The Vanishing Half: People as Place, Place as People

Education & Community Engagement

The Phillips is hosting a book club about The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett on February 18. Kayleigh Bryant-Greenwell, a Washington, DC-based museum equity strategist, who will be leading the discussion, shares some insights about the book.

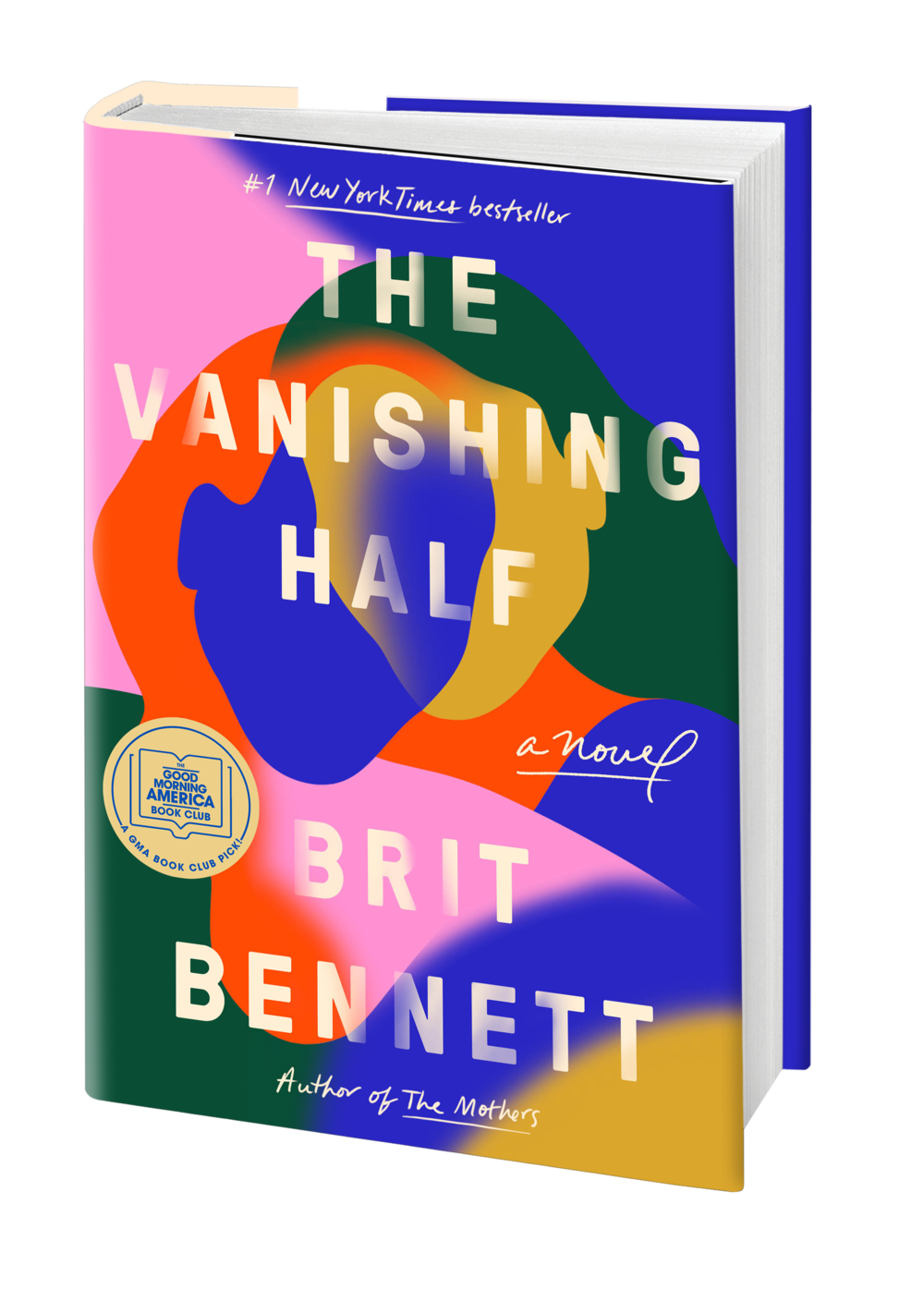

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

There are only two places I’ve ever traveled that left me with an overwhelming down-to-the-bone sense of Place with a capital “P”: London and Vancouver, BC. I visited these iconic destinations on vacation with my husband over the course of our relationship, first visiting London when we were dating. London had such an effect on me as a place—a place that felt entirely enveloping in its character and cadence—that I, we, took the city as the middle name for our first born child. I say all this while reviewing Brit Bennett’s critically-acclaimed masterpiece The Vanishing Half because as a person who has experienced the totalizing power of place, I came to this story, described by critics as traversing time, place, and identity, with certain expectations. And I’m glad to say that not a one of them was met. With such emphasis on place, I expected to be met with a bevy of John Steinbeck and Cormack McCarthy rambling prose describing the look and feel of place in creative but painstaking detail. I am still trying to reconcile why I would ever think that the prose of lauded White male authors would enter into the creative space of a brilliant Black woman writer, but that also holds poignancy to the ethos of the book: racial politics and the biases we hold. To my great surprise and delight Bennett offers a different mechanism of experiencing place. The places traversed throughout the story are done so through the lens of racial experience, its disparities and its inequities. The mysterious town of Mallard is only expressed through the attitudes and exploits of colorism. Los Angeles of the late ‘60s through the early ‘80s is a dilapidated apartment in Koreatown, a beloved gay bar with a raucous weekend drag show, a mildewed performing arts theater, a suburban cul-de-sac reluctant to desegregate. New Orleans is the loneliest city in the world after your twin abandons you and your slum-dwelling existence. This profound singularity of creating place has me rethinking my experiences of London and Vancouver. All good books challenge our thinking and what we’ve always held as truth. Could it be that the joy I experienced in these places had little to do with the places themselves and more to do with how