The Phillips Collects: Marta Pérez García

Collection

2021-22 Sherman Fairchild Fellow Shiloah Coley speaks with Inside Outside, Upside Down artist Marta Pérez García, whose work Your Hand has been acquired by the museum.

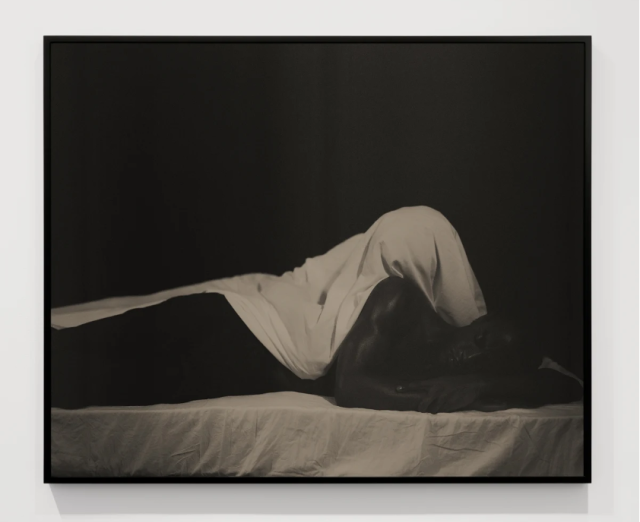

Marta Parez Garcia, Your Hand, 2020, Molded cotton handmade paper and stitching with yarn, 19 x 11 x 2 in., Courtesy of the artist

Tu mano Tu mano,/ La misma que una vez me acaricio / Ahora me arrebato la vida. Your Hand Your Hand,/ The very one that once caressed me / Has now taken my life. This is the poem that is stitched across the top of Marta Pérez García’s Your Hand. The work begins to break the boundary between 2D and 3D as the vibrantly colored stitched hand emerges off of the molded cotton handmade paper. “This is who we are. This is our temple. This is where we suffer, where we laugh,” said Pérez García in reference to the significance of a woman’s body. “This is who we are, and when I created the piece now in The Phillips Collection, I thought about the hand, and how the hand becomes a weapon. At the same time, it is something that caresses, that helps people.” Domestic violence has been referred to as the “shadow pandemic” by UN Women. While many found comfort in their homes when directed to shelter in place due to the outbreak of covid-19, the reality for many was that the closing of schools and services (where mandated reporters are often found), paired with family isolation and additional stresses from the pandemic, created the perfect storm for domestic violence. Pérez García has worked with survivors on projects tackling gender violence as a central part of her practice. During the pandemic, she realized sheltering in place did not offer the safety it implied for survivors who would be left stranded with their abusers. The CDC even warned that more time spent in the home would likely increase the risk for child abuse, domestic abuse, and intimate partner violence with less opportunities for victims and survivors to seek outside services or shelters. “For me it was very important to put this piece out there so people reflect and understand what it means for these women to be home right now,” Pérez Garcia says. Fellow Inside Outside, Upside Down artist Aaron Maier-Carretero also addressed this in his work recently acquired by the Phillips, not in front of the kids. When contemplating which medium was best-suited for working with survivors, she shifted from her usual printmaking process to needle and yarn, remembering the lessons her grandmothers tried to teach her as a child in Puerto Rico. “I always thought, ‘I’m too hyper to do this!’,” shared Pérez García. “I remember one time Mama Loísa sat me down and gave me the stuff, and I thought, ‘I can’t do this. This is too meditative.’” As she began to teach herself how to sew again, she found that the action of sewing didn’t relax her, but made her think: “I was reflecting about the lives of these women, then I was reflecting about my own life.” The sewing connected her own story to the stories of the women she worked with. “You realize that when you sew, you create a story. You talk and you’re sitting down with other people. It’s a space for you to really give a life to your stories.” Sewing is a tradition that crosses many cultures. In the context of Latin America and the Caribbean, sewing is a craft and task often assigned to women as it has historically been viewed as “women’s work.” However, Pérez García’s work subverts that traditional view—what if sewing is an opportunity for liberation and the connection of our stories? a way for marginalized women across all communities to make their own freedom? “People have to reflect and think about these women,” said Pérez García.