Shadow and Light: Marjorie Phillips in the Gendered Landscape of 20th-Century Art (Part II)

From the Archives

2022-23 Makeba Clay Fellow Sophie Bennett explores the legacy of Marjorie Phillips’s career as an artist. Part 2 of 2.

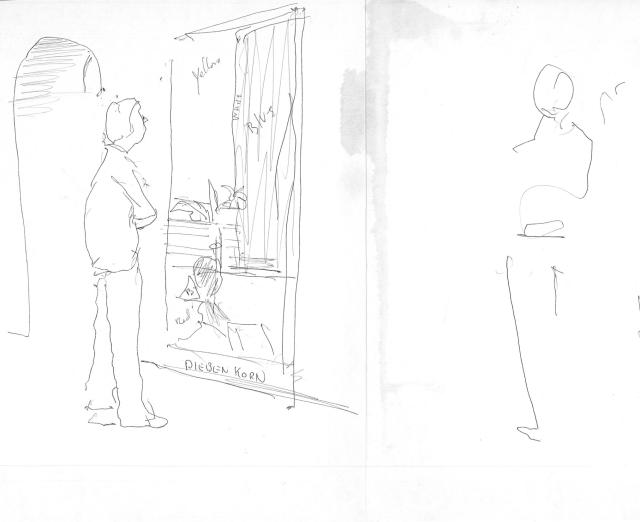

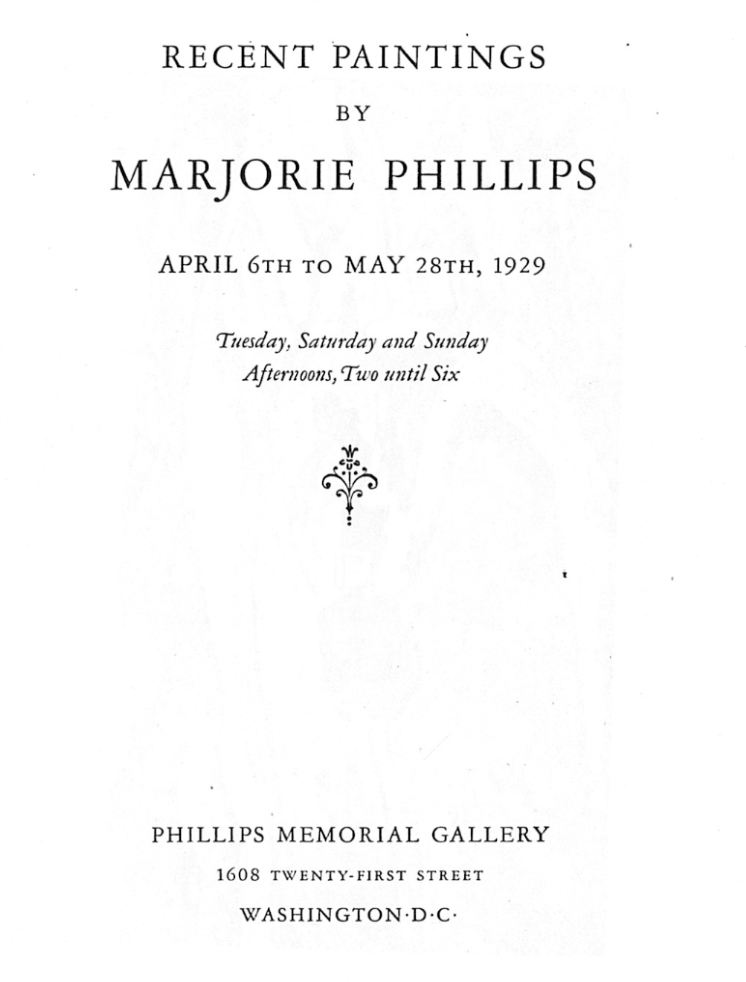

The first section of this two-part blog post delves into Marjorie Phillips’s biography, investigating how her privileges figured into her success as an artist. This section explores how Marjorie’s privileges could not fully circumvent the sexism of the 20th century. Perhaps the most striking evidence of this pervasive sexism comes from critical praise of her work. In a 1929 review of Marjorie’s work, critic Leila Mechlin wrote:

The desire of modernists today is to become as little children, to be able to give forthright expression to not only things seen but things felt. But few are successful in such attainment. Mrs. Phillips is one of the few, and the reason for it is that while gaining maturity in skill she has not lost her freshness of viewpoint, ‘the sweet perfume of Springtime years,’ which Lowell lauded in his great poem on womanhood, and which, once lost, can never be regained.[1][2]

In Mechlin’s view, her success as an artist is a clear product of her womanhood. And to be a woman is, evidently, to be like a child. While Mechlin makes this association between childhood and womanhood as a compliment to Marjorie, the comparison also lends itself to troubling arguments (if women are like children in all regards, what does that say about how people understood the autonomy, intellect, and rights of women at that time?).

Critic Ada Rainey echoed this view, in her review of the same show in the Washington Post. Rainey praised and dismissed Marjorie’s work in equal measure, describing it as “simple,” “homey,” and “wistful.”[3] Thus, even when her exhibitions were celebrated, it was celebrated within the confined expectations and lens of womanhood.[4][5]

In regard to understanding forms of oppression, it seems we often fall into a metonymic fallacy—the tendency to perceive a represented part as “an accurate reflection of the whole for which it is taken as standing.”[6] This is to say that, though Marjorie’s exceptional success as a female artist and museum professional fits into a larger narrative of the efforts to promote the representation of women in the arts, her success did not necessarily indicate or bring about progress for female artists as a whole. To write about Marjorie’s artistic career as though she single-handedly overcame sexism suggests that other women of her time should have been able to replicate her accomplishments through talent and hard work alone. This thinking puts the onus on the oppressed group to lift themselves out of oppression, rather than on the society as a whole. Furthermore, in examining Marjorie’s artistic achievements, it becomes clear that her career was not simply a glimpse of a post-patriarchal society. Rather, Marjorie’s success somewhat depended on the recognized and acceptable forms of power she had within a sexist culture.

In conclusion, Marjorie Phillips’ artistic journey exemplifies the nuanced interplay between gender and privilege in the early 20th century art world. While her marriage to Duncan Phillips and familial connections provided unprecedented access and support, these advantages did not insulate her from sexist readings of her work or lead to the success she might have seen as a male artist. Duncan Phillips’ writings reflect a conscious effort to navigate these dynamics, highlighting Marjorie’s individuality while also revealing the pervasive gender biases of the era. Marjorie’s legacy as an artist, therefore, not only illuminates her own artistic work ethic but also serves as a crucial case study for understanding the broader struggles of female artists—who, as of 2019, make up 11% of all museum acquisitions and are featured in 14% of exhibitions at 26 major museums in the United States.[7]

[1] Mechlin, Leila. The Evening Star (Washington (DC), District of Columbia), April 21, 1929: 32. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers

[2] Mechlin was the first female art critic in the United States, writing for The Evening Star from 1900 to 1946. See Evening Star (Washington (DC), District of Columbia), May 7, 1949: 2. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

[3] Rainey, Ada. “2 EXHIBITIONS OF PAINTINGS INTERESTING.” The Washington Post (1923-1954), Apr 14, 1929.

[4] Linda Nochlin addresses the very idea that “femininity” links women artists in her celebrated 1971 essay for ART news, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Nochlin writes: “While the members of the Danube School, the followers of Caravaggio… or the Cubists may be recognized by certain clearly defined stylistic or expressive qualities, no such common qualities of “femininity”would seem to link the styles of women artists generally…No subtle essence of femininity would seem to link the work of Artemisia Gentileschi, Mme. Vigee-Lebrun, or Louise Nevelson.” See “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” ARTnews, 1971.

[5] That Marjorie’s privileges and achievements were

[6] “Metonymic fallacy.” Oxford Reference.

[7] Burns, Charlotte. “Museums Claim They’re Paying More Attention to Female Artists. That’s an Illusion.” Artnet News, September 19, 2019.