How Nekisha Durrett's Airshaft turns the everyday sacred

Collection

2021-22 Sherman Fairchild Fellow Shiloah Coley speaks with Nekisha Durrett about her centennial commission, Airshaft.

Nekisha Durrett stands in front of her centennial commission installation Airshaft

“Whenever I come to The Phillips Collection, I think about the first time I came here,” said Nekisha Durrett as she walked me through her initial proposal for her centennial commission Airshaft. The immersive installation converts the two bridges joining the Goh Annex and the original Phillips House into a sacred place as light floods through the large windows, changing to different colors as they pass through the colored film giving the effect of stained glass in patterned geometric shapes lining the nearly floor to ceiling windows. In high school, one of Durrett’s dear friends invited her to tag along after school to an event at the Phillips. Without knowing the details, Durrett agreed. As she walks through the front door, an older gentleman greeted the then teenagers. She shook his hand. The event was a book signing for Jacob Lawrence’s Great Migration catalogue. She had learned about Jacob Lawrence in school, and shook his hand. “When I came to visit all of the proposed sites for the centennial commissions, that memory was always running through my mind,” Durrett said. “Every time I come to the Phillips, I think about this. So I was like, why not make this central to the piece? You know, why not create a piece that springs from that memory?”

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel 31: The migrants found improved housing when they arrived north., 1940-41, Casein tempura on hardboard, 12 x 16 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1942

Jacob Lawrence’s Panel 31 in The Migration Series inspired the designs on the windows. His work depicts the outside of a Harlem tenement where so many Black newcomers from the South settled into their new lives. The airshafts in these buildings captured all the most intimate and mundanely routine moments of life. Smells and sounds permeated through the vents and the building, transporting intimate moments in the households as whispers for others to catch. The tenements were full of life and the airshafts captured that life. “I think all your life people tell you what’s supposed to be sacred,” Durrett shared as she considered the sacrality of the bridges. The stained glass effect her work has is reminiscent of what some of us are accustomed to seeing on the windows of churches and cathedrals. But it’s not the sacredness of religion that Durrett is concerned with. She is concerned with the sacredness of those tenements and the lives we live. “To make something sacred in this regard is sort of this revolutionary act where you’re saying, no, I’m sacred. I create my sacred space. My people, my family, the space that we build together is also sacred. Everyday life is sacred,” said Durrett. Just like the everyday lives celebrated in Lawrence’s work.

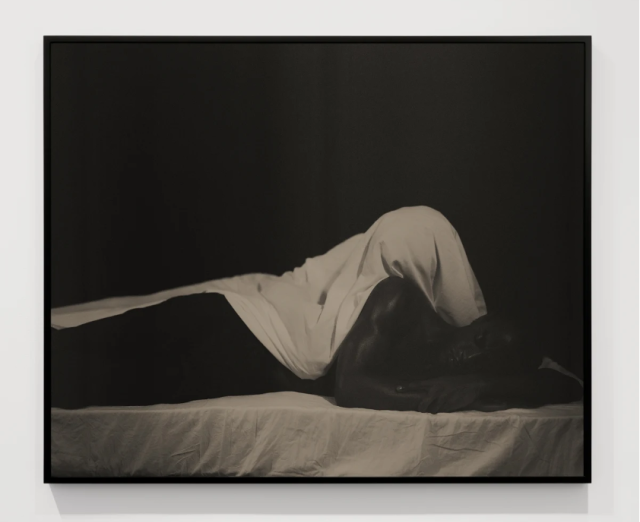

Nekisha Durrett, Airshaft, 2021