I observed racial politics therein? As a Black woman travelling with an ambiguously brown (and actually half-Taiwanese) man, probably yes. This book meets the cultural moment at a critical time. In the past few years antiracist reading lists have multiplied in demand. For someone looking for more fiction to consider (often these reading lists are populated with nonfiction) I would recommend this. It feels too cliche to say a book has changed my life. But I’ve been holding this reading that outlines the explicitly and inseparable union of place and identity as closely as I do Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisee Cullors’ memoir When They Call You a Terrorist, which does much of the same (and more of course). I first picked up this book in October, having been lent it by a friend who really enjoyed it. I read the first few pages, not even the whole first chapter, and immediately put it down, not returning to it until late January when the Phillips asked if I would host the book club. I thought I would give it another try. In October I was metaphorically knocked out by the immediate opening into colorism, specifically the politicking of a little Black girl’s beauty—and by association her entire worth. It made me dizzy. I am a mother of two daughters. One is White passing, one is a carbon copy of myself down to the caramel skin and dark wavy hair. I bring my own personal details into this review because 1) I had a profoundly personal experience of this book that I think may be shared among many readers and 2) I can personally attest that colorism is still as relevant an issue today across the country as it was in 1968 Deep South. Families are still harmed by social expectations of race and racial familiarity. For this reason I hope that readers do not consider this masterful American story a perfect time capsule, but an illustration, and a caution, in the spirit of this very moment. Kayleigh Bryant-Greenwell (@KayleighBinDC) is a Washington, DC-based museum equity strategist. As Head of Public Programs with the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Renwick Gallery she is responsible for an extensive calendar of programs across two museums, leading new outreach and inclusion initiatives towards developing new audiences and cultivating public engagement. In 2020 she worked with the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum to develop a new initiative on race and community. Additionally she participates in the Museum As Site for Social Action and Empathetic Museum movements. She serves on the Board of Washington Project for the Arts and previously served as the DC Chapter Co-Chair of ArtTable.