Shadow and Light: Marjorie Phillips in the Gendered Landscape of 20th-Century Art (Part I)

From the Archives

2022-23 Makeba Clay Fellow Sophie Bennett explores the legacy of Marjorie Phillips’s career as an artist. Part 1 of 2.

Duncan Phillips’s devotion to art took many forms. Though many know him as an art collector, first and foremost, he also wrote prolifically about the arts. In 1926, he published his first in-depth writing on the museum, a book entitled A Collection in the Making. The volume included over 100 short biographies of artists from the collection. If you are familiar with our museum’s history, you might be able to identify the artist he describes in this biography:

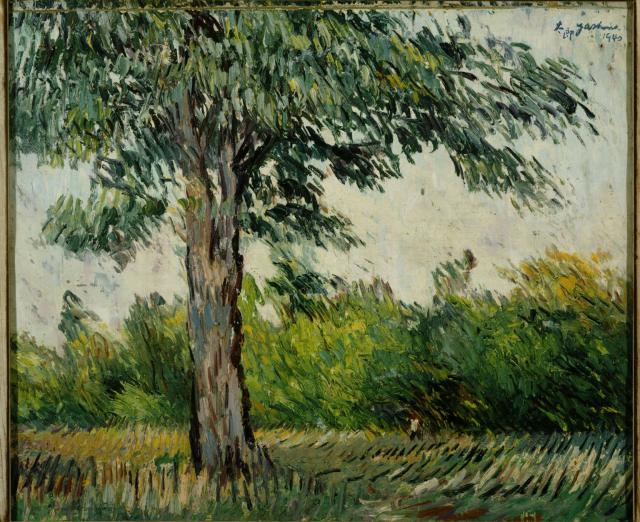

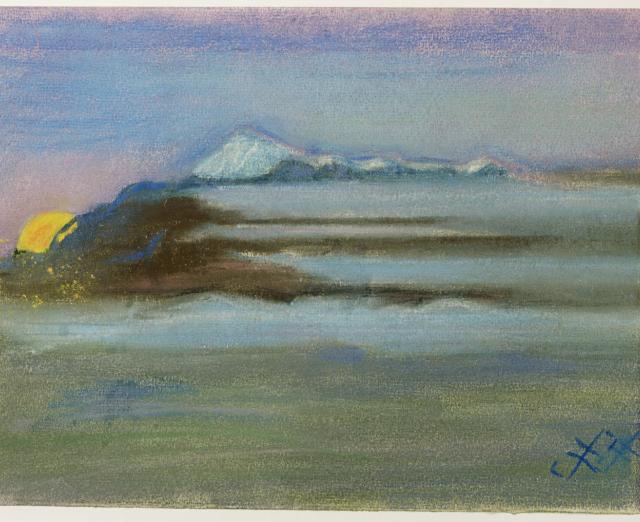

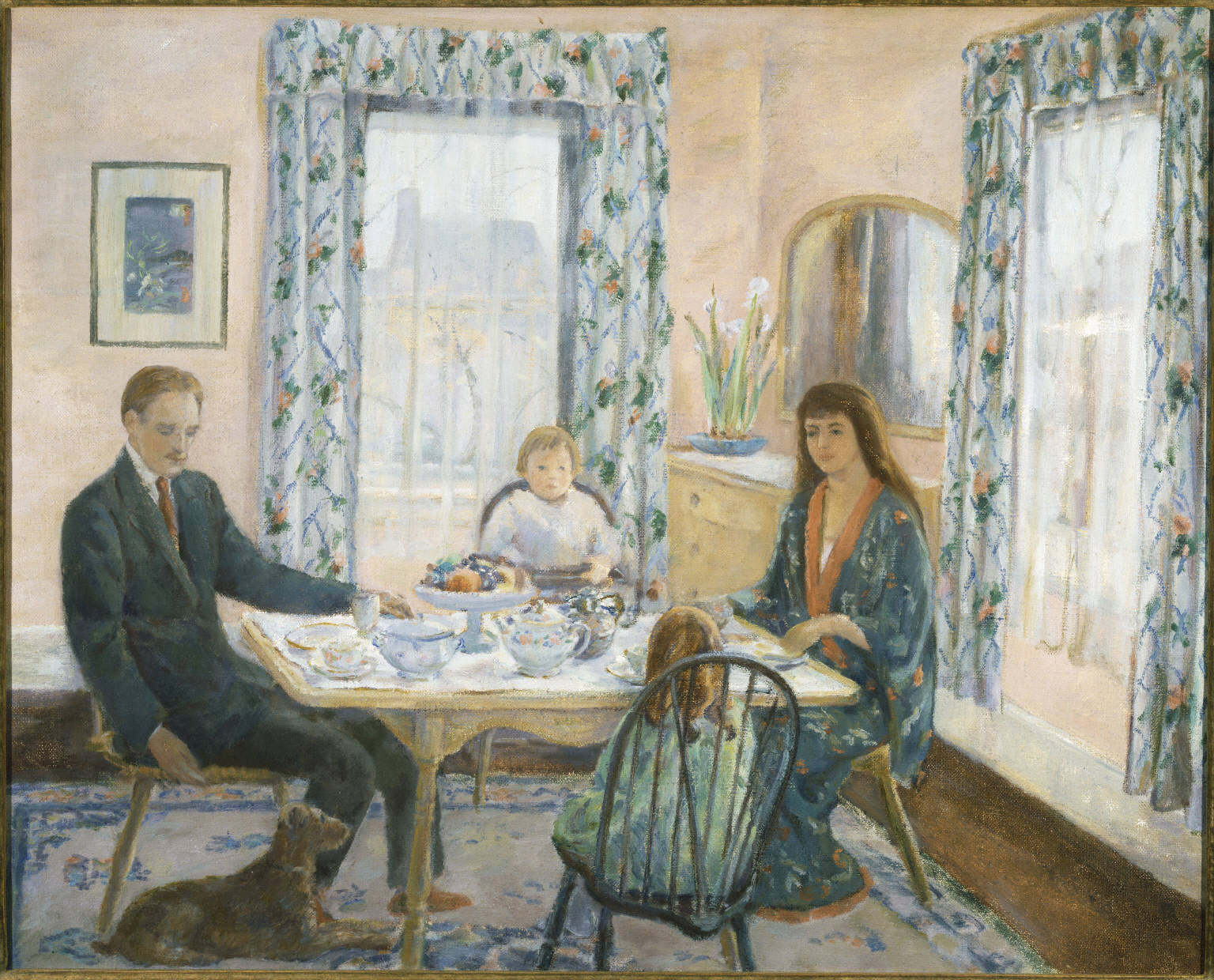

“An artist whose luminous and rhythmical landscapes with figures are worthy to be compared with the works of Berthe Morisot in line and with Andre and Bonnard in color… Although her art is delightfully young, she already reveals qualities we associate with maturity—a tempered flow of spirit and a sensitive but never sentimental transcript of the joy of life into the poetry of design…At the Art Students’ League under Kenneth Hayes Miller there was a touching sincerity in her work and a poise which enabled her to resist the fashionable idols of the hour, Renoir, and Cezanne, in defense of her own individuality. It is even more remarkable that since her marriage in 1921 she has kept her at free from all trace of imitation in spite of the fact that as Associate Director of the Phillips Memorial Gallery she is wholeheartedly responding to many distracting influences.”[1]

If you caught the passing reference to her “marriage” or her role at what was then known as the “Phillips Memorial Gallery,” perhaps you recognized this as a biography of Marjorie Phillips, Duncan’s wife. That Duncan would write so admiringly of his wife—who was one of the few people he would consult about the museum—is not especially shocking. Rather, it seems odd that Duncan writes around his connection to her. In fact, he actively keeps her association with him (and with the museum) at a distance, insisting on her “individuality” and the absence of any “imitation” in her work. It seems, then, that Duncan wanted readers to see Marjorie as talented in her own right, rather than view her success as a product of her circumstances. But, as with many artists—particularly female artists of the early twentieth century—Marjorie’s success was inextricably linked to her privilege.

