John Marin: A Strong and Bracing Wind

From the Archives

The Phillips Collection is excited to share that the recent publication “Duncan and Marjorie Phillips and America’s First Museum of Modern Art” (Vernon Press, 2021) by Pamela Carter-Birken is now available in paperback. Here is an excerpt from the book focused on the Phillips’s interest in the artwork of American painter John Marin.

Duncan and Marjorie Phillips collected works by John Marin long before Look magazine named him the best painter in America. They would show Marin’s art with works by established European painters, beckoning viewers to the American Modernist. Duncan Phillips regarded the abstract artist from Maine as “one of the most provoking, challenging innovators in the history of painting,”[i] writing that he “blows through the world of modern art like a strong and bracing wind.”[ii] The pursuit of rhythm and a life-long love of the outdoors guided much of Marin’s painting. His own imagination and his ability to engage the imaginations of viewers are key to Marin’s place in art history.

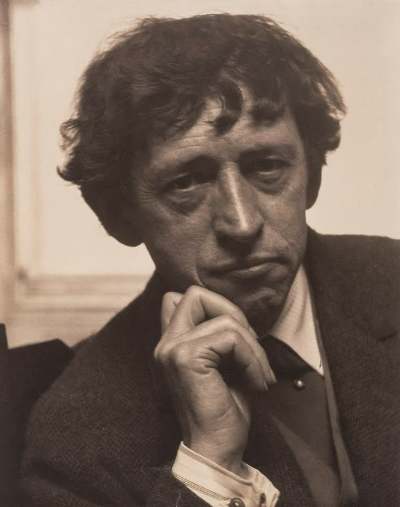

John Marin

Summing up Marin’s biography, Duncan Phillips wrote: “Yankee birth and independence—training as an architect—the influence of Whistler—then of the Chinese, then of Cezanne and Stieglitz—that is the story.”[iii] Marin was almost thirty-years-old when he became a student at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1899. After attending New York’s Art Students League at the dawn of the twentieth century, he lived in France for four years and studied briefly at the Académie Julian. Approaching forty years of age, he moved back to the United States where he would divide his time between New York City and the Maine coastline, the two predominant inspirations for his art. Like his kindred painters of the Stieglitz Circle, Marin did not concern himself with purposeful representation, writing that his works “are meant as constructed expressions of the inner senses, responding to things seen and felt.”[iv] He later added to how he functioned as an artist, writing: “I don’t paint rocks, trees, houses, and all things seen. I paint an inner vision.”[v] Alfred Stieglitz served as Marin’s art dealer, much as he did for other artists of the Circle, including Arthur Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Marsden Hartley. Buying from Stieglitz, the Phillipses would come to own a half-dozen Marin oil paintings, but mostly they bought Marin watercolors. Like Phillips, Hartley admired Marin’s originality as well as his skill. “He paces his strokes to a new beat,” Hartley wrote of his fellow Modernist. “He is keen as a whip, alert as a razor, and has the grip of steel on his medium. Strength is always a personal thing, and this is the case of the mighty Marin.”[vi]

John Marin, Maine Islands, 1922, Opaque and transparent watercolor and charcoal on paper, 16 7/8 x 20 1/8 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1926

Proud of his and Marjorie’s Marin purchases, Duncan sent a letter to Alfred H. Barr Jr. in January 1927 about a forthcoming display of Marin’s works at the Phillips Memorial Gallery. “In February and March I will give Washington a bracing shock in the work of this stimulating creator,” Phillips wrote to the future MoMA director, describing Marin “with his incisive brain, his flashing eye, his startling intuition and magic with his medium.”[vii] In highlighting works by Marin in the winter of 1927, Phillips blazed the trail for New York City’s Museum of Modern Art, still two years from its opening. It would take ten years after Phillips’s boast for Barr to present a Marin retrospective at MoMA, the first for an American artist there. Phillips, however, did not wait a decade to broaden potential appreciation for Marin. He reached an international readership with an assessment of Marin’s importance in his 1932 article about American art for the journal Formes, published in French and English. “Never safe and sane,” Phillips wrote of Marin’s paintings, “with details often askew and out of focus, but with the essential part intensified and magnetic.”[viii] The following year, 1933, New York Times art columnist Edward Alden Jewell called Marin “an American artist of genius.”[ix]

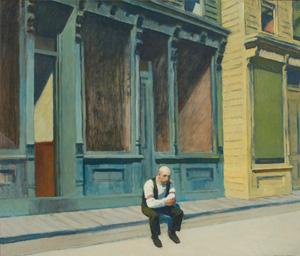

Edward Hopper, Sunday, 1926, The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1926

About the same time, art critic Lewis Mumford wrote a remarkable essay for the New Yorker which can supply context for the multitudes of accolades Marin amassed. Mumford contrasted the act of viewing works by Marin to those painted by Edward Hopper, famous for restaurant and theater slices of life, sometimes featuring men with fedoras and women in fashionable coche hats, and almost always conveying a struggle to cope with modernity. Hopper’s best-known work is Night Hawks, which hangs in a place of pride at the Art Institute of Chicago. The iconic Night Hawks was not painted until 1942, but Phillips had purchased another Hopper, an imposing oil-on-canvas titled Sunday in 1926, the year the artist created it. In Sunday, the scene is barren save for disturbingly hued building fronts and a lone man sitting on the edge of a wood sidewalk, his feet planted in the street. It is a stunning work of art and will compel all but the most jaded visitors to stop and ask the questions who, what, when, where and why. In the New Yorker essay, titled “Two Americans,” when Mumford praises Marin at the expense of Hopper it is high praise indeed. “Visually speaking,” Mumford wrote, “one may follow Hopper on the pedestrian level; following Marin, one must risk one’s neck in an airplane.”[x] Mumford offered an additional opinion on the impact works by the two artists might have on viewers: “Both Marin and Hopper have been interpreters of America, but while Hopper has utilized our limitations and made the most of them, Marin has demonstrated our possibilities.”[xi]

[i] Duncan Phillips, A Bulletin of The Phillips Collection, Phillips Memorial Gallery, Washington, 1927.

[ii] D. Phillips, “Trowbridge Memorial Lecture: The Artist Sees Differently,” (Yale University, March 20, 1931), The Phillips Collection Archives, Washington, D.C., 12.

[iii] D. Phillips, A Bulletin of The Phillips Collection, 1927.

[iv] John Marin, The Forum Exhibition of Modern American Painters (New York: Anderson Galleries, 1916).

[v] Marin, “Letter to Stieglitz, Written in 1923,” Philadelphia Museum Bulletin, XL (1945).

[vi] Marsden Hartley, “As to John Marin and His Ideas,” John Marin: Watercolors, Oil Paintings, Etchings (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1936), 18.

[vii] D. Phillips to Alfred Barr, Jr., 15 January 1927, The Phillips Collection Archives, Washington, D.C.

[viii] D. Phillips, “Original American Painting of Today,” Formes, January 1932, 198.

[ix] Edward Alden Jewell, “The Rise of John Marin,” New York Times, October 23, 1933.

[x] Lewis Mumford, Mumford on Modern Art in the 1930s, ed. Robert Wojtowicz (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 101.

[xi] Ibid.