Afrofuturism 101

Education & Community Engagement

The Phillips Collection Fellow Arianna Adade on Afrofuturism as an art movement and beyond.

In March, I met with Digital Intersection artist Joel Crooms, who calls himself an Afrofuturist. Several artists in the upcoming exhibition Multiplicity: Blackness in Contemporary American Collage are also inspired by Afrofuturism. Last fall, the Phillips partnered with Afropunk, which celebrates all things Afrofuturism. For many, such as myself, Afrofuturism allows one to deeply connect with their heritage and honor it in a contemporary world. It fosters solidarity for Black individuals across the globe, allowing for Black contributions to be uplifted. So…what is Afrofuturism?

Flying cars, space colonies, interstellar realities. These are just some of the many components that make up Afrofuturism. Having emerged in the late 20th century, Afrofuturism combines elements of science fiction, African mythologies, imagination, and sociopolitical liberation. In a nutshell, it reimagines the Black experience and identity, exploring what a new future could be for the Diaspora.

Afrofuturism was coined by Mark Dery in 1993 in his essay, “Black to the Future,” as a way to define the exploration of Black literature and technoculture. Even before the official coin of the term, many often questioned the exclusion of Black identities in the world of science fiction and other explorative genres, given the technological developments that originated throughout history in the African continent. Early visionaries implanted the roots of Afrofuturism through blending African heritage with future aspirations. Sun Ra, a jazz visionary whose work in the 1950s and 1960s further pushed Afrofuturist values, was one of the pioneers and often seen as the most influential of the movement.

Sun Ra, Photo courtesy of the National Museum of African American History and Culture

The effects of the transatlantic slave trade had a tremendous impact on Afrofuturist concepts. Forced dehumanization and cultural erasure experienced by Africans during the slave trade resulted in a fundamental fracture that Afrofuturism strives to address and restore. The movement reclaims this history by envisioning futures in which Black people are characterized not by oppression, but by independence, creativity, and resilience.

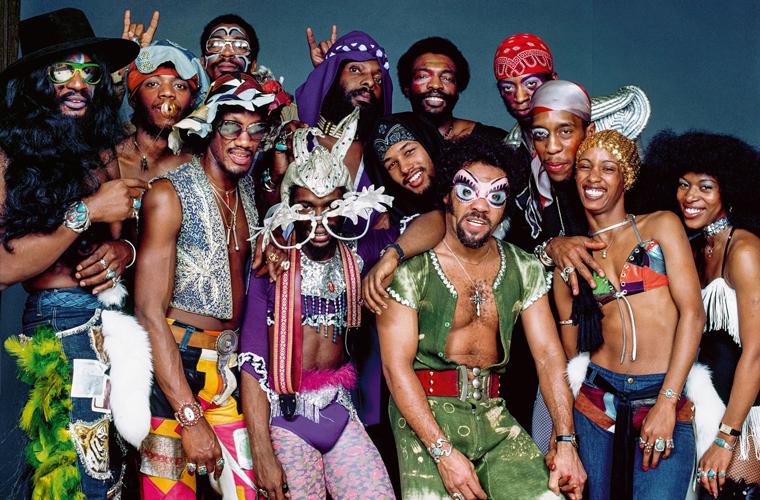

George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic contributed to popularizing Afrofuturism in the 1970s. Their P-Funk mythos, reflected in records such as “Mothership Connection,” comprised of space-themed arcs and futuristic attire that symbolized galactic independence. This fusion of music and visual art captivated audiences’ imaginations and reinforced Afrofuturist concepts in popular culture.

George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic, photographed at the Los Angeles Sports Arena, 1977. Photo: Bruce W. Talamon, 2018

In the 1980s, Jean-Michel Basquiat used African iconography and modern urban graffiti in his paintings to explore topics of race and identity through a futuristic vision. His art exemplified Afrofuturist ideals by questioning conventional narratives and proclaiming Black identity through his original combination of Afrofuturism and 80s/90s hip-hop aesthetics. Basquiat’s uniqueness expanded the space for Afrofuturism in the art world.

Wangechi Mutu, Riding Death in My Sleep, 2002, ink collage on paper, 60 x 44 inches. Collection of Peter Norton, New York

Wangechi Mutu (whose work is featured in Multiplicity) is another artist who embodies Afrofuturism in art. The Kenyan-born artist produces intricate collages, sculptures, and installations that frequently incorporate hybridized figures—part human, mechanical, and animal—that explore issues of identity, gender, and post-colonialism. Her artwork creates alternative futures in which African identities are integral and powerful. Performance art, fashion, and literature also expanded Afrofuturism’s range. Grace Jones’s androgynous, futuristic appearance, as well as her collaborations with visual artists, contributed to the popularization of Afrofuturist aesthetics. Octavia Butler, known as the “Mother of Afrofuturism,” built her own worlds and realities in science fiction that neglected Black identities. Her works not only expanded science fiction, but are considered the earliest literary writings of Afrofuturism. Through bold, avant-garde expressions in many artistic forms, these artists lay the framework for Afrofuturism’s continuous expansion and impact.

Afrofuturism has had an enormous rebirth in contemporary culture, thanks to a rekindled dedication to analyzing Black identity and culture through futuristic and visionary lenses. This rebirth has been motivated by the success of mainstream media, such as Marvel’s Black Panther (2018), which exposed Afrofuturist visuals and aspects to a universal audience. Individuals all over the globe were captivated by the film’s depiction of Wakanda, a highly technologically sophisticated African nation, which portrayed a vision of African wealth and innovation free from colonialism.

This return mirrors a wider cultural movement of reclaiming and honoring African ancestry, as well as challenging and restructuring future narratives. Today, Afrofuturism is more than simply an artistic movement. It is a powerful instrument for progressing social and political rights, strengthening community, and conceiving a future of liberation for the Black diaspora.