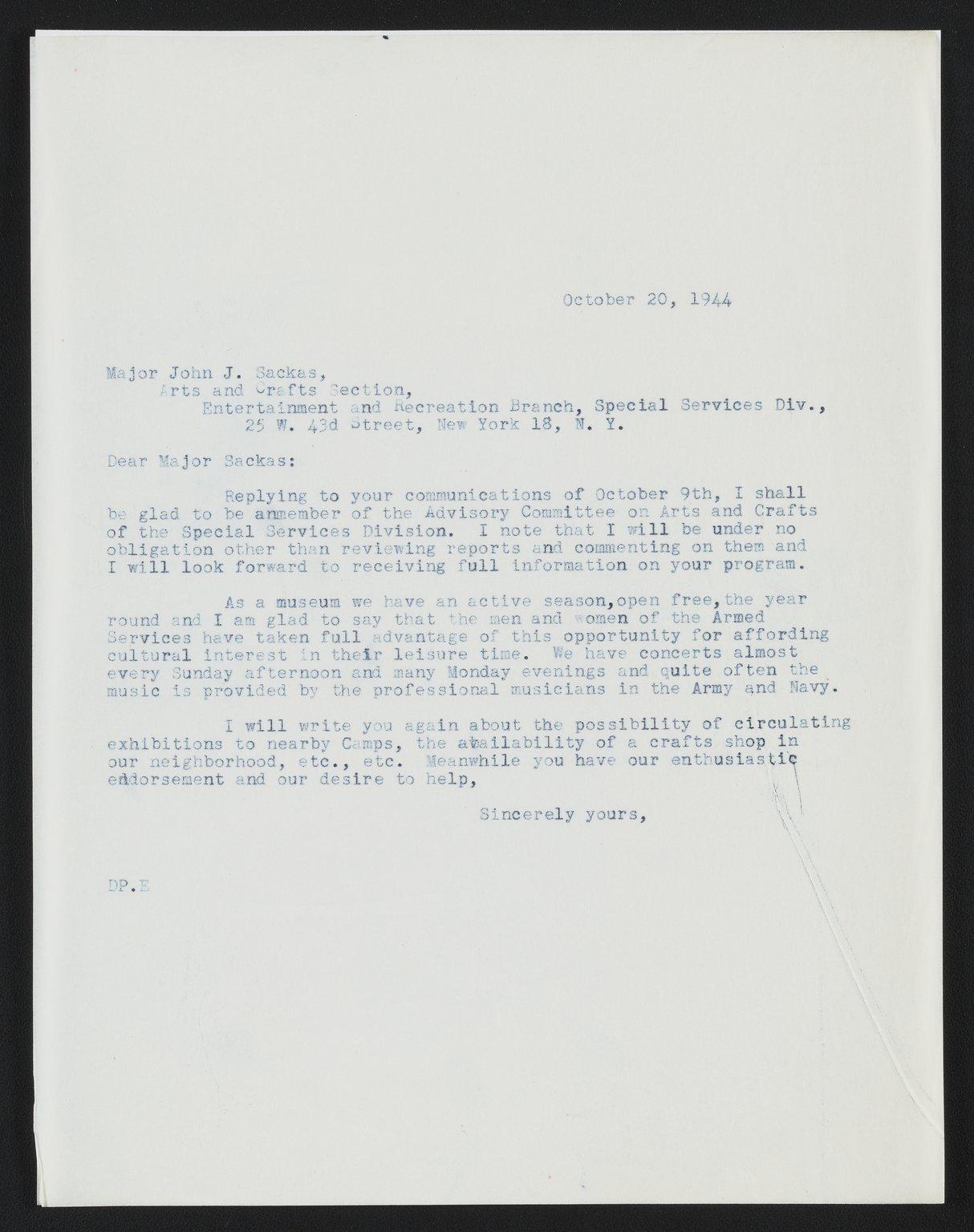

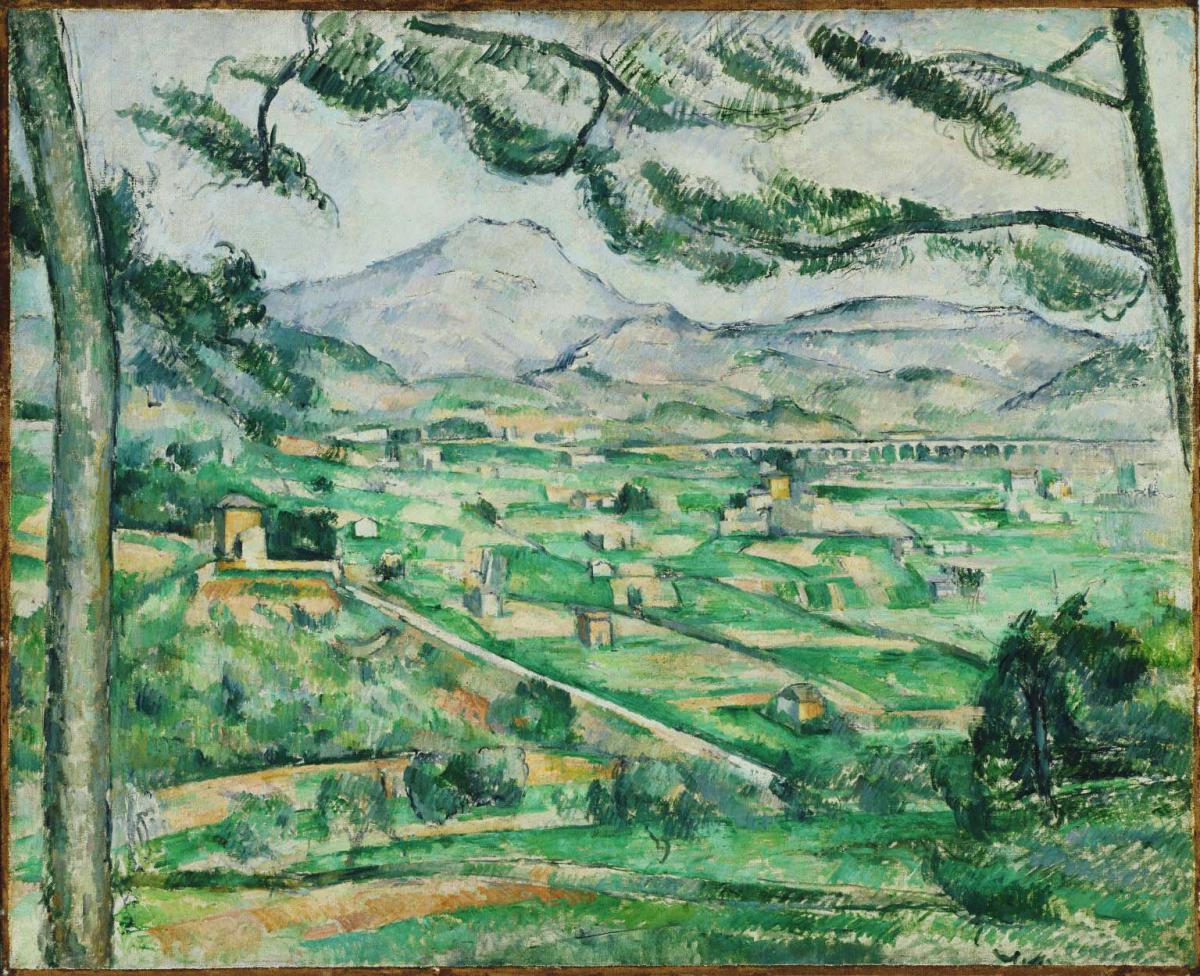

The Phillips Memorial Gallery was also of practical help in the home front. Phillips believed that “in these war times, museums, art galleries, and other organizations are rendering a real service in helping morale by presenting programs for the benefit of the public and especially for men and women in the service.”[17] Thus, Phillips helped the American Federation of Arts to compose an exhibition of works by people in the service, and he also joined the committee on Arts and Crafts of the Special Service Division.[18] Moreover, in those years Phillips invited an increasing number of musicians in the army and the navy to play in the gallery’s concerts.[19] Not only was the gallery interested in helping Americans, but it also had a global perspective. In mid-1943, the Art Gallery of Toronto and the Navy League of Canada wanted to host an exhibition that would provide financial aid for allied merchant seamen who touched at Canadian ports. The Art Gallery of Toronto’s director, Martin Baldwin, expressed to Phillips that the gallery had only one major exhibition since the start of the war, and the museum was in desperate need of support.[20] At first, Phillips declined, citing: “[artworks] should remain where they are and not be submitted to the risk of travel in wartime.”[21] Baldwin, however, insisted the exhibition’s importance for the gallery and the war effort. After careful consideration, Phillips decided to lend Paul Cezanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire to the Art Gallery of Toronto (Fig. 6). The exhibition proved to be a success, raising $25,018.12 with the painting safely returned to the United States.[22]

Duncan Phillips, Duncan Phillips to Major John J. Sackas, October 20, 1944, from The Phillips Collection Archives, Directorial Correspondence: The Correspondence of Duncan Phillips, https://tpcarchives.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/2/archival_objects/2843.

