Memory Palaces

The art of William Christenberry, Beverly Buchanan, and Clarence John Laughlin, are firmly rooted in the architecture and structures of the American South, as well as the people and communities that inhabit it.

An anonymous monument sitting atop red Alabama earth; a cabin made of sticks with a slim opening in lieu of a door; a plantation house doubled, its surrounding trees blurred into black smudges. These images, conjured by William Christenberry, Beverly Buchanan, and Clarence John Laughlin, are firmly rooted in the architecture and structures of the American South. Drawing from their own experiences of living and working in Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana, respectively, each artist depicts structures taken from both their memories and imaginations. Through their work, which spans painting, drawing, and photography, Christenberry, Buchanan, and Laughlin articulate the architectural variance within the Southern landscape, as well as the people and communities that inhabit it.

A memory palace is a technique in which one visualizes a structure to house different memories. In a 1989 essay, the artist William Christenberry used the phrase to describe his photographic and sculptural practices of integrating his recollections of locations in Hale County and Tuscaloosa, Alabama, into his work. Christenberry was born in Tuscaloosa in 1936. During the summer, he stayed with his grandparents in Hale County, a rural enclave south of Tuscaloosa. Christenberry’s time there deeply impacted him, and he would go on to draw on his childhood memories throughout his career. Christenberry began taking photographs as a child, using a Brownie camera gifted to him by his family. As a young artist, he was inspired by the work of writer James Agee and photographer Walker Evans. Like Christenberry, Evans photographed Alabama, capturing the realities of rural poverty. In the 1960s, Christenberry would meet Evans, who encouraged him to take his photography practice seriously. That same decade, Christenberry moved to Washington, DC, where he would spend the rest of his life. There he met Walter Hopps, director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art and a noted curator, who encouraged him to exhibit his snapshots. [1]

