Decoding Victor Ekpuk’s New Installation—What Do You See?

Collection

2021-22 Sherman Fairchild Fellow Shiloah Coley speaks with Victor Ekpuk about the sociopolitical signs and symbols in his centennial commission.

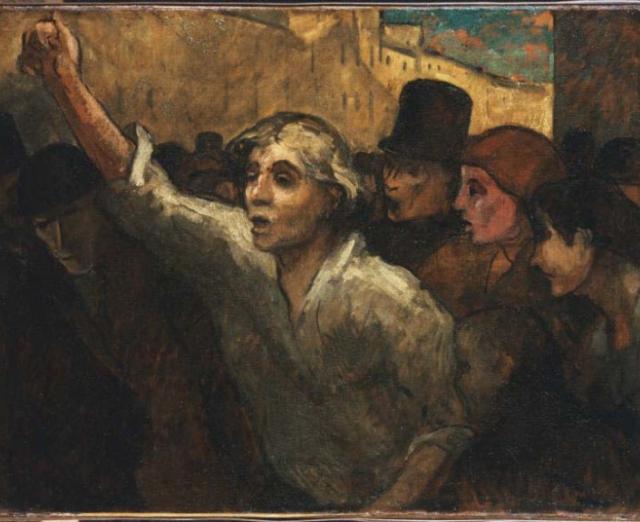

At first glance, it might appear as though Victor Ekpuk has transformed the main visitor entrance of the Phillips into a jubilant setting, switching out the old taupe color for bright white and yellow, contrasting the black marks in his installation and illuminating the space. However, one would be amiss to stop looking there—to stop seeing. The installation, State of the Union: Things have fallen apart, can the center still hold?, sets out to do something much more than simply beautifying the entryway. The title is a hint at that.

Victor Ekpuk’s new installation in the Phillips’s admissions lobby. Photo: Lee Stalsworth

The signs and symbols are indicative of Ekpuk’s reimagining of ancient Nigerian script, Nsibidi. Printed on adhesive vinyl, the script floods the walls of the museum’s vestibule, combining abstracted and representational elements. Ekpuk shared, “It’s a metaphor for America itself. America the beautiful. The America for freedom. The America of endless possibilities and so on. But then you look under the belly of America and you see all of the stuff that’s really ugly.” The piece is the first of three site-specific commissions by DC-based artists as part of the centennial celebration at the Phillips. Ekpuk is no newcomer to large immersive installations. He has had large-scale pieces in a host of other places, including Divinity, a 30 x 18-foot chalk mural depicting his signature signs and symbols, at the North Carolina Museum of Art. But to do something in the city he calls home struck him. “To be able to contribute my ideas, my thoughts, in the community that I live in … I live here, but I do so many things outside of here,” said Ekpuk. “It’s like putting a marker in my city; I actually live here, you guys,” he chuckled. Although he calls DC home, the stamp of his mother country, Nigeria, is ever present in his work. Ekpuk, a recipient of a Smithsonian Fellowship, is internationally renowned for his paintings, drawings, and sculptures, which reimagine Nsibidi to create his own unique language of abstraction. Ekpuk draws from African and global contemporary art discourse to explore the human condition. While State of the Union: Things have fallen apart, can the center still hold? is meant for everyone to consider their own narratives in the shared city, Victor offers a glimpse at his experiences through the symbols present in the work. Victor unpacked some of them with me.

