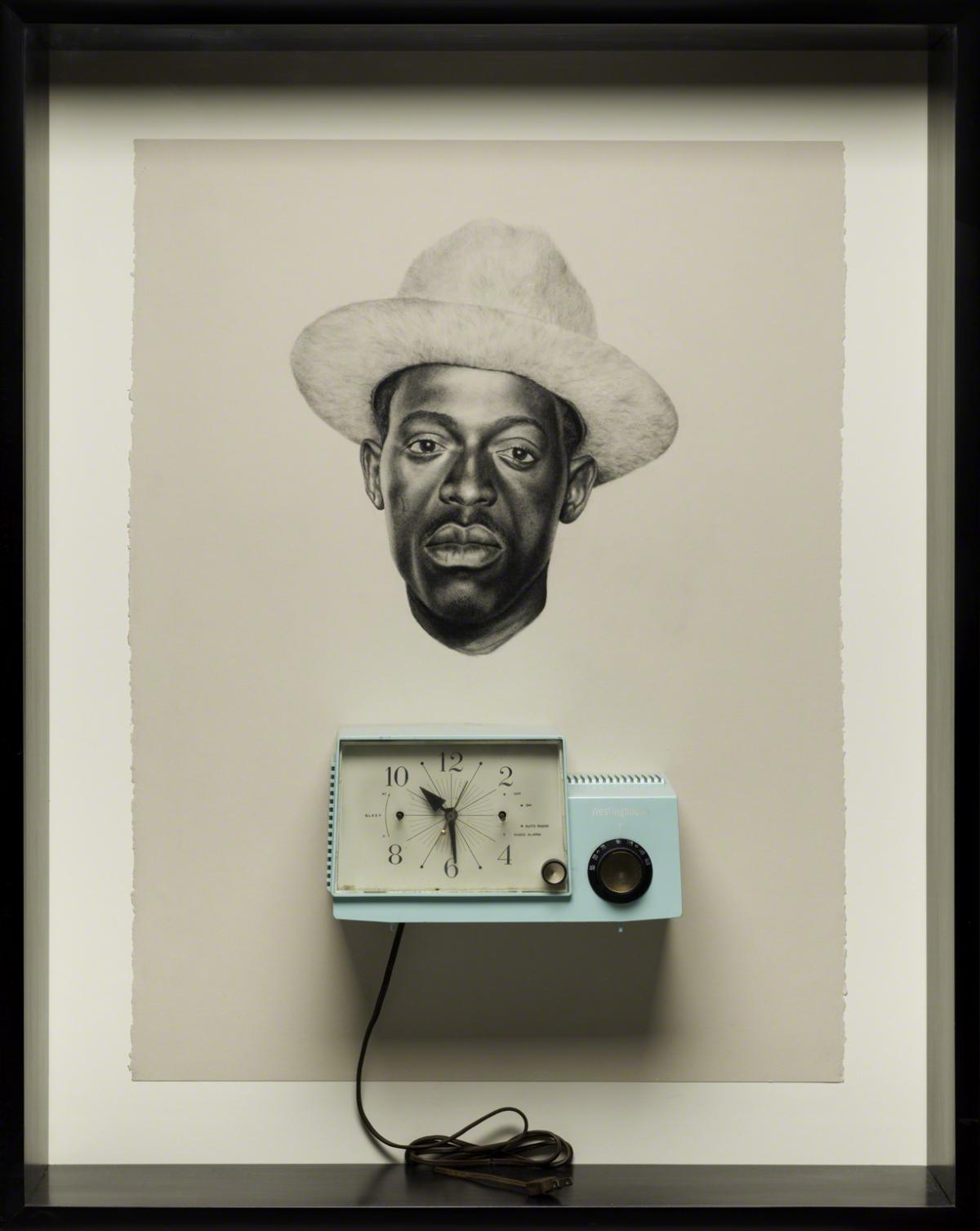

Kin XXXV (Glory in the Flower)

Whitfield Lovell ( 2011 )

With an exquisite, delicate hand, a pluralistic narrative in the diasporic galaxy is created with metaphoric planes and sfumato contours of the Southern human experience: the times of a segregated South, a map bifurcated by barbaric domestic policies and a frantic frequency of civil resolution. Whitfield Lovell’s multimedia cocoons of graceful fluidity capture and freeze the in-between and bottom-of-the-stairwell happenings: the characters in the jook joint located at the crossroads, sipping on fiery brown liquids, as soulful 45-records spin in the Seeburg; the characters in the secret parlor upstairs, who bet their weekly earnings on the suit of spades. These venues are not listed in the Green Book and the faces inside are not in the history books of greatness next to Bayard Rustin or Fred Shuttlesworth. Lovell forages and obtains the IDs of these faces of David Ruffin’s “Common Man”—everyday people, whom Lovell reframes, reforms, rejoices, repurposes, juxtaposes, and masters, making of these subjects masterpieces in dialogue with particular objects.

Kin XXXV (Glory in the Flower) is a cosmology of Arabic numerals, a Sumerian sexagesimal system of time, symbolic and cosmic panache. The golden ratio is purposely skewed in an asymmetrical wonder. 10:29 is the catatonic time on the coral blue Westinghouse Tube Model H-78415. The color is soft, feminine, calming, and playful. The time captures a plethora of possibilities of a post-traumatic, high-cortisol fervor. There is a centripetal gestural dance with the hands of the clock and the numbers: never flush, they flirt. Over the location of the heart, the orbital dial appears like a stethoscope’s chest piece and bell. The T marker is to the right of the 9 and over the zero, indicating a 90.1 MHz frequency, perhaps. A horizon of furled dust lies on the floor of the radio: skin cells, fibers and particles from midcentury. With gravitational sensitivity, the electric cord falls past the bottom margin to the floor of the frame, coiled and extended like a cobra, balancing the intricate nuances of the lower half of the composition.

The handling of the chiaroscuro with the Conté is so masterfully invented, from the highlight on the nose to the cast shadow on the right, under the brim of the hat. The value shifts create superb plasticity, giving depth to the perspective. The values of the portrait parallel the local color and values of the clock, including its cast shadow. Thus, the portrait’s forms, deceivingly, have as many planes as the actual three-dimensional clock, resulting in visual harmony of object and drawing. Textures of the hat, hair, and skin make for a painterly surface, more so than a photographic trompe l’oeil simulation. The delicate balancing act of the portrait echoes the gestural dance of the hands of the clock. The head gently leans to its left, the ear hovering over the speaker, Johnny Ace’s “So Lonely” playing on 90.1. Tears border the lower eyelids, reflecting the light, reflecting bravado, reflecting deep pain. The lips remain poised, mirroring the lips of an Ife sculpture, in all its coolness.

Text by Ellington Robinson, adapted from Seeing Differently: The Phillips Collects for a New Century (The Phillips Collection in association with Giles, 2021)