Curating Collections

How are exhibitions formed?

Museum curators manage and oversee museum collections. They make decisions about what to display and how to display it.

- How would you curate an exhibition?

- What story would your exhibition tell?

- How would you juxtapose artworks?

Installation View from Seeing Differently: The Phillips Collects for a New Century, 2021, Photo: Lee Stalsworth

Create your own exhibition!

As you curate your exhibition, consider:

- How might you arrange the artworks?

- Is there a theme or idea you want to explore?

- What stories can you tell about the artworks by placing certain ones next to each other?

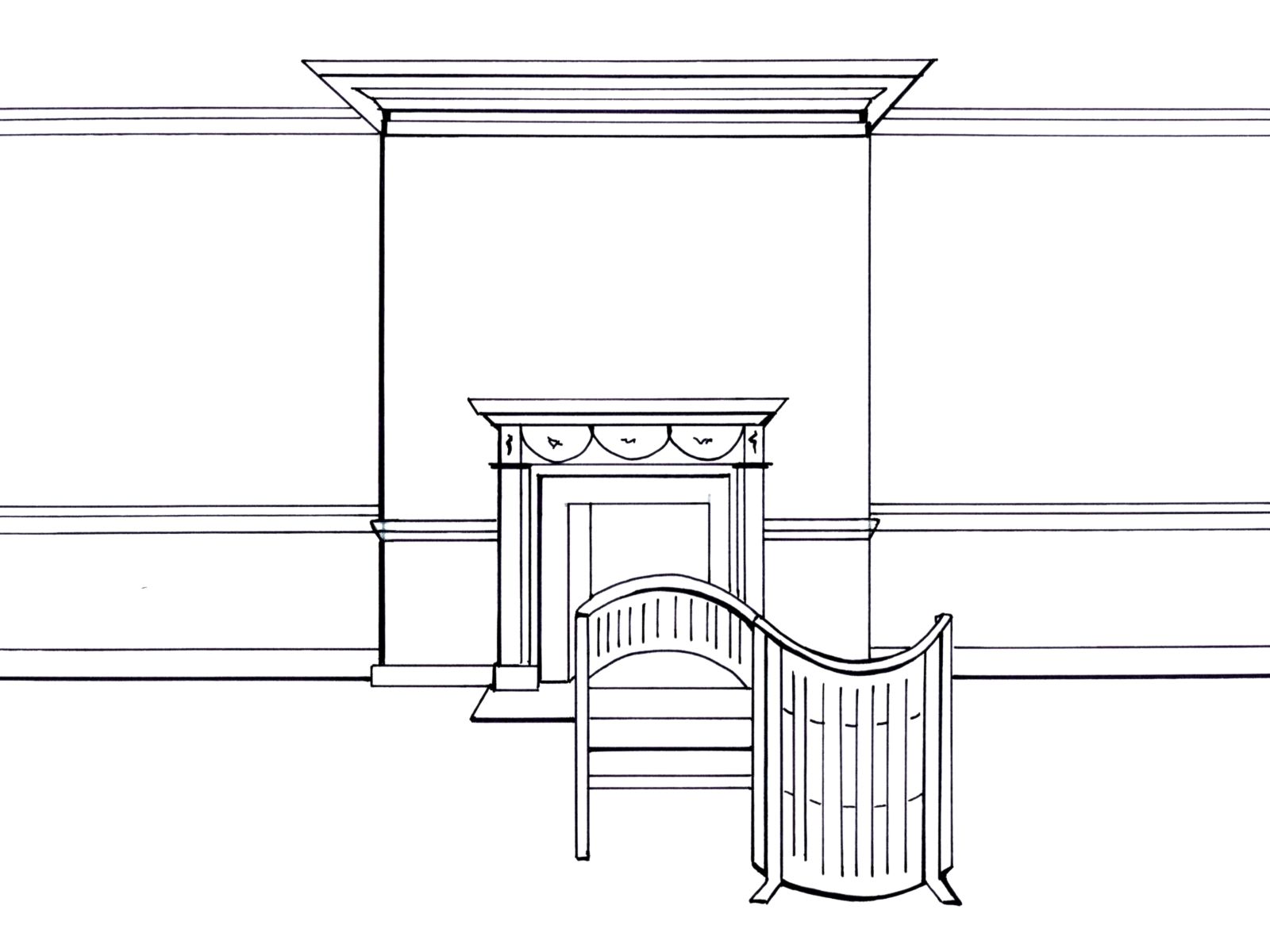

Racquel Keller, Line Drawing of Phillips Collection Gallery, 2021

Spend time looking closely at the artworks below.