Though Duncan tries to isolate her biography from her context, the entry does not exist in a vacuum. Specifically, Duncan writes about Marjorie through a gendered lens. As with his other entries on female artists, Duncan argues for Marjorie’s talent by arguing that she has feminine qualities but is not so feminine that her work suffers by it—he also favorably compares her to male artists he admires.[2][3] Marjorie is “delightfully young” but shows signs of “maturity;” she is “sensitive but never sentimental.” He conducts a similar balancing act in his biography of Georgia O’Keeffe, writing that “She can be feminine and dainty, or she can be formal and austere.”[4]

If we wish to understand Marjorie the artist today, we must examine how her gender informed how her contemporaries understood her. In studying how female artists of the early 20th century fared, it becomes clear that Marjorie’s success was unusual.[5] The Phillips Collection featured her work in 16 exhibitions during her lifetime, including a major solo exhibition in 1925.[6][7] The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. included her 1941 painting, Emerging from an Air Raid Shelter, in an exhibition that traveled to the Tate.[8] Another one of Marjorie’s paintings, Bohemian Glass Vase, joined the permanent collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1941.[9]

We cannot understand Marjorie’s success as a female artist without acknowledging her privileges, namely her familial connections to artists and her marriage to Duncan. Here, I have sought to uncover the impact of Marjorie’s privileges without dismissing her merit. Marjorie Phillips had several essential privileges, but these privileges did not ultimately protect her from sexist readings of her work. The aim in this paper is not to praise Duncan for being a supportive husband, nor is it to disregard Marjorie’s skill and work ethic. Instead, I am approaching this topic from the standpoint of lamenting that women depended on such social advantages. In identifying the larger patriarchal structures at play in Marjorie’s story, I hope to make sense of how, a century later, female artists are still at a disadvantage on the basis of their gender.[10] This essay operates from the perspective Linda Nochlin elegantly articulates in her 1971 essay for ARTnews, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” In her words: “The question of women’s equality—in art as in any other realm—devolves not upon the relative benevolence or ill-will of individual men, nor the self-confidence or abjectness of individual women, but rather on the very nature of our institutional structures themselves and the view of reality which they impose on the human beings who are part of them.”[11]

