Identity in Abstraction

From the Archives

In honor of Black History Month, Digital Archivist Amanda Acosta shares conflicting perspectives on Black American artists working in abstraction.

Abstract Expressionism arose at a point in American history when the cultural scene was ripe with socio-political movements. Instead of visualizing the American climate as it was in the 1950s and 60s, Abstract Expressionists turned inward for inspiration. Artists broke from representational forms in favor of expressive and experimental color application. The movement is primarily recognized through the achievements of white, male painters in New York City. However, Black and women artists like Howardena Pindell, Norman Lewis, Sam Gilliam, and Alma Thomas radically chose abstraction when identity movements called for Social Realism. It has been assumed that Black artists working in abstraction did so “as a personal and professional step toward artistic integration: a step that symbolized their willingness to subordinate Blackness … and to place themselves and their work in a larger, wider, and ultimately, whiter art world” (Powell, p. 102). This assumption negates the self-exploratory nature of the period and reinforces the notion that “other” artists must suppress their identity in order to produce great art. Ultimately these abstract artists did just the opposite, embedding personal motifs, social commentary, and painterly practice into their works.

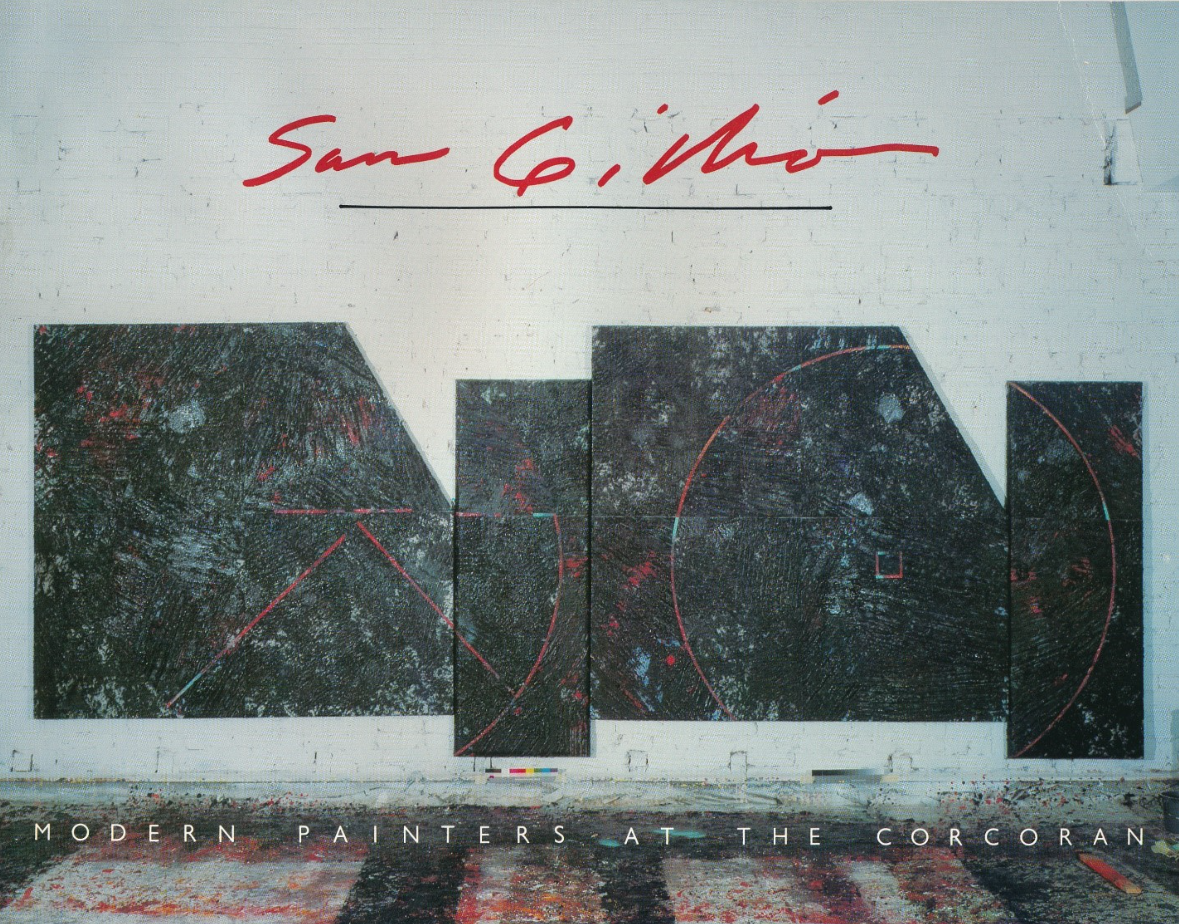

âModern Painters at the Corcoran: Sam Gilliamâ brochure, Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1983. The Phillips Collection Library and Archives, Vertical Files.