Click to enlarge the image and learn more about the artwork. On the next page, use some or all of these artworks to create your own virtual gallery.

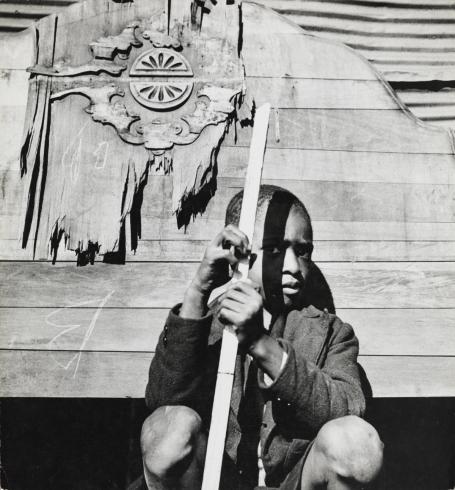

Esther Bubley

A Child Whose Home Is an Alley Dwelling near the Capitol

1943

Gelatin silver print

10 7/8 x 10 1/8 in.

Gift of Cam and Wanda Garner, 2012

Esther Bubley photographed A Child Whose Home Is an Alley Dwelling near the Capitol for her “Around Washington” series. This image depicts a young boy from one of the overcrowded settlements constructed in the DC alleys for poor and working-class families. These alley dwellings survived into the 1940s.

Bubley was one of the first women in the U.S. to support herself as a freelance magazine photographer. Influenced by the documentary images taken for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), Bubley left the Midwest at nineteen in search of a career in the nation’s capital. Using a handheld Rolleiflex camera and a quick point-and-shoot style, Bubley photographed the rhythms of city life. She unobtrusively framed the private moments of sensitive subjects.

The Phillips holds the second largest collection of Bubley’s photographs in the Washington area after the Library of Congress. These images showcase Bubley’s extraordinary storytelling and her eye for the poignant details of everyday life.

Text by Renée Maurer, adapted from Seeing Differently: The Phillips Collects for a New Century (The Phillips Collection in association with Giles, 2021)

Esther Bubley, A Child Whose Home Is an Alley Dwelling near the Capitol, 1943

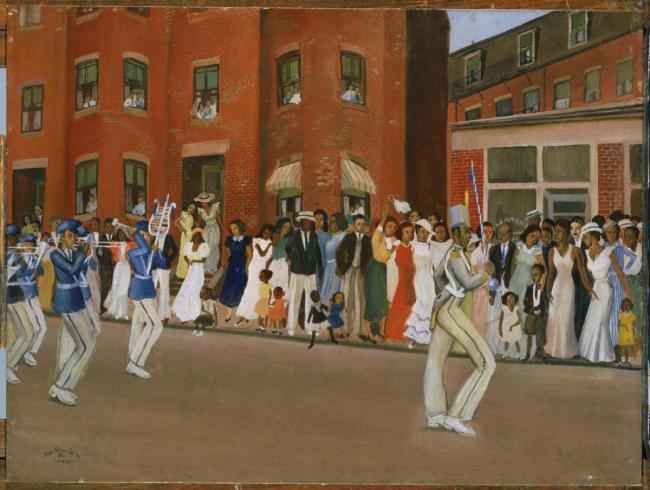

Allan Rohan Crite

Parade on Hammond Street

1935

Oil on canvas board

18 x 24 in.

Acquired 1942

For Parade on Hammond Street, Allan Rohan Crite was inspired by a parade he saw near his home in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood. Using predominantly warm, vibrant colors, he paints his neighborhood’s residents dressed in their best clothes, gathered to watch a parade before Sunday church services. They gather in front of brick buildings, which were typical of the neighborhood at the time.

Crite once said, “I’m a storyteller, telling a story of people.” He added, “I started out with my own people in the immediate sense, like the neighborhood, and people in a general sense when I make a neighborhood out of the whole world.”

What stories does your neighborhood tell?

Allan Rohan Crite, Parade on Hammond Street, 1935

Amy Cutler

Idle Spinners

2011

Hydrocal, silk, steel

8 x 24 x 24 in.

Gift of Zöe and Joel Dictrow

Almost all the characters we see in Amy Culter’s artworks are women. In this small sculpture, notice each woman’s face and how her hands are positioned. Cutler invites us to observe this group of women working. They are absorbed in their work. The six women hold a length of hair that creates a circle connecting woman to woman, but keeps us from entering. In some fairy tales, like Rapunzel, hair is charged with magical properties. Here, we do not know what they are working on or what they are trying to achieve. Are these women harnessed to their role and duty? Have they chosen it or has it been chosen for them? In works like this one, we are prompted to recognize the social mores and rules that confine and contain women’s lives.