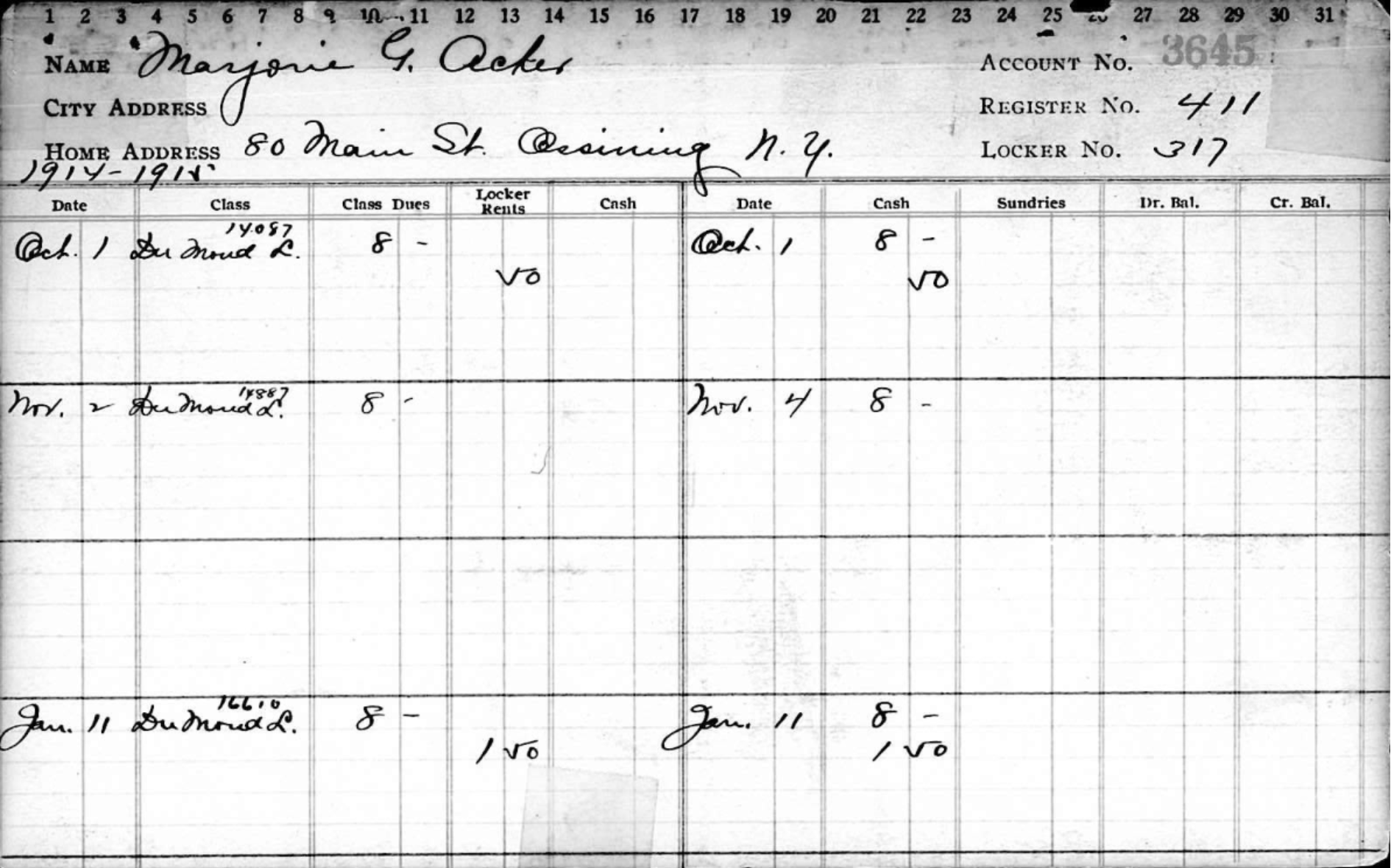

Marjorie Acker Phillips was born in 1894 in Bourbon, Indiana to Charles Ernest Acker and Alice R. Beal. Shortly after she was born, her family moved to Ossining-on-the-Hudson in New York, where Marjorie and her five siblings grew up. Marjorie showed an interest in art from a young age, but her father disapproved. Acker, an electrochemical engineer and inventor, felt that artists were too bohemian.[12] Marjorie found more support in “Uncle Giff” and “Uncle Ren,” the painters Gifford and Reynolds Beal. From 1914-1918, Marjorie and her sister attended the Art Students’ League of New York, where Gifford was president at the time.[13] Years later, Marjorie recalled taking turns commuting into the city with her older sister, Eleanor. In taking turns attending art classes, one elder sister was always available to help their mother with their younger siblings.[14]

Dating at least to the 16th century, there is a consistent pattern of female artists that learned the craft through their close relatives—typically close male relatives.[15] It does not seem that either of Marjorie’s uncles taught her during her time at the Art Students League, nor are they obvious influences on her aesthetic.[16] Yet they enabled her access to formal artistic training, first in persuading her father to allow her to pursue the arts, then in connecting her to an art school where they had power and influence. As a direct result of her family connections, Marjorie circumvented one of the first great institutional barriers for women artist: access to an arts education. Just a few years after concluding her studies at the Art Students League, Marjorie faced another milestone that could obstruct the aspirations of a female artist: marriage.

Marriage could have been a devastating force on Marjorie’s career. As art historian Katy Hessel explains, “women artists were often completely banished from painting or working after they got married.” “Uncle Giff” articulated this danger in a letter to Duncan, dated July 17, 1921. “I have always thought that if she married a man of ordinary vision with no art appreciation she would gradually fade away,” Gifford wrote. “She would stick to her duty but in so doing would dry up and starve artistically. So you can see how pleased I am at the prospect of having you for a nephew.”[17] Gifford walks a fine line between protecting his niece’s ambitions and reifying traditional gender norms. He’d evidently had a persisting anxiety (“I have always thought”) that marriage could lead Marjorie to “gradually fade away.” Yet, on the other hand, he describes the expected responsibilities of a wife as Marjorie’s “duty.” Gifford, one of the most ardent supporters of Marjorie’s artwork, ultimately prioritized her responsibilities as a wife over her career as an artist. It is therefore clear that, if Duncan did not have respect for Marjorie’s intellect and artistic prowess, she would not have had the support from her family in protecting her budding career. It is worth reiterating here that such an observation does not stand to celebrate Duncan, but to highlight the contours of the systemic sexism that led to female artists depending on the “permission” of their husbands.