Fig 6: Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, Oil on canvas, 23 1/2 x 28 1/2 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1925

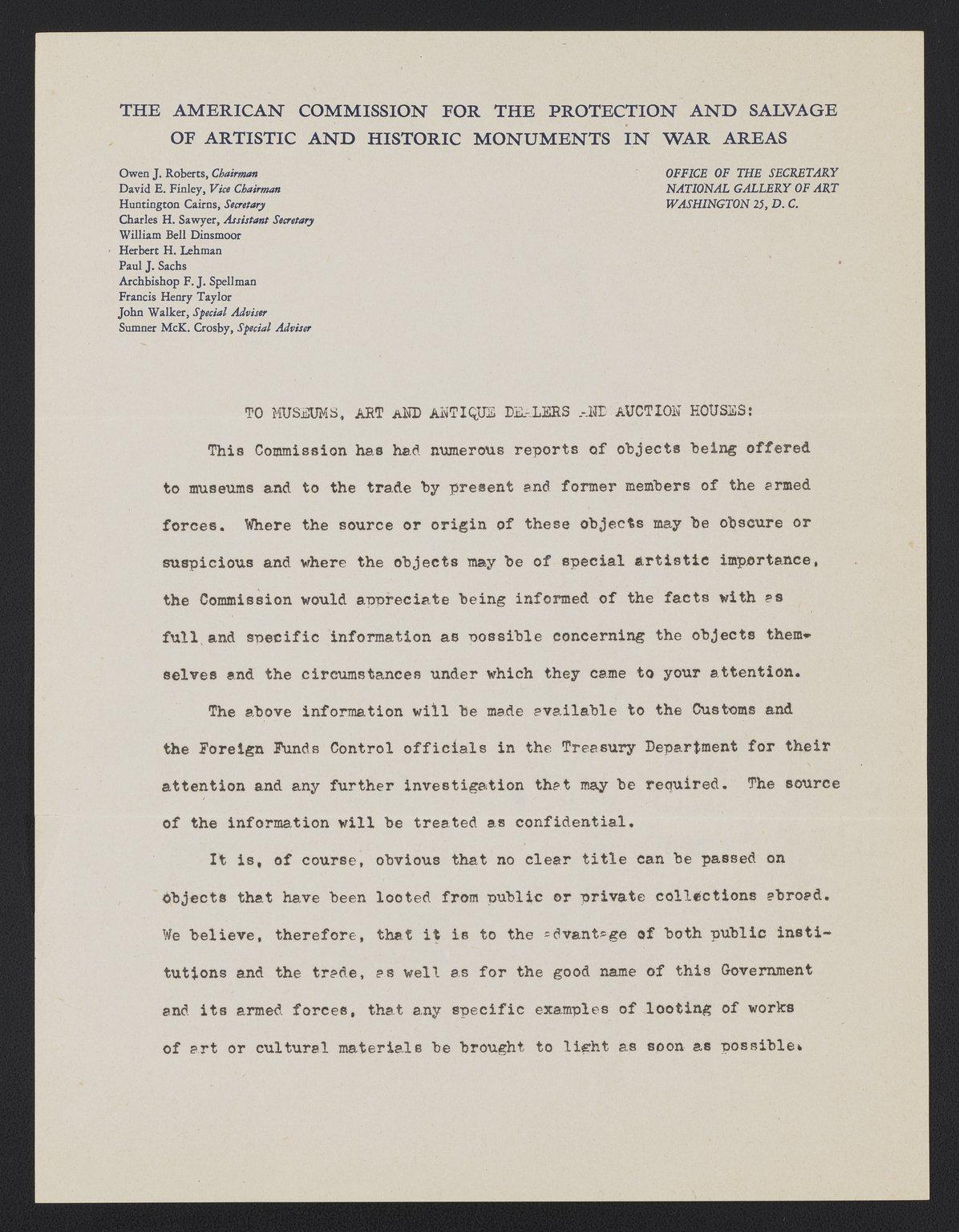

In May 1945, Germany surrendered to the allies, and in September of the same year, Japan surrendered. Before the official end of the war, the Tate Gallery in London eagerly wanted to host a comprehensive American painting exhibition “as soon after the end of the war as possible.”[23] The Tate Gallery envisioned the show as a sign of gratitude toward the United States and also to commemorate the six rooms of the Tate that were damaged during the war.[24] The Tate Gallery expressed their idea to U.S. Secretary of State James Byrnes and reached out to various organizations such as the Art Advisory Committee and the Division of Cultural Cooperation.[25] All American organizations supported the proposed plan, and the Office of War Information suggested that the Tate contact the newly opened National Gallery of Art in D.C. Upon hearing about this exciting project, the director of the NGA, John Walker, invited Phillips to serve as the chairperson of the committee for selecting contemporary paintings. Other members in the committee included Alfred Barr from the Museum of Modern Art, Julian Force from the Whitney Museum, William Miliken from the Cleveland Museum of Art, and Daniel Catton Rich from the Art Institute of Chicago.[26] The members proposed 75 paintings in total and 23 of them belonged to the Phillips Memorial Gallery. Works by John Marin, Maurice Prendergast, and Thomas Eakins were especially well received by the British after the show debuted on June 14, 1946.[27] Simply put, it was not an ordinary exhibition. With strong support from the United States Department of State, it was also a diplomatic tool, and King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon even visited the show before it officially opened to the public. (Fig. 7)

A list of what The Phillips Collection lent can be found at David E. Finley, David E. Finley to Duncan Phillips, December 5, 1945, from The Phillips Collection Archives, Directorial Correspondence: The Correspondence of Duncan Phillips, https://tpcarchives.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/2/archival_objec…

Fig 7: âLest We Forget: Memorials of War, and Events of Peace,â The Illustrated London News, June 22, 1946