Amy Cutler, Idle Spinners, 2011

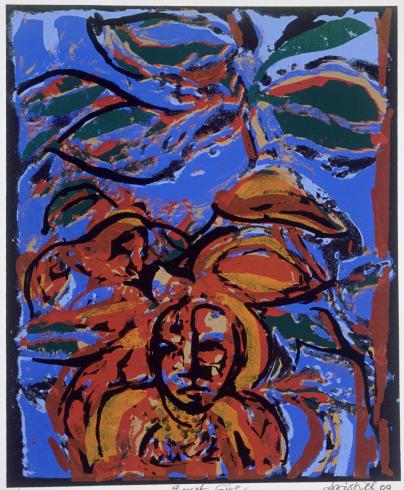

David Driskell

Forest Girl (from the Doorway Portfolio)

2009

Screenprint

15 x 12 in.

Purchase, The Hereward Lester Cooke Memorial Fund, 2009; © Cardinal Point Press

David Driskell was both an artist and a historian who worked throughout his career to push people to acknowledge and recognize the significant contributions of Black artists to American art. As an artist, his work depicted themes such as Black identity, personal and cultural histories, family, religion, and nature. He also collected and showcased the work of Black artists. In reflecting on his legacy, he states:

“If I had a legacy at all, I would hope that it would be one which would relate to the idea that inclusion and diversity in the arts is one of the healthiest things that could be happening in our culture.”

The David C. Driskell Center for the Study of the Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora describes Forest Girl:

“Forest Girl, from the Doorway Portfolio by David C. Driskell, is a riot of blue, red, and black. The torso and head of a figure with long flowing hair rises from the bottom of the piece amid branches and large leaves of the surrounding foliage. In keeping with Driskell’s love of nature, the figure’s placement allows the leaves and branches to occupy the most space, speaking to both the prominence of nature and the position of people within the natural world.”

David Driskell, Forest Girl (from the Doorway Portfolio), 2009

John Edmonds

Untitled (Hood 2)

2016

Archival pigment print

20 x 14 in.

Promised Gift of Vittorio Gallo, 2018

John Edmonds approaches strangers on the street asking to take their portraits. He explains his Hoods photographic series:

“It was a project about a simple item of clothing worn by many people of all races, ages, and genders. I was interested in how people would respond to this racially coded item in images where the identity of the wearer was completely obscured or opaque…

“I’m working in a public space in this very sore-thumb kind of way, with a camera on a tripod, when I’m making those pictures. I have all these hooded jackets with me, and I’m casting people as they walk by, costuming them with clothes from my own wardrobe. I often talk about those pictures in terms of “self-portraiture”—in quotation marks, because I’m not necessarily the subject. The self-portrait can be located in the viewer locating him- or herself within the dynamic of looking. It’s a figure in a hood, but the issue is how as a society we racialize and create fictions around those we do not know…

“What is important is for a picture to make you slow down and ask yourself: what am I seeing?”

John Edmonds, Untitled (Hood 2), 2016

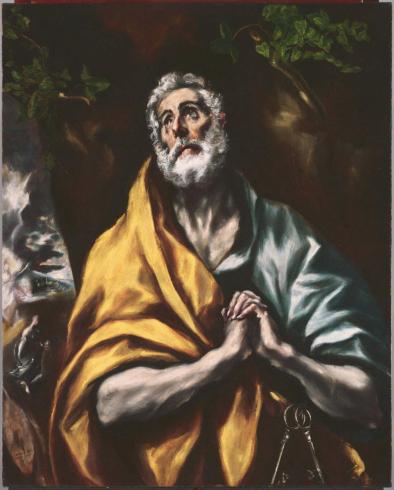

El Greco

The Repentant St. Peter

1600-05 or later

Oil on canvas

36 7/8 x 29 5/8 in.

Acquired 1922

El Greco’s Christian faith was central to his work. He painted the subject of the Repentant Saint Peter six times. A tormented Saint Peter looks up to God with tears in his eyes, pleading for forgiveness. His eyes express the depth of his regret over the betrayal of Jesus three times. The keys to Heaven, given to him by Christ, hang on his wrist.

El Greco paints Saint Peter as profoundly human. Notice the realistic depiction of the musculature of his arms, his curly gray hair and beard, his thick neck. El Greco’s ability to articulate private feelings and deep emotions struck a chord with artists in the centuries that followed.

Duncan Phillips acquired this painting in 1922. While it is outside his typical collecting taste for 19th and 20th century artworks, he recognized the importance of El Greco’s stylistic innovations for modern artists.