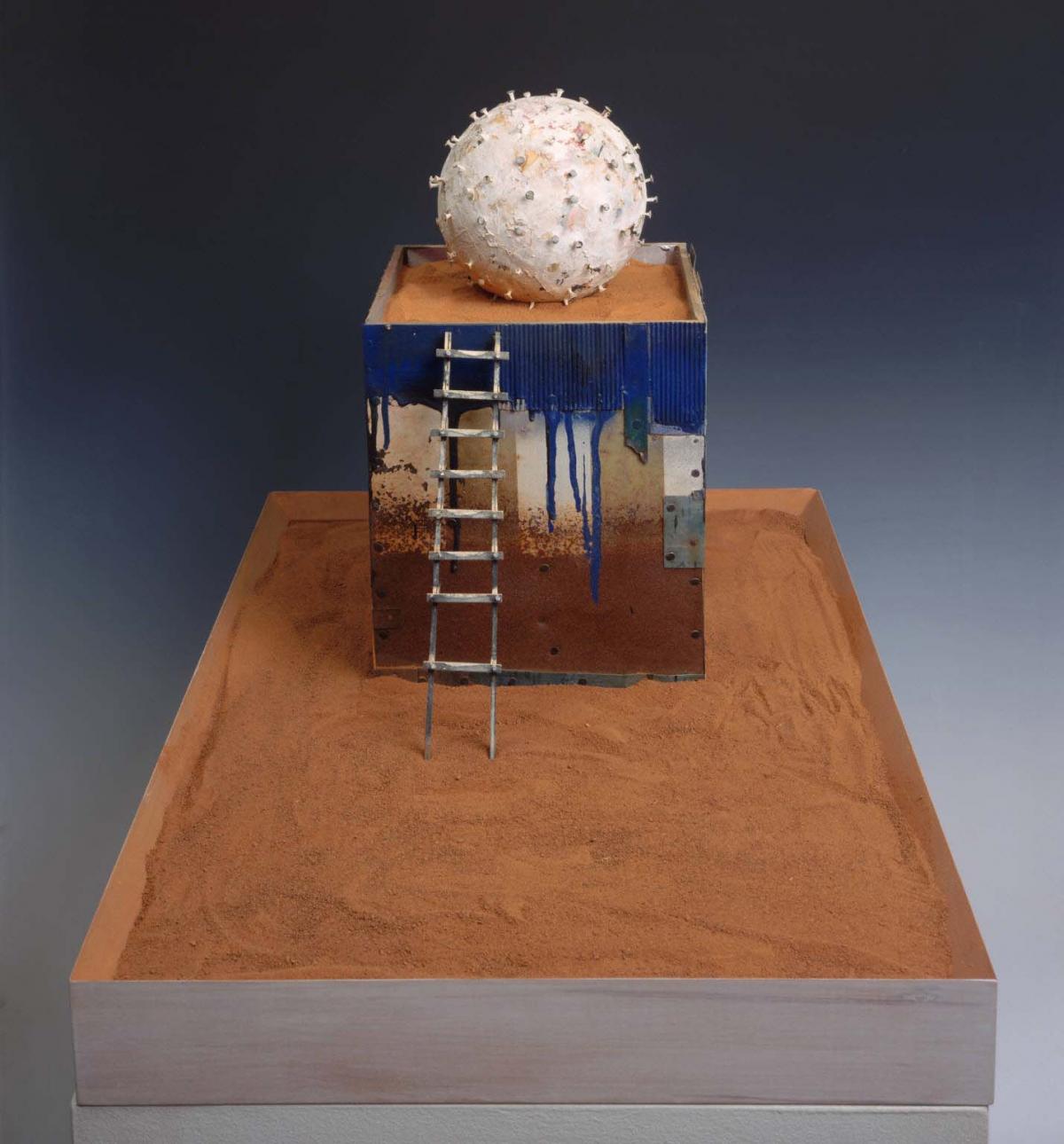

In the early 1980s, Christenberry began creating Southern monuments. These were not the commemorative bronze or marble sculptures generally associated with the South, but abstracted structures meant to evoke the feeling of something monumental. Christenberry’s practice was inextricably linked to his upbringing in Tuscaloosa. Even after establishing himself in DC, Christenberry would make regular pilgrimages to his hometown, and he would return with Alabama soil from Hale County. He used this soil to physically embed the Alabama landscape into his work. In Southern Monument XI, Christenberry places a white sphere studded with nails atop a steel, house-like structure. The sculpture, like the other works in this series, includes a sphere and a ladder resting on a bed of Alabama soil.

William Christenberry, Southern Monument XI, 1983, Wood, sheet metal, metal signs, roofing materials, nails, red soil, and paint, 19 x 28 1/2 x 19 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Philip M. Smith, 2004

In addition to sculpture, Christenberry also engaged with the Southern landscape through photography. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, he began to pair his practices, creating sculptures from photographs he took in the South. Red Building in Forest, Hale, Alabama, shows an abandoned building in the woods. His photograph of a red brick schoolhouse with a doorway sealed by a red brick wall includes aspects of Surrealism. He recreates this image in a replicated sculpture. When viewed together, these works create a textural portrait of the American South, a blend of isolation and the uncanny, infused with a Gothic Surrealism that characterizes much of Christenberry’s work.

Artist Beverly Buchanan was born in Fuquay, North Carolina, and was raised by her great-aunt and great-uncle in Orangeburg, South Carolina. Buchanan’s great-uncle served as dean of the School of Agriculture at South Carolina State College, and she would accompany him to visit farmers and sharecroppers throughout the state. These trips and experiences with vernacular architecture impacted Buchanan greatly. After attending Bennett College in Greensboro, North Carolina, and Columbia University in New York to obtain advanced degrees in public health, Buchanan relocated to Macon, Georgia, in the late 1970s. There she began to truly dig into Southern architecture, inspired by the buildings, shacks, and ruins found throughout the landscape. These structures shared a sense of forgottenness that inspired Buchanan to create her own stories or “legends” around their genesis.[2]

Like Christenberry, Buchanan blurred the lines between reproductions and original creations in works she referred to as “groundings.” In discussing her practice, Buchanan stated: “My work is about, I think, responses. My response to what I’m calling ‘groundings … a process of creating objects that relate to but are not reproductions of structures, houses mainly lived in now or abandoned that served as home or an emotional grounding. What’s important for me is the total look of the piece. Each section must relate to the whole structure.”[3] Buchanan created these groundings in the form of shacks. For Buchanan, these houses in rural Georgia, which were usually built by poor Black folks, served as a type of portraiture. In this way, she viewed the homes as a more than structures; they were entities imbued with the experiences and emotions of the peoples who inhabited them. In her own words:

When I first started shacks my ideas were really about architecture. There are so many different kinds of shacks and I’m basically interested in structure… . At some point I had to realize for me the structure was related to people who built it. I would look at shacks and the ones that attracted me always had something a little different or odd about them. This evolved into my having to deal with [the fact that] I’m making portraits of a family or person which may recall individuals or families I had met, and I would sometimes add traits from others.[4]

Buchanan also traversed media. Her oeuvre includes vivid paintings and drawings of shacks and solemn slab-like replicas of unmarked, or unnamed, structures. In her untitled and undated sculpture, Buchannan creates a log cabin-esque house with a slim opening in lieu of a door. Above the door is a piece of metal, perhaps a sign or a signature. The work is detached from any and all identification, and asks the viewer to consider its origin, which is mythological in its quietude. In another untitled work, Buchanan changes medium, creating a large-scale oil pastel on paper. Unlike the sculpture, the house is firmly rooted in the landscape, with vivid, lush grass surrounding the building The work is divorced from nature while also recognizing its prominence.