After the official end of the war, Phillips and the gallery continued to receive recognition for their tremendous help during the war. In 1947, Phillips received an honorary degree from Kenyon College, Ohio. Several Kenyon professors pointed out that they found the Phillips Memorial Gallery “alleviating and refreshing” during the war.[28] Phillips also received “many letters from museums and university people who had been stationed in Washington for war or special training. They told how much the gallery…had meant to them during that trying and super worrisome period.”[29] Needless to say, the Phillips Memorial Gallery lived up to the standards that were laid out in Phillips’s speech, The Place of the Arts in the World Today. Since Phillips saw his gallery as an institution “with a large, constructive social purpose,”[30] the Phillips Memorial Gallery continued to abide by his vision post-WWII. As a keen internationalist, Phillips dedicated more of his time to promoting American art globally. In collaboration with the U.S. State Department, the Phillips Memorial Gallery, along with other partners of the American Federation of Arts, increasingly lent pictures abroad, first to the 26th International Biennale Art Exhibition in Venice in 1952, then to various other places including West Germany and India. He wanted the world to treasure modern American art as much as European art. The successful Tate exhibition certainly initiated that process, and Phillips’s continuous support of American art in the 1950s and 60s availed the reputation of American art both domestically and internationally. Notes [1] [Acceptance Speech]. Presented upon acceptance of honorary degree, Doctor of Humane Letters, Kenyon College, Gambier, Ohio. [2] “The Place of Art in a War-Torn World.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. (27 Jan.): 2B. (Revision of article published in A Bulletin of the PMG, 1941). [3] [War]. Essay. 1940-41. Formerly MS 94, 3. [4] The Arts in War Time. Pamphlet. Washington, D.C.: NGA, 13. [5] “The Place of the Arts in the World Today,” presented at symposium held at PMG under the auspices of the Washington Dance Association, Dec. 15, 1940. [6] Earle Ludgin, Earle Ludgin to Duncan Phillips, October 12, 1942, from The Phillips Collection Archives, Directorial Correspondence: The Correspondence of Duncan Phillips, https://tpcarchives.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/2/resources/23. [7] George Heard Hamilton, “A Collection in the Making,” in The Eye of Duncan Phillips: A Collection in the Making, ed. Erika D. Passantino (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 32. [8] Marjorie Phillips, “The War Years,” in Duncan Phillips and His Collection (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1982), 212. [9] Duncan Phillips, Duncan Phillips to Marianna Byram, February 5, 1942, from The Phillips Collection Archives, Directorial Correspondence: The Correspondence of Duncan Phillips, https://tpcarchives.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/2/archival_objects/3586. [10] M. Phillips, “The War Years,” 211. [11] Duncan Phillips, Duncan Phillips to George Hewitt Myers, May 5, 1941, from The Phillips Collection Archives, Directorial Correspondence: The Correspondence of Duncan Phillips, https://tpcarchives.