Legendary Cinematographer Karl Struss's Visit to the Phillips

From the Archives

Colleen Hennessey, Archives Assistant, on Karl Struss’s visit to the Phillips and his impact on film and photography.

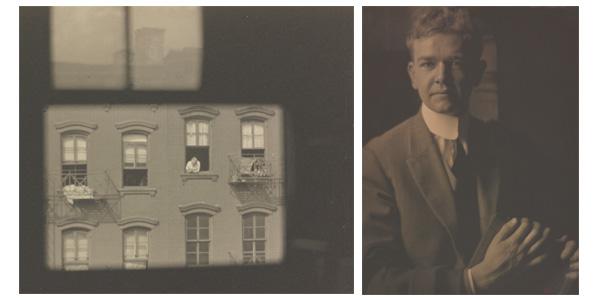

(left) Karl Struss, The Open Window, ca. 1910-1911. Platinum print, 3 11/16 x 4 5/16 in. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas © 1983 Amon Carter Museum of American Art (right) Clarence H. White, Portrait of Karl Struss N. Y., 1912. Platinum print, 9 1/4 x 7 in. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

When the red carpet rolled out this year for Tinsel Town’s big night, film fans around the world tuned in to watch the 87th annual Academy Awards. This event reminded me of something I recently ran across at The Phillips Collection, where I work in the museum’s library and archives. In 1977, Oscar-winning cinematographer Karl Struss (1886-1981) and his wife Ethel were in Washington for an exhibition of his photographs at the Phillips—Karl Struss: Man with a Camera.

Struss was a youthful 91 at the time, tall, distinguished with thick white hair, engaging and sharp of wit by accounts, and then the lone surviving member of Alfred Stieglitz’s Photo-Secession group. His career as a pictorial photographer began in 1908, when he studied photography with Clarence H. White. White’s studio, which Struss took over in 1914, was located across the street from Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery, and it was White who likely introduced Struss to Stieglitz. At the age of 25, Karl Struss was one of the youngest and also the last artist to become a member of Stieglitz’s prestigious inner circle. Stieglitz championed his work, giving him a wall to himself in the Photo-Secession’s legendary 1910 Albright Gallery exhibition in Buffalo, and selecting six of his images for printing in the April 1912 issue of Camera Work. Struss also helped to form the 1913 journal Platinum Print, and together with Clarence White and Edward Dickson founded the Pictorial Photographers of America in 1916.

Stunning Whistler-esque views and modernist compositions have made Struss one of the great early photographers of New York City—his birthplace. Recognition as one of Hollywood’s most renowned cinematographers came after he moved to Los Angeles in 1919, where almost immediately he was hired by producer-director Cecil B. DeMille, first as a still photographer to make publicity shots of the stars and soon thereafter as a cameraman. Earlier in his career, Struss had devised his own single element lens, a soft-focus lens that he utilized to great advantage in making a bevy of the stars look beautiful, among them Claudette Colbert, Mary Pickford, Gloria Swanson, and Mae West, who was so appreciative of how his photographs made her look that she rewarded him with a large diamond ring. It was in Hollywood that Struss met and married Ethel in 1921, a printmaker. When Louis B. Mayer, head of MGM, gathered up a group of 36 people involved in the film industry for a formal banquet in 1927, Struss was among the invitees who would go on to found the Academy of Motion Pictures and Sciences.

One of the first to work in color and a pioneer of 3-D films, his career as a cinematographer spanned over 51 years of work on 120 films. Known to cinema fans for his work on Ben-Hur (1925), Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940) and Limelight (1952), among many others, Struss was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Cinematography four times. The first and only time he won was with co-photographer Charles Rosher for F. W. Murnau’s Sunrise (1927) at the very first Academy Awards ceremony in 1929, where the film also won what is now the Best Picture award. Sunrise was German director Murnau’s American debut, done for Hollywood’s Fox Film Corporation. Produced at the end of the silent-film era, it was the first feature film that used the Fox Movietone system in which the public heard synchronized sound-on-film (music and sound effects only).

A fable-like, poetic film subtitled A Song of Two Humans, Sunrise is a melodramatic masterpiece—a classic love story of corruption and redemption involving a farmer who falls prey to the seductive wiles of a city vamp in an illicit affair. This beautiful, atmospheric work of art with roots in German Expressionism (Murnau’s best known work was the 1922 film Nosferatu) was exquisitely visualized and sensually photographed using breakthrough camera tracking movements that would influence future films. Overshadowed by a career in Hollywood, his other contributions had been largely ignored until the mid-1970s, when film historians John and Susan Harvith visited Struss at his California home and discovered his still photographs. They authored a catalog and organized an exhibition of his work that premiered at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan before traveling to the Phillips and other venues. The 1970s was still a time when few museums were willing to exhibit photographs, especially by someone largely unknown at the time, and this was only the second one-man show of his works since 1912.

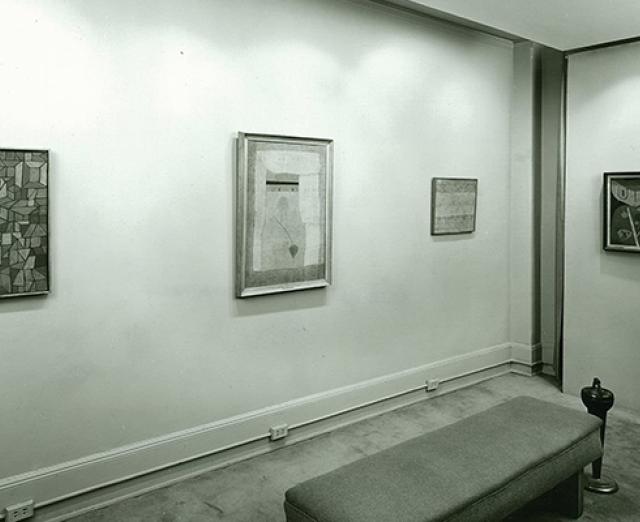

Over ninety original photographs of Struss’s work done between 1908 and the 1930s were exhibited at the Phillips in 1977, when the show was extended for two weeks due to popular demand. One of the joys of my job as an archivist is the delight of accidental discoveries―in this case, learning about Karl Struss. The Phillips Collection archives house records of the exhibition and other related documentation in the files of former Phillips staff members. I was startled to first notice a letter written in 1977 to Struss by then Assistant Curator Kevin Grogan, acknowledging that 34 photographic prints from the original negative of the film Sunrise were being held temporarily at the Phillips until release to the American Film Institute. Karl Struss’s name was new to me, but I had seen Murnau’s landmark film Sunrise several times, and the thought of such prints having been held at the museum seemed thrilling to me. Letters attested to the gracious nature of Karl and Ethel during their visit that year, and numerous clippings discussed his career at length.

Today, his prints are in various public collections, among them the Amon Carter Museum of American Art which owns a sizable number of his early photographs and where his personal papers reside in their archives. Struss came to Hollywood with the idea that his knowledge of lighting and composition might influence the aesthetics of movie-making at a time when operators sometimes did little more than crank a camera, and there he worked his magic at the intersection of still photography and moving pictures.