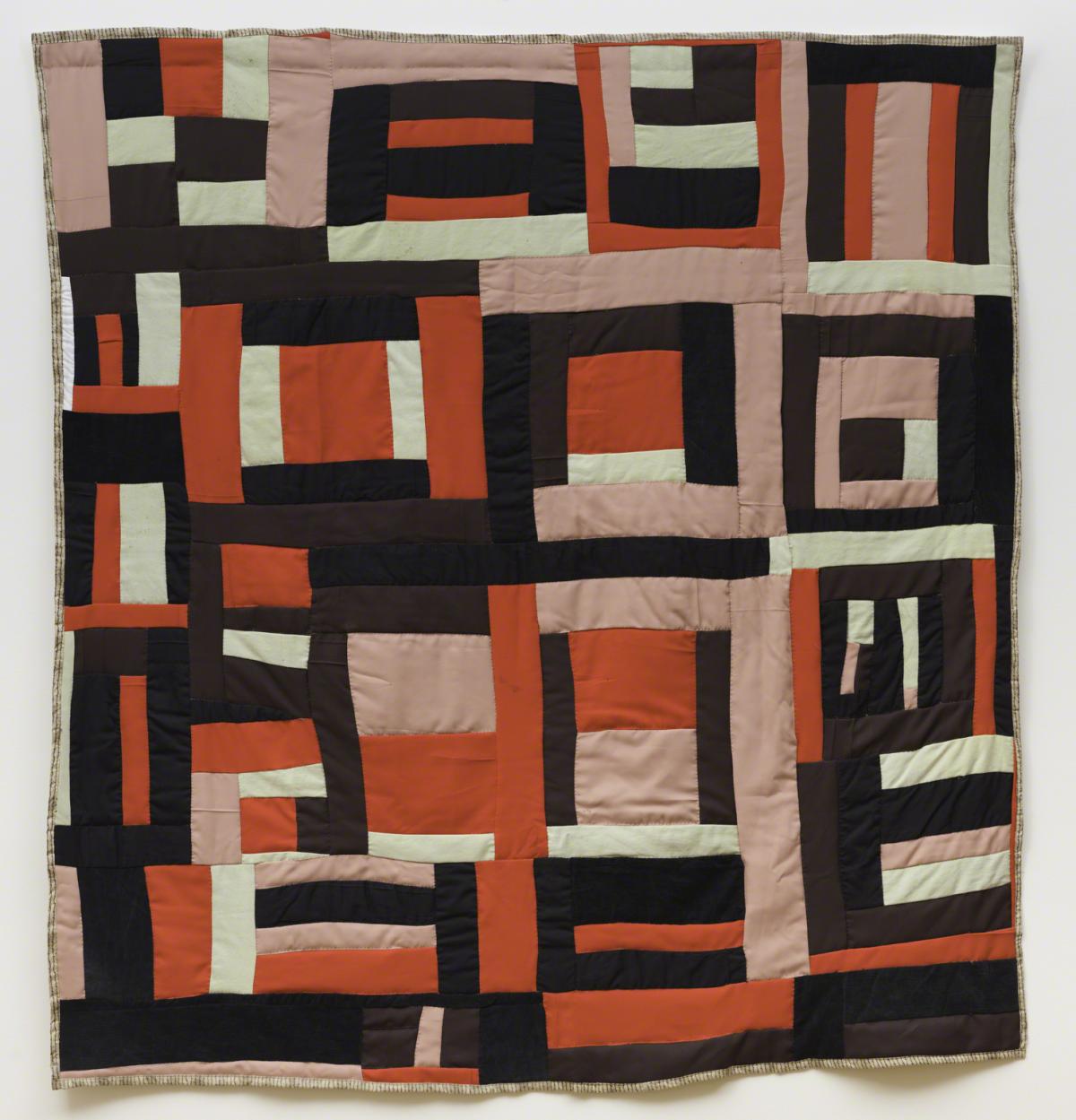

“Housetop” variation

Mary Lee Bendolph ( 1998 )

For me, the power of art lies in its capacity to tell and share stories across time, place, and context. In a recent article,[1] I discussed the restorative impact art can have when it truly resonates with the core of our humanity. The quilts of Gee’s Bend and McArthur Binion’s work DNA: Black Painting: 1 underscore the power of connecting memory, belonging, identity, and personal narrative through art.

The quilts of Gee’s Bend feature memory, personal identity, and narrative. For Gee’s Bend, the tradition of the patchwork quilt was born of scarcity and resourcefulness, arising when shortages of cloth called for the inventive salvaging of fabric scraps and remnants.[2] The transformation of mundane and overlooked objects into extraordinary things is a practice of conversion that Binion too has mastered.

Similarly, Binion intertwines autobiography and personal experience with the fiber of his creations. In works such as DNA: Black Painting: 1, he employs grids, hand-drawn lines, and photocopied versions of his birth certificate. Though his work is deeply personal, incorporating numbers from his phonebook and other private ephemera, Binion’s biographical insertions create access points for others. For example, the materiality of his birth certificate, which designates his race as Black, calls forth the “one-drop rule”[3] and sheds light on the social conditions and perspectives that shaped his life and the lives of millions of others.

In these ways, the Gee’s Bend community’s and McArthur Binion’s works speak to a universal experience of Black people in the United States, stressing the ways racial boundaries were enforced and understood, the ways people survived and even thrived despite that system.

The interplay of medium and narrative in the work of Gee’s Bend and of Binion exemplifies how objects and simple forms can create language.[4] As the chief diversity officer of The Phillips Collection, I fix on language as the entry point for larger conversations that our society needs to have about race, equity, and community. We need artists to catalyze these conversations by creatively infusing humanity into topics that are often nuanced and messy, that require us to look at our history and actions critically, and to take responsibility for things we would much sooner forget.

Stories have been found to trigger chemical responses in our brains that are associated with empathy.[5] Now more than ever, we need that empathy to bridge the divides in our communities and remind us of all that unites us. Binion and the quiltmakers at Gee’s Bend, alongside many others whose work is exhibited at The Phillips Collection, help us to do just that.

1. https://www.aam-us.org/2020/02/05/thetransformative-power-of-inclusive-storytelling-inmuseums/.

2. See https://www.soulsgrowndeep.org/gees-bendquiltmakers.

3. According to the one-drop rule, a social and legal principle of racial classification historically prominent in the United States in the twentieth century, a person with even one ancestor of African heritage (“one drop” of Black blood) is considered Black. Extensive literature on the one-drop rule attests to its persistence today.

4. See https://www.artspace.com/magazine/interviews_features/qa/in-a-predominately-white-artworld-mcarthur-binion-had-to-make-himself-up-tosucceed-54340.

5. See https://hbr.org/2014/10/why-your-brain-lovesgood-storytelling.

Text by Makeba Clay, adapted from Seeing Differently: The Phillips Collects for a New Century (The Phillips Collection in association with Giles, 2021)