Clarence John Laughlin approached Southern architecture through photography. While Christenberry and Buchanan focused on vernacular architecture, Laughlin’s work centered on decaying antebellum buildings. Laughlin began taking photographs in the mid-1930s, at the height of the Farm Security Administration, which funded photography to illustrate the efficacy and importance of New Deal agricultural programs.[5] The Social Realism ushered in by this program was rejected by Laughlin, who instead leaned into a Gothic, Surrealist aesthetic, referring to himself, perhaps surreptitiously, as the first American Surrealist photographer.[6] After being stationed in Washington, DC, from 1942 to 1946, Laughlin returned to New Orleans and began to photograph dilapidated mansions. According to Laughlin, these structures reflected the Southern preoccupation with “past splendors, the fear of the present, the kind of romanticism that implies that only what is dead is beautiful.”[7]

In The Waters of Memory, Laughlin captures a dilapidated plantation house that is shot as if observed through water. His titles, always evocative and deeply poetic, imply that the building is viewed through a lens of memory that blurs its edges. The created image includes a doubling effect common in Laughlin’s work. This technique can be seen as a reference to the blurring of time, the way the past bleeds into the present. His capturing of the decaying mansion also touches on the notion of nostalgia and how we can tether ourselves to the past in ways that enrich our lives as well as in ways that fray our ability to move forward.

Clarence John Laughlin, The Waters of Memory, 1947, Gelatin silver print Acquired from the artist, 1948

In his 1945 photograph The Besieging Wilderness, Laughlin takes a more straightforward approach. As in The Waters of Memory, Laughlin’s subject is a plantation house, but instead of employing experimental techniques to distort the image, he taps into his documentarian roots. The house is in disrepair; its façade is tarnished by time. The title of the work draws attention to the encroaching vegetation that is beginning to overtake the once opulent building. This work also serves as a reflection on the passing of time, revealing the material impacts of abandonment and signaling the brutal systems that propagated this style of architecture, most prominently slavery. The use of the word besiege in the title underscores that this shift in structural status was not relinquished lightly but by force.

Clarence John Laughlin, The Besieging Wilderness, 1945, Gelatin silver print, 10 5/8 x 13 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired from the artist, 1945

Despite their varied practices, each of these artists engages with the South, privileging their personal connections with the landscape. For Christenberry, his work provided a visual record of the places he first encountered as a child. In his own words: “I see a kind of poetry or poignancy of these things that are disappearing. The South is changing rapidly… . These things that I’ve photographed, that I’ve made sculptures of, that I’ve drawn and painted, are not gonna be around much longer.”[8] His practice of photographing the same places and structures over the course of many years reflected both the impact of time and the role memory plays in the visual preservation of these locations. For Buchanan, structures were an entry point to people. In the 1990s, she created a series of one-page descriptions of buildings and the people who inhabited them.[9] These writings, given titles such as “Richard’s Home 1993” and “Three Burned Shacks (The Ella Jenkins House, the Lula Smith House, and the Roderick James House),” provided brief and intimate portraits of the people and dwellings she encountered. Laughlin was less interested in personal narratives and more focused on the poetic, psychological, and emotional resonances of the dilapidated structures of the South, most often in Louisiana. Together, these artists provide a view of the South that spans geography and is reflective of both their personal interests and larger artistic philosophies. When viewed together, these works speak to the diversity of the American landscape and provide variegated revelations of what it means to be shaped by and emerge from Southern architecture.

[1] William R. Ferris, “Those Little Color Snapshots: William Christenberry,” Southern Cultures 17 (2011): 61–70.

[2] Beverly Buchanan biography, Andrew Edlin Gallery, https://www.edlingallery.com/artists/beverly-buchanan.

[3] Beverly Buchanan, July 24, 2016, Arena for Contemporary African, African American and Caribbean Art, https://africanah.org/beverly-buchanan-1940-2015/.

[4] Artist Statements and Writings by Beverly Buchanan, 1981–2001, Box 2, Folder 24, page 46, Beverly Buchanan papers, 1912–2017, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://transcription.si.edu/view/41785/AAA-AAA_buchbeve_3248312.

[5] Michael L. Carlebach, “Documentary and Propaganda: The Photographs of the Farm Security Administration,” The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 8 (1988): 6–25.

[6] A. J. Meek, Clarence John Laughlin: Prophet without Honor (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007), 35.

[7] Meek, Prophet without Honor, 27.

[8] William Christenberry, “William Christenberry: Time & Texture,” High Museum of Art, January 28, 2019, YouTube Video, 5:17, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Ejc_OYACDM.

[9] See Artist Statements and Writings by Beverly Buchanan, 1981–2001, https://transcription.si.edu/project/41785.