Part 2: Behind the Scenes with Jacob Lawrence and the Migration Series

Collection

Phillips Head Librarian Karen Schneider shares the story behind Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series.

Read part 1 of this blog post.

Learn more on the Phillips’s Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series website.

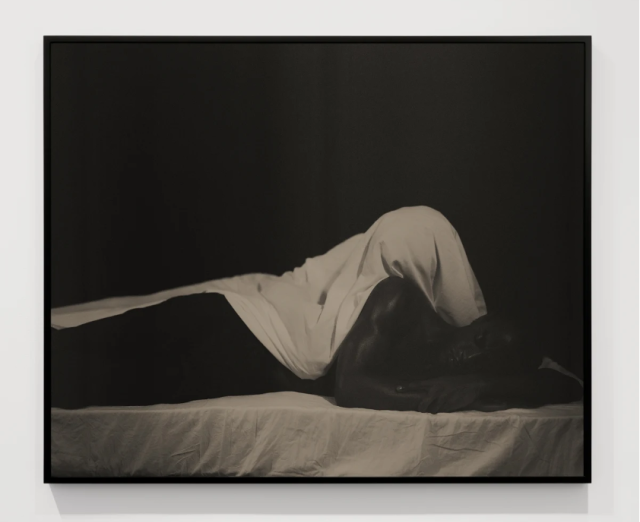

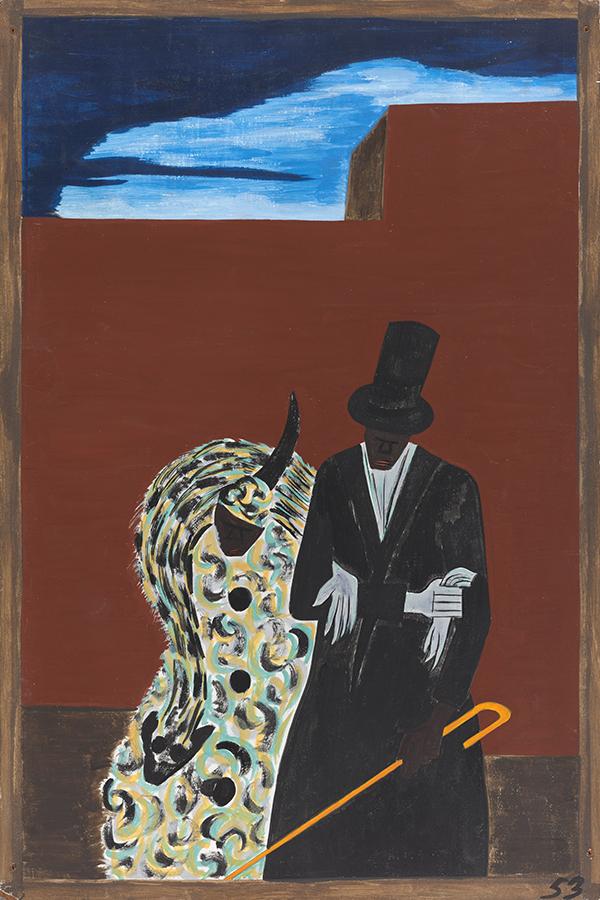

Lawrence’s approach to painting was unique. A close look reveals a small hole in each of the four corners of the panels. Lawrence filled the back of a piece of blank paper with pencil marks, and tacked the paper to the four corners of each panel. Through a process akin to using carbon paper, the image was transferred to the surface of each painting by following the outlines of the drawing with a pencil. As Chief Conservator Elizabeth Steele has written, Lawrence’s work was a balance between precision and spontaneity, representation and abstraction. The pencil drawing gave him an overall structure for each work, but he felt free to improvise. Conservation studies of Panel 53 reveal that Lawrence improvised the free flowing design on the women’s dress and feather boa.