In addition to the privilege of having a supportive husband, Marjorie had the privilege of wealth. The Phillips family wealth enabled Marjorie to hire domestic help. As American women have historically been disproportionately responsible for household labor, Marjorie undoubtedly particularly benefited from this help.[18][19] With such financial resources, Marjorie had the so-called luxury of time. That her son Laughlin recalls Marjorie making time to work in the studio is primarily a testament to her commitment, it is also a testament to her access to time.[20]

In the end, however, neither familial connections nor an advantageous marriage could fully shield Marjorie Phillips from the challenges of working as a female artist in the 20th century. In the second section of this two-part blog post, I will explore how critical reception to Marjorie’s work illustrates the sexist attitudes she faced as an established artist.

[1] A Collection in the Making, 75.

[2] In the case of Marjorie’s biography, Duncan likens her use of color to that of Bonnard. Given the museum’s extensive Bonnard holdings, this is high praise.

[3] Of the 103 biographies in A Collection in the Making, eight highlight female artists (in order): Berthe Morisot, Emma Ciardi, Helen Turner, Georgia O’Keeffe, Lillian Westcott Hale, Hermine David, Theresa Bernstein, and Marjorie Phillips.

[4] A Collection in the Making, 66.

[5] This essay focuses on Marjorie Phillips’s career as an artist, though she also had a remarkable career as a museum professional. She was the Assistant Director of The Phillips Collection by 1925, and became the museum director upon Duncan Phillips’s death in 1966. Duncan consistently cites her as one of his primary advisors and confidants.

[6] The Phillips Collection Exhibition History.

[7] The Guerilla Girls’ 1988 work, The Advantages Of Being A Woman Artist, is a testament to the exceptional nature of Marjorie’s exhibition history. One advantage: “Knowing your career might pick up after you’re eighty.” See “‘The Advantages Of Being A Woman Artist,’ Guerrilla Girls, 1988.” Tate Website.

[8] Caroline M. Riley, ‘American Painting, 1946’, in Modern American Art at Tate 1945–1980, Tate Research Publication, 2018.

[9] “Bohemian Glass Vase.” The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Website.

[10] For more on the gender inequity in the arts, see The National Museum of Women in the Art’s website page, “Get the Facts.”

[11] Nochlin, Linda. “From 1971: Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” ARTnews.Com (blog), May 30, 2015.

[12] Phillips Family Papers Finding Aid Heinz History Center, 2.

[13] Duncan And Marjorie Phillips and America’s First Museum of Modern Art, Pamela Carter-Birken, 43-44.

[14] Duncan Phillips and His Collection, 3.

[15] Brooklyn Museum Archives. Records of the Department of Public Information. Press releases, 1971 - 1988. 1977, 016-19.

[16] In an interview with journalist Susan Drysdale, Marjorie shared that, though she did not study under either of her uncles, she “probably absorbed a good deal through a sort of osmosis and hearing them talk.” See Pamela Carter-Birken, 43.

[17] Duncan Phillips and His Collection, 14.

[18] Women in heterosexual couples in the United States continue to be the primary people responsible for domestic work. See Brenan, Megan. “Women Still Handle Main Household Tasks in U.S.” Gallup, 2019.

[19] Another reason that domestic help would have been particularly impactful in the Phillips household is that Duncan and Marjorie’s daughter, Mary Marjorie Phillips, was disabled from a young age and lived with the family until the early 1930s. Having a child with Mary Marjorie’s particular disability (encephalitis lethargica) would unquestionably have added to the domestic workload. See Carter-Birken, 12.

[20] Barnes, Bart. “Marjorie Phillips, Artist, Cofounder Of Phillips Collection, Dies at 90.” The Washington Post, June 19, 1985.