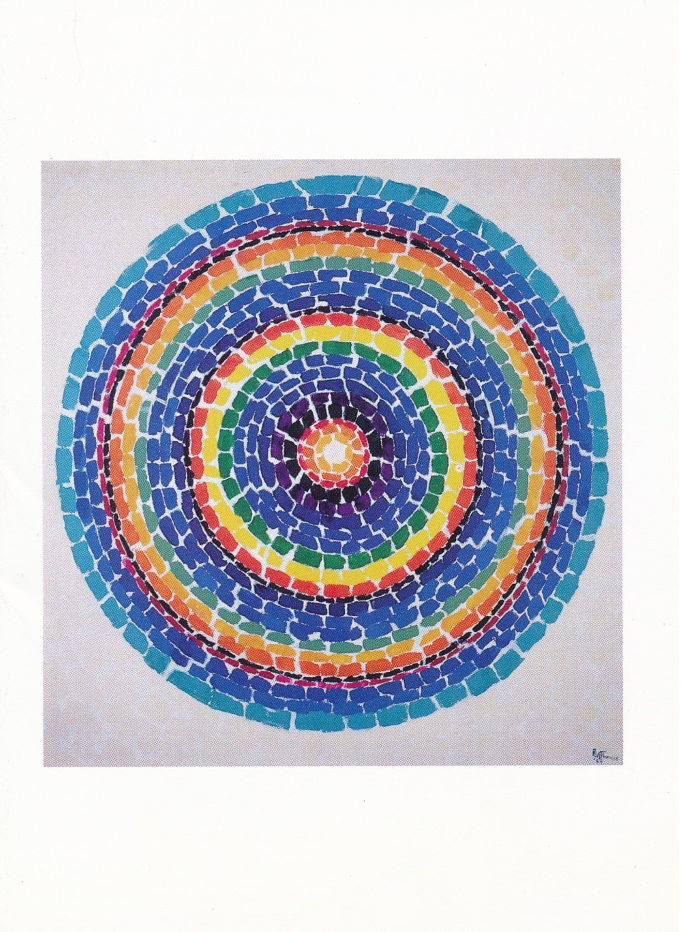

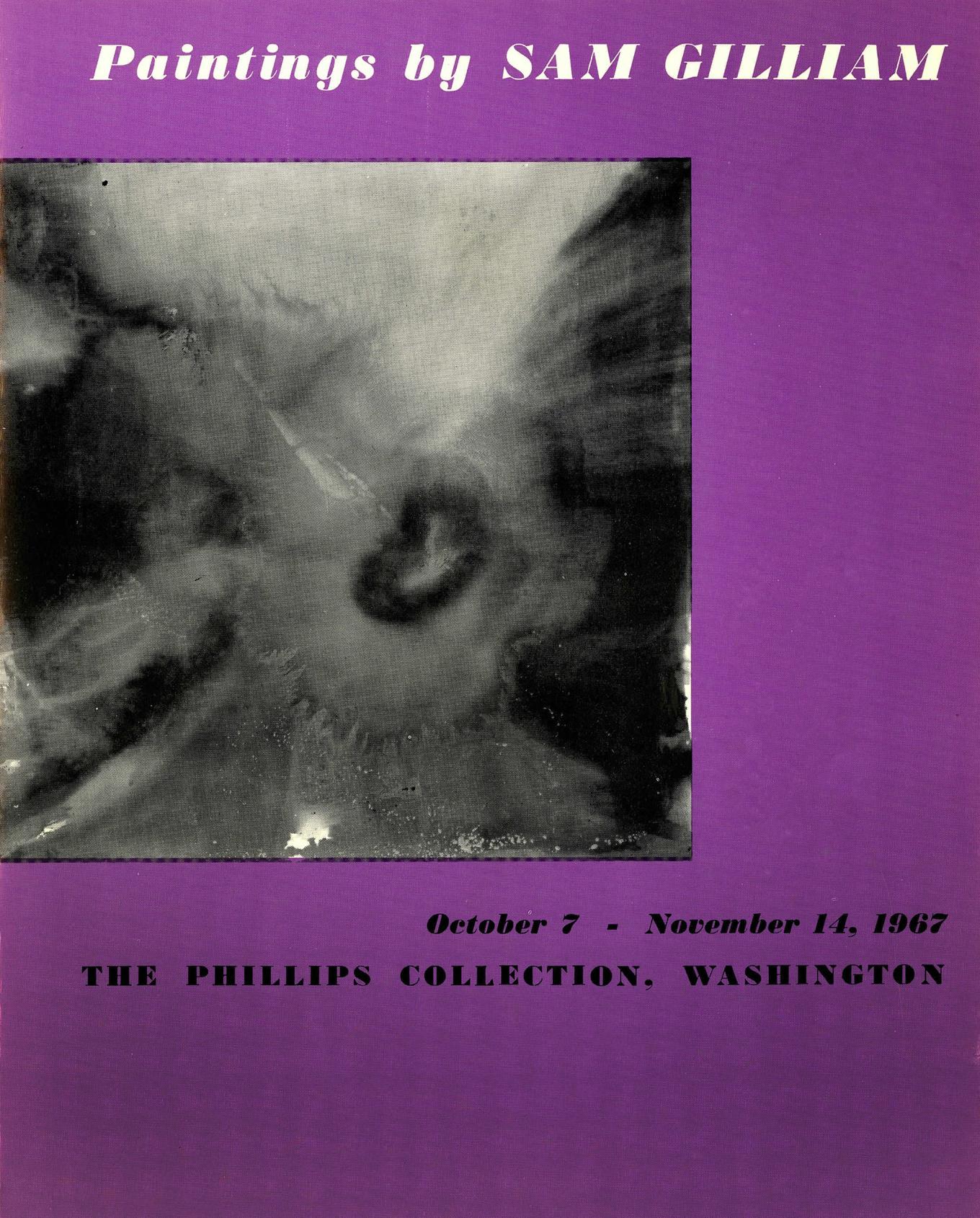

Sam Gilliam and Alma Thomas are among the hundreds of artists for which The Phillips Collection’s library and archives maintains extensive vertical files, with copies of correspondence, exhibition brochures, photographs, and more.

âAlma W. Thomas: A Retrospective of the Paintingsâ membersâ reception invitation, Fort Wayne Museum of Art, 1998. The Phillips Collection Library and Archives, Vertical Files.

âPaintings by Sam Gilliamâ pamphlet, The Phillips Collection, 1967. The Phillips Collection Library and Archives, Exhibition History Files.

Explore the library catalogue and digitized archival materials online. Make an appointment to access our collections by contacting archives@phillipsollection.org. Notes Powell, Richard J. Black Art: A Cultural History. Second ed., Thames & Hudson, 2002