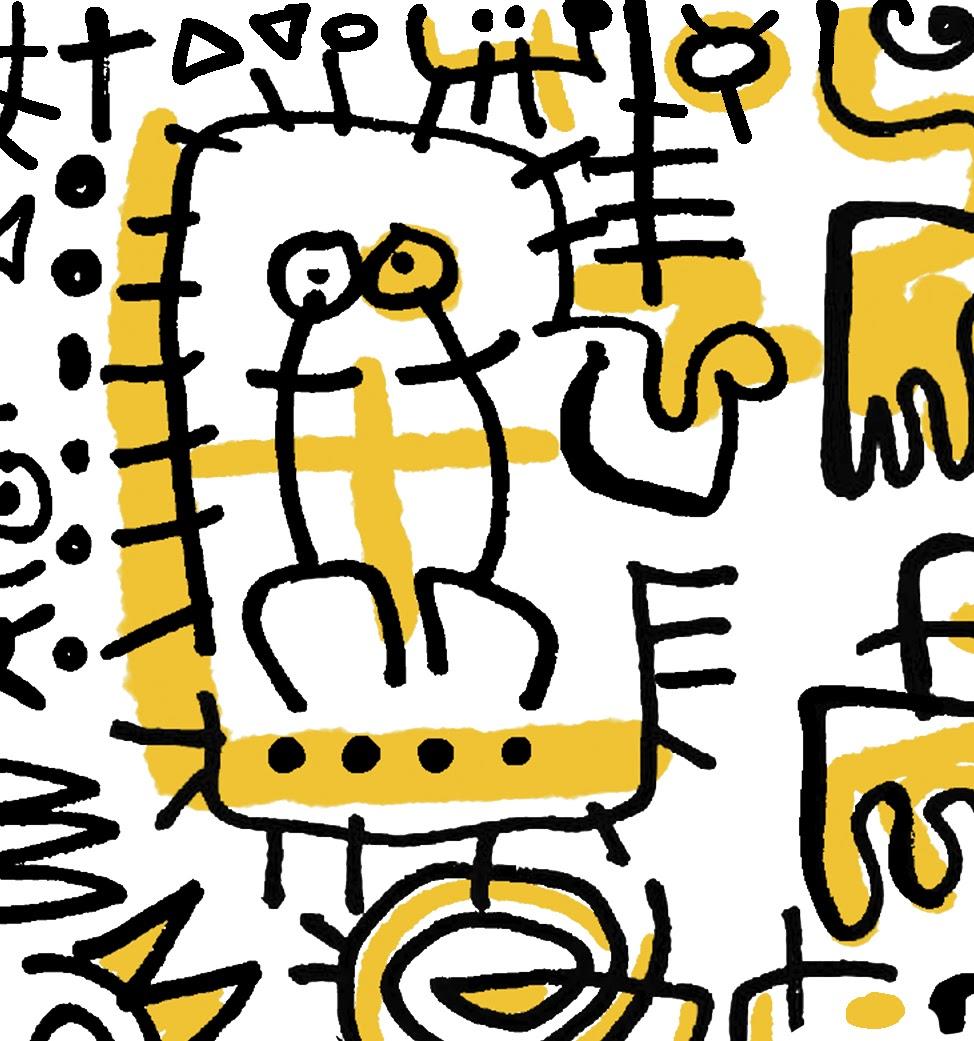

Symbol in Victor Ekpuk's State of the Union

“This symbol for many years, as Black people in America, especially as a Black male, has become a language that we have learned—hands up, don’t shoot,” said Victor. As a Black American myself, I had guessed the meaning. Although I’ve never seen one like this before, when I sat with the piece for a moment, it was as though an alarm went off indicating its meaning after a minute or so. The prevalence of police brutality, specifically in its disproportionate effects on Black communities across America, seems to have primed my brain. Victor shares a common experience many Black parents have felt: “I have an adult son and there’s not a day that I don’t worry about him when he’s out of the house.” Similarly, I worry about some of the childhood friends I view as brothers who I, too, am often concerned others might view as a threat one day. Yet, there’s the possibility of salvation in this symbol—the hand-like figure in the top left comes downward, possibly reaching toward the raised hand of the central figure—“You know, in a way maybe that’s the salvation, the savior,” said Victor.

Symbol in Victor Ekpuk's State of the Union

While the symbols serve as important reminders of the realities of the state of our union, Ekpuk also finds room for hope. “In the midst of all of this strife, I’m not giving up hope that there is no love, that people are not coming together,” said Ekpuk. “And especially for me a call for unity, because in the midst of all of this negativity there are windows of people coming together. There’s a window for love.” The two gender-neutral figures kissing is a testament to the human condition, a call for love perhaps. Victor noted the nation can’t work if we don’t come together as a people. Victor hopes the piece invites others to think about their narratives and how that influences how they interpret the symbols, and if they choose to give the work a better look—to try to see. When you visit the piece at the main visitor entrance, please share with us on social media the symbols you find and what they mean to you using #Phillips100.