El Greco, The Repentant St. Peter, 1600-05 or later

Jackie Ferrara

A177 XF 1 3/4 - XS 5/8 - V, A 1 1/4 - V, A 1

1977

Pine

22 ½ x 38 x 26 ¼ in.

Gift of Christopher W. London in memory of his father, Robert D. London, MD, 1991; © Jackie Ferrara

Jackie Ferrara’s wood-stacked sculptures are known to resemble pyramids or ziggurats (a rectangular stepped tower from ancient Mesopotamia). What other architectural formations does this sculpture remind you of? Where do you imagine you might find a design like this?

Notice the repeating patterns, geometry, and negative space in the sculpture. How might the light shine through the slats and holes in the sculpture?

Although this sculpture might come up to only your waist, Ferrara also makes large-scale installations in similar formations. Imagine you were standing in front of this sculpture, except it was 20 feet high! How might it feel standing at the bottom of the sculpture? If you walked up to the top?

Jackie Ferrara, A177 XF 1 3/4 - XS 5/8 - V, A 1 1/4 - V, A 1, 1977

Flor Garduño

On the Way to the Cemetery, [Tixan] Ecuador

1988

Gelatin silver print

16 in x 20 in.

Gift from the Collection of Michael and Joyce Axelrod, Mill Valley, California, 2013

Flor Garduño evokes the present and the eternal by portraying indigenous Mexican people’s daily lives and traditions. Her photographs capture moments of spirituality and death. In Road to the Cemetery, we see a burial procession. Three figures walk down a deserted street, enveloped in a mist of fog. A child’s coffin is tied to the back of the person walking in the middle. The figure on the right carries a shovel. They have their backs to the camera. It’s like we are following them, drawn into their lives.

Flor Garduño, On the Way to the Cemetery, [Tixan] Ecuador, 1988

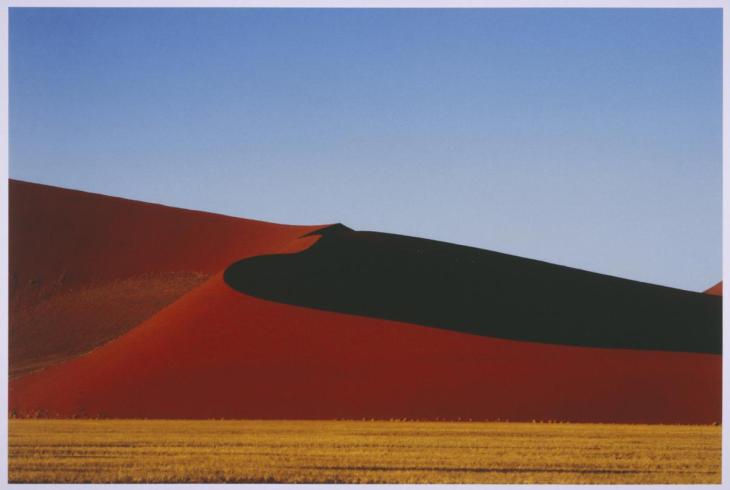

April Gornik

Red Dune (from “America Now + Here: Photography Portfolio 2009”)

2007

Digital c-print

20 x 24 in.

Gift of Carolyn Alper, 2010; © April Gornik

Gornik’s dramatic landscapes are dominated by the sky and devoid of people. Here we see the play of color, light, and form in this panoramic view of the American Southwest. She explains:

“When I first started painting landscapes, I made a lot of paintings from dreams. I never even considered using photographs — I thought that was cheating! And then I was touring around the American Southwest with a camera. Looking at that landscape, I realized that it is more amazing and surreal and astonishing than anything that I could dream or make up, so I decided I’d start to use photographs. I soon realized that the photographs didn’t have enough information for me to copy them exactly, and the more I worked with them, the more I realized that I could trust myself to interfere with my starting points in a positive, creative way.”

Gornik began to alter her photographs to create dramatic scenes like the one we see here. The artist remarked: “Now I make my landscapes so that I can be in them. That’s why I alter them, that’s why I make them somewhat artificial, because I want to take possession of them.

April Gornik, Red Dune (from “America Now + Here: Photography Portfolio 2009”), 2007

Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence

Untitled (New Orleans Series)

1941

Gouache on paper

14 ½ x 12 ¾ in.

Gift of the Phillips Contemporaries, 2001; © 2016 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Gwednolyn Knight Lawrence created this gouache watercolor during her time in New Orleans in 1941. Knight and artist Jacob Lawrence, who had recently wed, went to New Orleans that August in search of an “adventure.”

“We heard about New Orleans and its music, its drama, its romance,” Jacob Lawrence later recalled. It would be their first experience in the segregated South. Although Jim Crow laws meant she “couldn’t go to the museum,” Knight found artistic inspiration in New Orleans’s colorful surroundings, creating charming street scenes.

