Marjorie Phillips: Artist and Executive

From the Archives

The Phillips Collection is excited to share the recent publication of “Duncan and Marjorie Phillips and America’s First Museum of Modern Art” (Vernon Press, 2021) by Pamela Carter-Birken. Here is an excerpt from the book, which reveals the stories of the people who worked to make The Phillips Collection both an experience and a home.

The Phillips Collection is excited to share the recent publication of “Duncan and Marjorie Phillips and America’s First Museum of Modern Art” (Vernon Press, 2021) by Pamela Carter-Birken. Here is an excerpt from the book, which reveals the stories of the people who worked to make The Phillips Collection both an experience and a home.

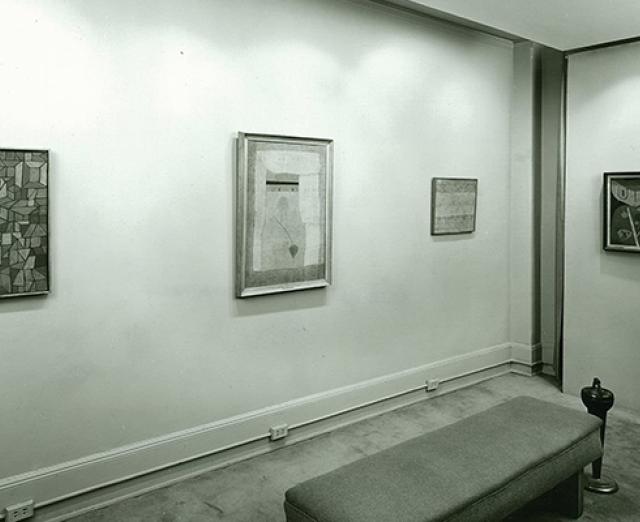

The Gilded Age had waned when Marjorie Acker attended the Art Students League of New York. She took the train into the city from Ossining, New York, where she lived with her parents and six siblings. Her routine was to disembark at Grand Central Station on 42nd Street then walk up Fifth Avenue to reach the renowned art school on 57th Street. The Indiana-born painter loved New York City. She would pop into art galleries to see the latest works on display whenever time allowed. … Please don’t disturb read the sign Marjorie put on the door to her studio, a dedicated space first located within the Phillips’s Dupont Circle property and later at their Foxhall Road home. She had always been a disciplined creator, even painting on her honeymoon. The newlyweds’ get-away would not be the only time she packed palette and easel. During her years with Duncan, she made the most of their summers in the Alleghenies. “It was a wonderful place for painting,” she said of rural Ebensburg, Pennsylvania. “Social life didn’t follow you there. You could walk, paint. I’d work in my studio, from the car or in a field on the spot.” Back in Washington, Marjorie set aside mornings for painting. On those afternoons when she was tempted to return to a work-in-progress, the duties of being a museum executive usually prevented her from opening the studio door again until the next day. While Marjorie did not become director of The Phillips Collection until after Duncan’s death in 1966, she served as its associate director for 41 years and bore responsibility for the minutiae of organizing temporary exhibitions in the museum’s Prints and Drawings Room. …

Marjorie Phillips, Self-Portrait, c. 1940, Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 16 1/2 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of the artist, 1985

No matter the task at hand, Marjorie saw the world as an artist. Duncan admired her for it, and throughout her career he cheered her on. In 1948, Duncan composed the foreword for an exhibition brochure about works by Marjorie. The exhibit was first mounted at the Bignou Gallery and then shown at the Phillips Gallery. In his description of her art, Duncan wrote: “What we need today is not just another group movement but a few individuals who love that real light, which is the life of everything it touches. Such an artist is Marjorie Phillips who, in spite of keen understanding and appreciation of many [artistic] techniques is never distracted from her course. She is a luminist with a truly classic feeling for composition of pictorial space.” In the context of art history, Luminism was a term coined a half-dozen years after Duncan wrote the foreword. It referred to a group of artists who could use light to turn sky or sea ethereal. With pervading light came a feeling for the universality of nature. As an art movement, Luminism encompassed painters in the 19th century’s Hudson River School, among them Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt. Marjorie would have been familiar with Church’s interpretation of Niagara Falls and Bierstadt’s of the Rocky Mountains, among other sweeping renditions. When Duncan called Marjorie a luminist he was not comparing her to the great American landscape artists. Rather, he was referring to how she used light to enhance what he saw as her individualism.