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/2/archival_objects/3086. [12] Cited in Erika D. Passantino, The Eye of Duncan Phillips (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), Appendix 662. [13] Grayson Harris Lane, “Duncan Phillips and the Phillips memorial Gallery: A Patron and Museum in formation, 1918-1940,” PhD diss., (Boston University, 2002), 220. [14] Leslie Furth, catalogue entry for the book from Erika D. Passantino, ed., The Eye of Duncan Phillips: A Collection in the Making, museum catalogue, The Phillips Memorial Gallery, 1999 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 228. [15] “Return from School After the Storm,” The Phillips Collection, https://www.phillipscollection.org/collection/return-school-after-storm. [16] Duncan Phillips, Duncan Phillips to the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, 1945, from The Phillips Collection Archives, Directorial Correspondence: The Correspondence of Duncan Phillips, https://tpcarchives.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/2/archival_objects/6668. [17] Duncan Phillips, Duncan Phillips to George Picken, from The Phillips Collection Archives, Directorial Correspondence: The Correspondence of Duncan Phillips, https://tpcarchives.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/2/archival_objects/3088. [18] Ibid. [19] Duncan Phillips, Duncan Phillips to Major John J. Sackas, October 20, 1944, from The Phillips Collection Archives, Directorial Correspondence: The Correspondence of Duncan Phillips, https://tpcarchives.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/2/archival_objects/2843. [20] Martin Baldwin, Martin Baldwin to Duncan Phillips, December 13, 1943, from The Phillips Collection Archives, Directorial Correspondence: The Correspondence of Duncan Phillips, https://tpcarchives.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/2/archival_objects/3325. [21] Duncan Phillips, Duncan Phillips to Martin Baldwin, December 11, 1943, from The Phillips Collection Archives, Directorial Correspondence: The Correspondence of Duncan Phillips, https://tpcarchives.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/2/archival_objects/3325. [22] John M. Lyle, John M. Lyle to Duncan Phillips, June 2, 1944, from The Phillips Collection Archives, Directorial Correspondence: The Correspondence of Duncan Phillips, https://tpcarchives.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/2/archival_objects/3325. [23] Duncan Phillips, Duncan Phillips to Daniel Catton Rich, April 23, 1945, from The Phillips Collection Archives, Directorial Correspondence: The Correspondence of Duncan Phillips, https://tpcarchives.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/2/archival_objects/3344. [24] Caroline M. Riley, “American Painting, 1946,” in Modern American Art at Tate 1945-1980, Tate Research Publication, 2018, https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/modern-american-art-at-tate/essays/american-painting-london-1946. [25] Ibid. [26] Ibid. [27] A list of what The Phillips Collection lent can be found at David E. Finley, David E. Finley to Duncan Phillips, December 5, 1945, from The Phillips Collection Archives, Directorial Correspondence: The Correspondence of Duncan Phillips, https://tpcarchives.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/2/archival_objects/10885; On British reception of the exhibition see “American Art, Paintings on View at the Tate, King and Queen Visit Exhibition,” The Times, June 13, 1946. https://go-gale-com.proxy.library.georgetown.edu/ps/retrieve.do?tabID=Newspapers&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchResultsType=SingleTab&hitCount=42&searchType=AdvancedSearchForm¤tPosition=10&docId=GALE%7CCS134431438&docType=Article&sort=Relevance&contentSegment=ZTMA-MOD1&prodId=GDCS&pageNum=1&contentSet=GALE%7CCS134431438&searchId=R6&userGroupName=wash43584&inPS=true. [28] M. Phillips, “The War Years,” 212. [29] Ibid. [30] C in M, 1926: A Collection in the Making. Phillips Publication No. 5. New York and Washington, D.C., 4.