In this gouache, we see a dynamic interplay of organic and geometric forms. A banana flower has been magnified to fill the center of the composition. The reds and greens stand out against an azure blue sky. The colors of the flower are so bold, we barely notice the woman in an orange dress silhouetted below the flower. The image of the monumentalized flower reminds us of the bold abstractions of Georgia O’Keeffe, an artist with which Knight was familiar. O’Keeffe depicted the same subject of a banana flower in a series of charcoal drawings done on a trip to Bermuda in 1933-34.

Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence, Untitled (New Orleans Series), 1941

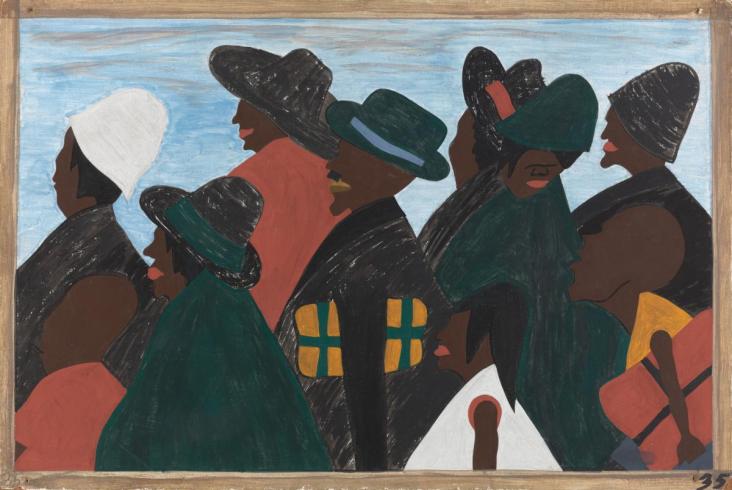

Jacob Lawrence

The Migration Series, Panel no. 35: They left the South in great numbers. They arrived in the North in great numbers.

1940-41

Casein tempera on hardboard

12 x 18 in.

Acquired 1942 © 2016 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jacob Lawrence depicts the broad and complex migration of African-Americans from the South to the North. The 60-panel series captures themes of struggle, hope, triumph, and adversity. Lawrence tells a story that reminds us of our shared history and invites us to reflect on the universal theme of struggle in the world today:

“To me, migration means movement. There was conflict and struggle. But out of the struggle came a kind of power and even beauty. ‘And the migrants kept coming’ is not only a refrain used as the caption for Panel no. 60…, but it is also a refrain of triumph over adversity. If it rings true for you today, then it must still strike a chord in our American experience.”

Lawrence repeats certain words and colors to give the 60-panel series the rhythm of a jazz composition, highlighting the persistence and optimism of those migrating north.

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel no. 35: They left the South in great numbers. They arrived in the North in great numbers. 1940-41

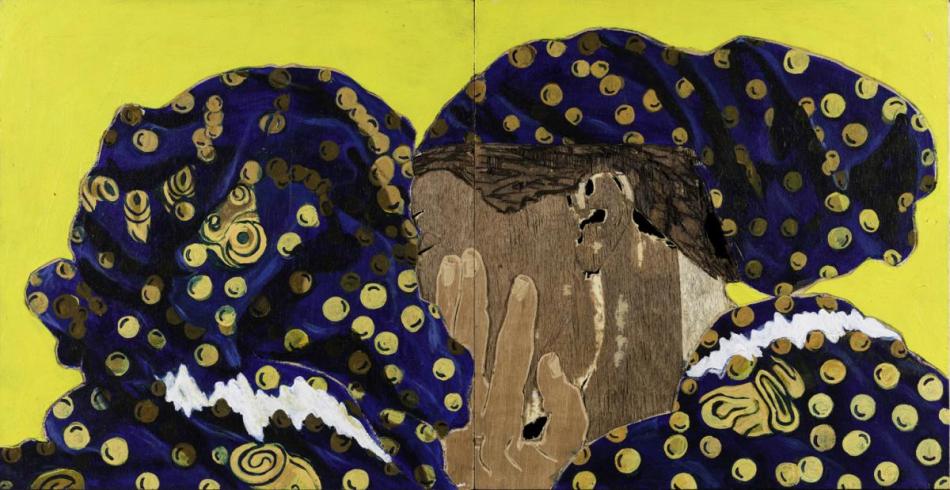

Aimé Mpane

Mapasa, 2012

Acrylic and mixed media on two wooden panels

Each panel 12 ½ x 12 in.

The Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Award, 2012

Congolese sculptor and painter Aimé Mpane works primarily with wood and an adze—a traditional African woodworking tool. He creates sculptures, mosaic-like wall hangings, and portraits carved on wood that explore the character of contemporary Congo, while demonstrating its history. Mpane’s artworks often address the aftermath of Belgian colonialism and the Mobutu regime in Congo, while his brightly painted portraits of the men, women, and children he meets on the streets of Kinshasa give insight into modern Congolese identity. As he has said, “My work tells of hope, courage, empathy, and endurance.”

Mapasa, 2012, was acquired from (e)merge, the contemporary art fair that took place at the Capitol Skyline Hotel annually from 2011-2015. Mapasa is a colorful double-portrait of two sisters, carved out of plywood in Mpane’s signature style. As part of the Phillips’s efforts to grow the international foundation of the collection established by Duncan Phillips, the Phillips has now also acquired a second artwork by Mpane, Maman Calcule.

Aimé Mpane, Mapasa, 2012

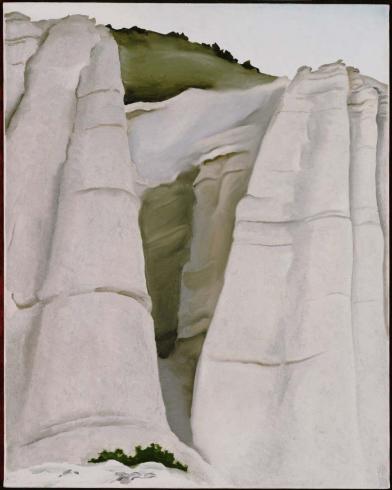

Georgia O’Keeffe

From the White Place

1940

Oil on canvas

30 x 24 in.

Acquired 1941; © 2008 The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

From the White Place refers to the hills near O’Keeffe’s home in New Mexico. In the painting, she highlights the verticality and grandeur of the mountains—strong, sturdy, and unyielding. Her palette is limited to the earthly colors of the landscape—gray and white stone and green foliage and shadows. Though the setting is identifiable, O’Keeffe gives the painting a certain ambiguity as it is devoid of any human presence and it is difficult to distinguish if this is a panorama or a close-up. Instead, she emphasizes nature and the looming hills, which lead our eyes upward toward the sky.

Georgia O’Keeffe sought spirituality within her own life as well as her work. She was drawn to places that evoked a sense of mystical wonder and inspired beauty. O’Keeffe spent a great deal of time in New Mexico, traveling there from New York every summer from 1929 until she made the move permanent twenty years later. The barren landscape, craggy rocks, and untouched earth were a source of great inspiration in O’Keeffe’s work, as she experienced spiritual wonder and serenity in the overwhelming presence of nature.

Georgia O’Keeffe, From the White Place, 1940

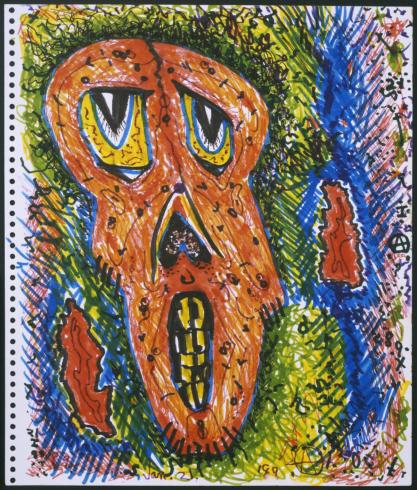

Alfonso Ossorio

Recovery Drawings #4, Book 1

1989

Felt-tip watercolor marker on paper

8 ½ x 10 in.

Gift of the Ossorio Foundation, 2008

Alfonso Ossorio was one of the first members of the Abstract Expressionist movement, which rejected naturalistic images and stressed spontaneous expression. An artist, collector, and patron of both American and European artists, he is one of the most colorful figures of postwar America. Ossorio was born in the Philippines in 1916, and he spent the majority of his childhood in England until moving to the US in the early 1930s.

Throughout his career, Ossorio experimented with conventional and unconventional mediums. His style was informed by his friends Jackson Pollock and Jean Dubuffet, yet differed from them with his interest in surrealism and belief in free and spontaneous gestures. While hospitalized in 1989 and 1990, he created his 42-drawing series using markers and watercolor paper, which became known as the Recovery Drawings.