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel no. 53: African American, long-time residents of northern cities met the migrants with aloofness and disdain., 1940-41, Casein tempera on hardboard, 18 x 12 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1942

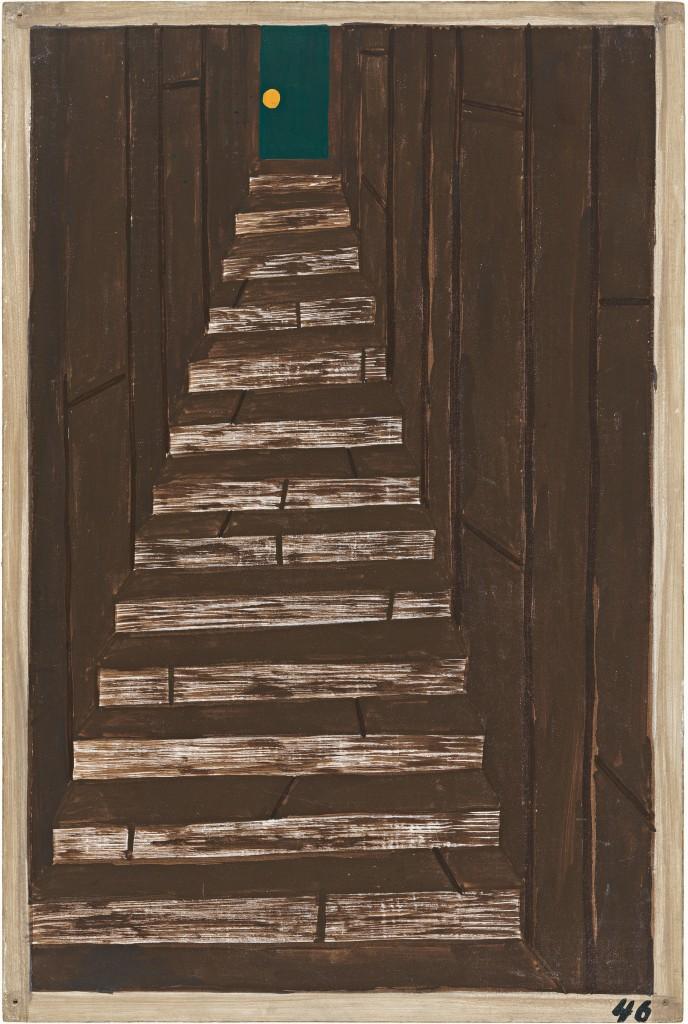

Instead of the typical approach of completing each panel before moving on to the next, Lawrence applied all areas that were black in panels one through 60. He then returned to the first panel, moving through all 60 panels in a progression from darkest to lightest colors. No preparatory or color drawings exist. It is remarkable that Lawrence could keep the color arrangements so clearly in his mind. Tempera paint dries quickly and is not a forgiving medium, so any mistakes would be immediately apparent. Remarkably, the 60 paneled series does not contain any visible mistakes. Visitors may be surprised to learn that The Phillips Collection owns only half of the series. When Lawrence exhibited the series at Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery, Adele Levy, daughter of Julius Rosenwald and trustee of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, fell in love with Panel 46. She acquired the even numbered panels and gave them to The Museum of Modern Art. The two museums have benefited from the arrangement, as the two parts of the series provide a meaningful narrative, from slavery and indentured servitude in the south to a new life in the north. The entire series has been reunited on several occasions.

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel 46: Industries attempted to board their labor in quarters that were oftentimes very unhealthy. Labor camps were numerous., 1940–41, Casein tempera on hardboard, 18 x 12 in. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mrs. David M. Levy

I was fortunate to meet Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight on the occasion of one of Lawrence’s exhibitions at the Phillips in 1993. Knight, a painter whose work is in The Phillips Collection, had the regal bearing of the dancer that she was. They went to Lowell Elementary School in the Cleveland Park neighborhood of Washington, DC. The students had been asked to create works of art that were inspired by The Migration Series, and several of the students received awards for their work. Lawrence could have easily given a general acknowledgement to all of the students at once. Instead, as a slide of each student’s work was projected on a screen, he bent down to tell each child what he found unique in their work―perhaps the way they used pattern or the way they juxtaposed complementary colors to make their composition sing. Afterward, he addressed all of the students, telling them, “There is no such thing as failure in art.” He offered several possible approaches to a work that the students deemed unsuccessful, including returning to the painting after weeks or months, turning the piece in another direction, or moving on to another painting, inspired by the work of art that seemed to be a failure. As an artist I found Lawrence’s words inspiring and I think that the children did too. I often tell adults this story when giving a spotlight tour on The Migration Series. They appear touched by Lawrence’s message and seem to take it to heart.