Honoring the Black Artists of Howard University

Exhibitions & Events

The Phillips Collection Fellow and Howard University student Arianna Adade reflects on the 34th James A. Porter Colloquium on African American Art and Art of the African Diaspora (you can view the livestream of the proceedings at The Phillips Collection on April 5 on YouTube) and the installation of Where We Meet: Selections from the Howard University Gallery of Art and The Phillips Collection (on view through August 15, 2024).

When people think of Howard University, art may not be the initial thought that comes to mind. However, Howard is home to some of the most revolutionary Black artists. From Sylvia Snowden and Lois Mailou Jones to David Driskell and Elizabeth Catlett, Howard is home to trailblazing Black artists that are often under-appreciated in today’s art world.

I had an amazing experience viewing Where We Meet: Selections from the Howard University Gallery of Art and The Phillips Collection. Seeing the legendary Alma Thomas and Elizabeth Catlett’s works side by side was beautiful to witness—Catlett’s black-and-white lithograph adjacent to Thomas’s multicolored acrylic canvas highlighted the remarkable contribution Black women have given to the art world. The unique works of art on view gave me an even deeper appreciation for Howard as a grounding source for Black artistic talent throughout the centuries.

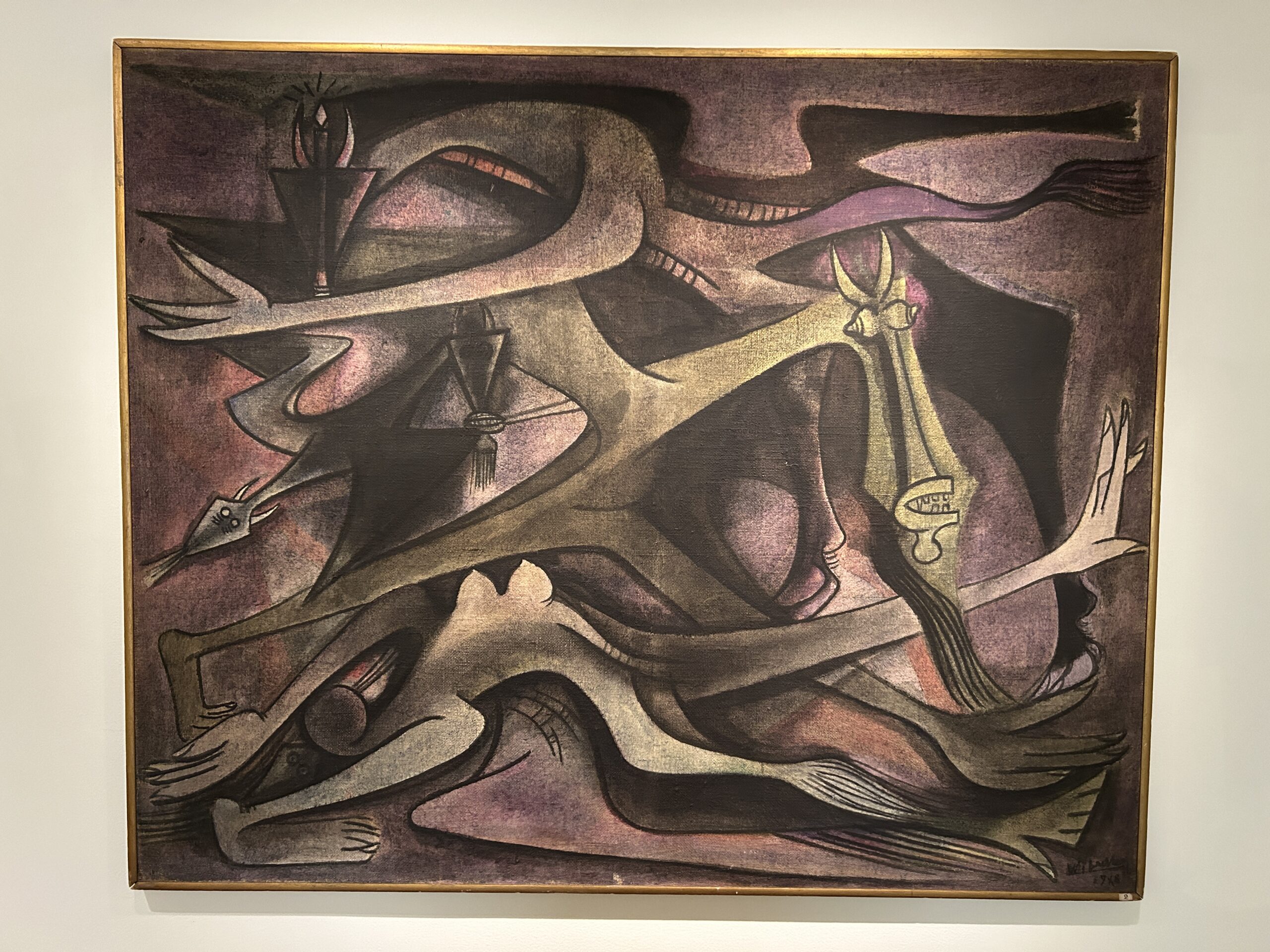

Afro-Cuban art shined brightly within the exhibit, capturing the essence of cultural and ancestral fusions and legacies in Howard’s art collection. Wifredo Lam, known for his contribution to Afro-Cuban artistic expression particularly stood out to me. Howard has always been known as the heart of Black diasporic identities, and it is no different pertaining to art.

The Phillips’s connection to Howard began with the establishment of the Howard University Gallery of Art in 1928 under the leadership of James A. Porter. The Phillips Collection was seen as an intimate space for the art talent at Howard, as many students would come to the museum when they were excluded from other museums during segregation. Howard professor James Lesesne Wells is just one of many artists whom the Phillips family valued and his work was acquired by Duncan Phillips, making Wells one of the first Black artists to be acquired by a major Washington museum. Wells was an influential figure in Black art, as he was a mentor to some of the most well-known icons of the Harlem Renaissance, such as Jacob Lawrence and Charles Alston.

Attending Howard University’s 34th James A. Porter Colloquium on Friday, April 5, was enlightening, to say the least. As a Black woman, it was inspiring to be in the presence of so many Black women (many of whom are Howard alumni) who serve in impactful positions in major museums around the country. From curators to directors and educators alike, these women continue to break down barriers and reshape the narrative of representation in the art world.

Even though Black women are the most underrepresented in museums as employees and artists, there was no underrepresentation of intelligence, resilience, and talent present at the Colloquium. I am so grateful to witness the wisdom and knowledge of individuals with whom I share similar backgrounds have such an impact on the contemporary art world. Their presence and contributions not only reshape their art institutions but also pave the way for future generations of Black women, such as myself, to finally see themselves reflected in these once-exclusive spaces.