Alfonso Ossorio, Recovery Drawings #4, Book 1, 1989

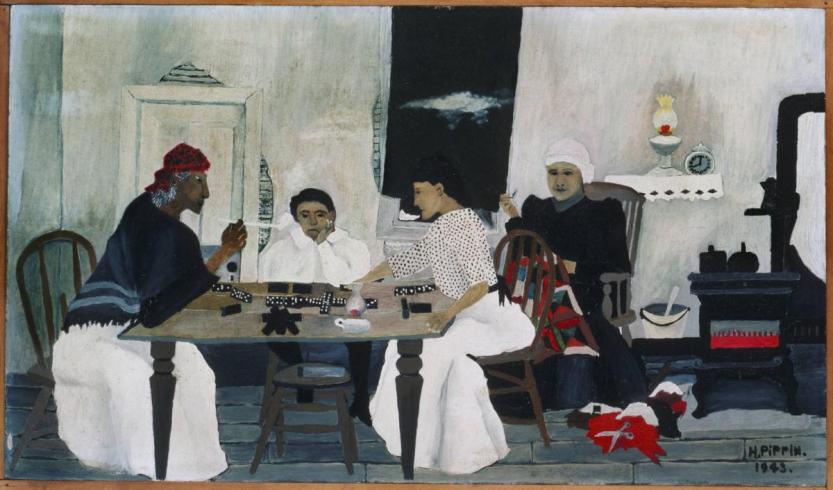

Horace Pippin

Domino Players

1943

Oil on composition board

12 ¾ x 22 in.

Acquired 1943

When he was ten years old, in 1898, Horace Pippin answered a magazine advertisement and received a box of crayons, paint, and two brushes in the mail. From then on, he colored frequently as a child. In 1917, Pippin enlisted to fight in the First World War, but was seriously wounded, crippling his right arm. In 1931, he produced a painting about the war, providing him with a therapeutic outlet for his experiences and becoming the catalyst for his career.

In the 1943 painting Domino Players, Pippin captured the mood of long quiet hours of childhood Sundays. The painting emphasizes the intimate family group enjoying their time together.

Shortly after acquiring the painting, Duncan Phillips wrote: “The (purchase of the) Pippin Domino Players is certainly no mistake and in this case the wisdom of my immediate decision was confirmed on receipt of the picture.”

Horace Pippin, Domino Players, 1943

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Luncheon of the Boating Party

1880-81

Oil on canvas

51 ¼ x 69 1/8 in.

Acquired 1923

This painting by Pierre-Auguste Renoir depicts a group of friends, from various social classes, gathered for a meal and to socialize along the Seine River just outside Paris. Renoir was a part of a group of 19th-century artists called Impressionists. The Impressionists painted scenes of modern life using new techniques, such as en plein air painting (painting outdoors) and painting with small, quick brushstrokes. Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party represents the social, political, and economic changes occurring in late 19th-century France. With the invention of the railroad and socio-economic advancements, many Parisians began enjoying more leisure time.

Shortly after confirming his purchase of the Luncheon of the Boating Party, Duncan Phillips wrote an enthusiastic letter about the acquisition:

“The Phillips Memorial Gallery is to be the possessor of one of the greatest paintings in the world … It will do more good in arousing interest and support for (the Phillips Memorial Gallery) than all the rest of our collection put together. Such a picture creates a sensation wherever it goes.”

In an affirmation of Phillips’s foresight, Luncheon of the Boating Party has become today among the most visited and commented upon paintings in The Phillips Collection.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party, 1880-81

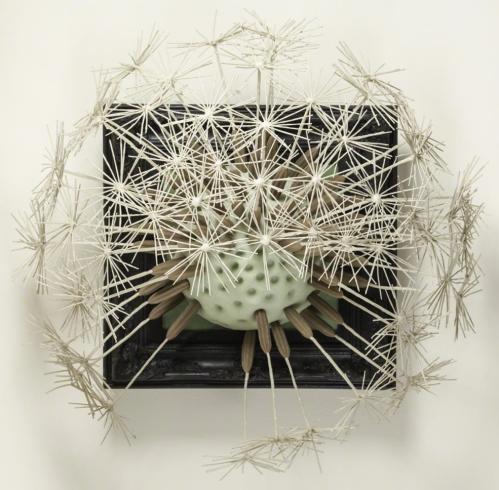

Jeanne Silverthorne

Dandelion Clock

2012

Platinum silicone rubber, phosphorescent pigment, wire

33 x 29 x 16 in.

Purchase, The Hereward Lester Cooke Memorial Fund, 2014

“Dandelion Clock is a contemporary vanitas, a reminder of transience and mortality. It is infected by signs of morbid excess (the giant size), decay (the faded or “blown” flower), and toxicity (it glows in the dark). Collapsing under the weight of history and new technologies, traditional studio practice is an excavation of the past, offering an archeology of loss. Flirting with the genre of the floral painting, Dandelion Clock embraces the baroque exuberance and post-modern melancholy of the nearly extinct.”

