The Phillips Collects: Nekisha Durrett

Collection

2021-22 Sherman Fairchild Fellow Shiloah Coley speaks with Nekisha Durrett about the recent acquisition of her work from the juried invitational Inside Outside, Upside Down.

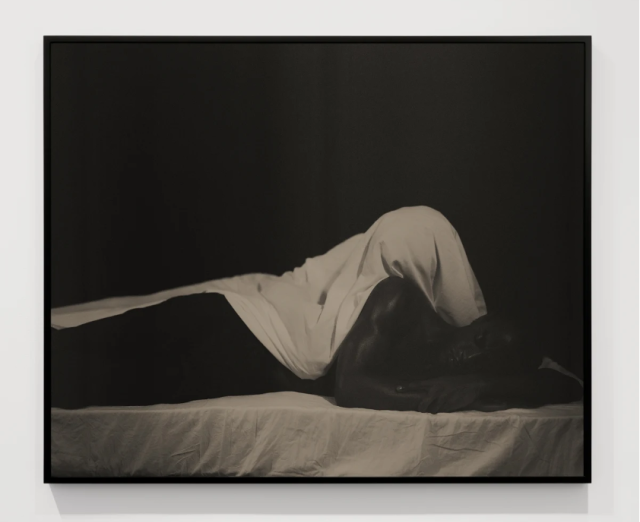

Nekisha Durrett, Eleanor Bumper killed by police on October 29, 1984 | Age 66, 2020-21, Magnolia leaves, poplar, velvet, acrylic, LED lighting, 19 1/4 x 19 1/4 x 5 3/4 in.. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Luke Walter Photography

Nekisha Durrett always knew she wanted to be an artist, and her chance encounter with Jacob Lawrence at The Phillips Collection made it seem a little more attainable. He was one of the first examples of a Black person she saw operating in that space, making a life as an artist. “You know that you want to be an artist, but you don’t see anyone else like you or in your family doing it. You’re not seeing people who look like you who are doing it and are successful in the ways that you see white artists—white male artists are successful,” said Durrett. “There is no roadmap. Everyone’s pathway is very different. Add on top of that not seeing any representation of anyone who looks like you who’s making a life of it. So in that regard, meeting Jacob Lawrence, seeing his work hanging in the museum, I think it probably became more of a maybe. It did feel just a little a bit more in reach.” Her work from Inside Outside, Upside Down now joins the permanent collection at the Phillips alongside Lawrence’s work. Eleanor Bumper killed by police on October 29, 1984 | Age 66 honors the life of a Black woman killed by the police. The magnolia leaf dawns her carved-out name. While the magnolia tree is popular for its beautiful flowers, its leaves stand the test of time, refusing to decay or wither. The work is part of a larger series, Magnolia, honoring many Black women. “I always see the outpouring of emotion or attention when Black men were murdered, and I felt like it wasn’t the same for Black women,” Durrett said, recalling her thought process behind the work. The delicate pieces differ from the larger public pieces and projects she typically takes on, but she couldn’t work on those to the same extent amid the pandemic. During the spring and summer of 2020, Durrett collected the fallen leaves from a magnolia tree in Rock Creek Cemetery, where she would go to process her anxiety and grief over the covid-19 pandemic and the continued police brutality against Black bodies. Noting the immense amount of videos and images of violence against Black people circulating, the leaf emerged as a useful metaphor. “I didn’t want to put that kind of labor on Black bodies so using this leaf as a metaphor for the Black body just seems to make sense,” Durrett said. This work is intimate, demanding the viewer’s attention if they are to truly see it, asking them to get closer. Similar to how Lawrence helped open the door for Durrett, she now continues that legacy with her audience. Her therapist, who is located around the corner from the Phillips, visited the museum to see her work, sharing that she’d never been before and didn’t think it was a space where she would see herself, a feeling far too familiar for marginalized folks, and especially Black folks in museum settings. “That is a part of the work. It’s creating a space where you can see yourself,” said Durrett.