The Phillips Collects: In Conversation with Oren Eliav (Part I)

Collection

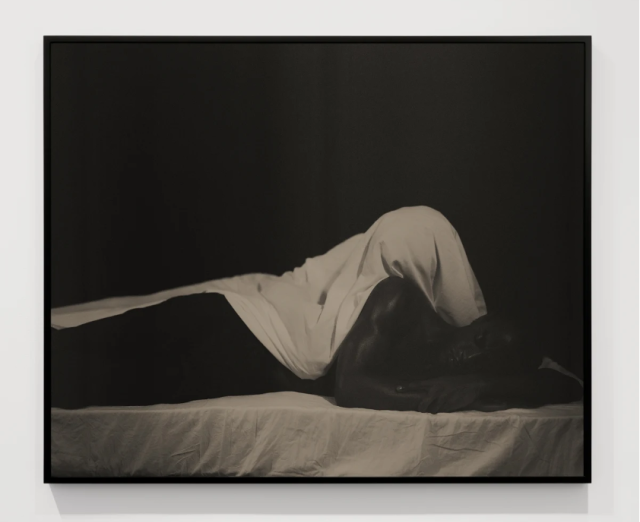

Sherman Fairchild Fellow Ariana Kaye visited the studio of Oren Eliav in Tel Aviv Israel. Eliav’s Listener, 2012, was recently acquired by The Phillips Collection, and is featured in the major centennial exhibition Seeing Differently: The Phillips Collects for a New Century.

Ariana Kaye: First off, thank you for having me here at the studio. It’s such an honor. I love the new works. Did you know your work was in The Phillips Collection?

Oren Eliav: Thank you for coming, Ariana. I was gladly surprised when you told me they hung the work, it’s an honor.

Outside of Oren Eliav's studio in Tel Aviv. Photo: Shira Linde

AK: This year is the Phillips’s Centennial year, their 100th year, their birthday, and your painting is in the Centennial exhibition! I was talking to the staff, and told them I love this work and the artist—maybe I can reach out to him and they said of course. So I emailed you and this worked out so well. Do you know how the work got to be there?

OE: It is thanks to a long-time collector, Tony Podesta, who was introduced to my work by my gallerists at Braverman Gallery. He has been following my work since the beginning, and he generously gifted the work to The Phillips Collection.

AK: Can you share a sneak peak of what you have been working on recently?

OE: I haven’t spoken to anyone about this yet. It’s really fresh and different from my last two shows, which were carefully planned as a whole choreography of paintings for a space. How to Disappear Completely was a large-scale installation for the Israel Museum, and Mount Zero was a four-floor journey at Building Gallery, Milan. This time is a bit different.

AK: I read extensively about it, it was amazing!

OE: I am used to engaging in a long process of planning, modeling, thinking, and writing. This time I’m going about it in a simpler manner, which means just painting daily in the studio, seeing what comes and letting it unfold. It is starting to come together and will revolve around the notion of echo location or sonar. It will be held at Braverman Gallery, Tel Aviv, in January 2022.

AK: That last exhibition, Mount Zero, seemed ambitious and different.

OE: It was a landmark exhibition for me. It took place in Milan, the epicenter of the pandemic at the time. We had to make tough choices whether to postpone the exhibition or not, but in the end, I decided to go through with it. I felt that since it was already three years in the making, including a book, that the time has come and that the show must go on, as they say.

AK: Your use of art historical imagery from Christianity is meant to disrupt ways in which we see and understand the world. However, one cannot ignore direct references to religion in your work, as some of the source images come from Church or papal commissions. How do you view religion and how does it influence your artistic practice?

OE: It’s going to be a long answer…

AK: I’m here to hear it.

Ariane Kaye and Oren Eliav in conversation. Photo: Shira Linde

OE: Let’s start by saying that personally I’m an atheist, an absolute atheist. Religion is a strong organizing idea. It used to be a satisfying system to explain the world and its mysteries. But eventually, with the advent of science, we now have better explanations. It was also an organizing system for our societies, and it helps many individuals make sense of their lives, I guess. But religion in a way diverts us from the real magic—the fact that we are an organic material arranged in such a way that it is not only able to come to life but also to be aware of it. We have a brief period of time to appreciate this, to be conscious of our one life. So, I see no point in thinking that something more precious will reveal itself in some sort of heaven or an imaginary afterlife. As to your question, I used to work with other paintings as my starting point. It’s not the roofs of Tel Aviv or my childhood memories that are my primary sources of inspiration, its art coming from other art. And as it happens, painting from the past is steeped in religious imagery, namely Christianity. So, it was part of the package and I decided to look at it attentively and observe the various visual mechanisms that are at work, for example when looking at an altarpiece or a cathedral.

AK: Even tells you how to see them.

OE: In my new work I’m starting to move away from that, but the basic question remains the same: what is it that we really see? and what’s the difference between what we see and what we believe that we see?

AK: So, this concept of seeing is believing: do these concepts coexist? Seeing and believing, are they compatible or do they even go together at all?

OE: If being a painter has taught me one thing it is that vision is not very reliable. We think that we just need to open our eyes and let light in as if they were a camera. But it’s not how it works. Vision is also an outward action. Your brain is busy projecting a model of the world, and constantly comparing it to an influx of data. You mostly notice the things that are different from your expectations or that stand out from a pattern. This is a more cost-effective way given our limited resources. Also, you constantly complete missing information or assume it is there. And on top of that, in order to see, light needs to be quickly transformed in the darkness of our brain into chemical reactions and pulses of electricity se we can just “see.” So, vision is never passive, it is always active. And it is influenced by what you expect to see and by what you believe is out there.

AK: Like we see what we want to see, yeah?

OE: Exactly, you see what you want to see, and what you want to see is mostly things that benefit you as an organism. It is ingrained in our evolution. If you want to hunt a rabbit running in the grass, you will likely see it when it stands out from the pattern of the grass, either by its color or by its movement. Coming back to painting, paintings also carry a pattern with them, an expectation. You walk into a museum and your mind anticipates the paintings you are about to see. You expect a landscape, an interior scene, a portrait, a still life, and so on.

Oren Eliav Studio. Photo: Shira Linde

AK: Yes, like History painting…

OE: Yes, also History painting. So, in my work, I consider the viewer’s expectation, their supposed inner models of a painting. It’s about this transition between “Oh, I see a landscape painting’” to “Wait a second, something is wrong, or something is off, or something is not as I am used to.” It’s a subtle thing that I hope happens in the 10 to 30 second range. But anyway, it’s in the hands (and eyes!) of the viewer, who could just as well pass right by without noticing.

AK: I love hearing everything! It’s so true—on one hand, paintings and art in general are a window into our world so it is a window into that outside. But one the other hand it’s our own interpretation of the world. So, what you said, our brain has ways of interpreting something, so it has this duality or system. It’s like the history of art in general, where art is life but also art is not life.