-Jeanne Silverthorne

Vanitas are still life paintings that symbolize the brevity of life with images of decaying fruit and flowers, skulls, or household objects such as mirrors, candles, and broken dishes. Themes of decay, ruin, and a perpetual state of collapse underlie Silverthorne’s work. Her work addresses the disappearance of traditional genres such as still life and portraiture in the face of technology- and multimedia-based works.

Silverthorne casts objects from her studio (packing crates, chairs, light fixtures, and electrical cords) or from nature (plants, flowers, and insects) in rubber. With them, she creates modern still lifes that reflect the ephemeral and ever-changing aspects of life and art. By using a modern, synthetic material with “no backbone” (rubber) that adapts to any shape or size, she stresses the mutable character of organic and human-made worlds. Through a displacement from familiar context and a shift in scale (here, by enlarging the dandelion), her work moves from the real to the surreal and gains an absurdist tone.

Jeanne Silverthorne, Dandelion Clock, 2012

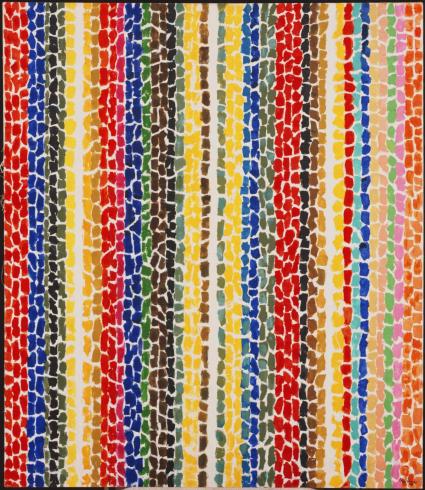

Alma Thomas

Breeze Rustling Through Fall Flowers

1968

Acrylic on canvas

57 ⅞ x 50 in.

Gift of Franz Bader, 1976

“I sat down right in … that red chair in my living room, and I looked at the window. And you can see exactly what I saw, right before my eyes, from where I was sitting in the chair. Why, the tree! The holly tree! I looked at the tree in the window, and that became my inspiration… And every morning since then, the wind has given me new colors through the windowpanes.”

-Alma W. Thomas

When Howard University offered to mount a retrospective of her work in 1966, Alma Thomas wanted to produce something new. She explained, “I decided to try to paint something different from anything I’d ever done. Different from anything I’d ever seen. I thought to myself, ‘That must be accomplished.”’ From the window of her house and her walks around Washington, DC, Thomas enjoyed watching the ever-changing patterns that light created on trees and flower gardens. With the holly tree outside her living room window as her initial inspiration, Thomas created a style that would become her signature: small, rectangular shapes of bright, intense colors merged together in curves, lines, and circles.

Thomas described her subject matter: “I’ve never bothered painting the ugly things in life. People are struggling, having difficulty … No. I wanted something beautiful that you could sit down and look at.”

Reflecting on her use of color, Thomas explained, “Through color, I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man.”

Alma Thomas, Breeze Rustling Through Fall Flowers, 1968

Catherine Yass

Descent: HQ5: 1/4s, 7.2°, 0-2 mm, 20 mph, 180°

2002

Ilfachrome transparency and lightbox

44 ¼ x 55 ½ x 4 7/8 in.

Gift of the Heather and Tony Podesta Collection, Washington, DC, 2010

“I started to deal with… the language and politics of photography. It seems to me that if you want to change things, politically or emotionally, you have to change the terms that they get put in, otherwise you’re going to be always governed by their language and you’re only able to…operate within it. So in order to be able to really speak, I think you have to understand your language. That means, for me, undoing it and starting again or trying to find out how I can best use it. So with photography, undoing it meant doing everything completely wrong, like shooting on the wrong material, maybe tearing it up, maybe overexposing it, maybe putting things through the wrong process, in order to find out what it could do beyond the limitations that have been put on it… I think that’s to find my own voice in some way…

“I’m feeling more explicit about politics as I get older. I’m much more interested in the politics of overturning systems of thought in order to allow the viewer and myself to rethink things, and they can come to their own conclusions. I don’t mind what conclusions they come to necessarily. What’s more important is their thinking. I think it’s a political act to try to make a work which provokes thought and allows people to think for themselves.”

-Catherine Yass

Catherine Yass explores how our environments are constructed and experienced by us. She manipulates the exposure and development of film—for example, by layering a positive and negative transparency—and then displays the images on lightboxes, creating an abstracted view of reality.

What does this photograph remind you of? What’s challenging to you about the photograph? Why?

Catherine Yass, Descent: HQ5: 1/4s, 7.2°, 0-2 mm, 20 mph, 180°, 2002