From Otis Street: Egyptian Paddle Dolls, The Goddess Hathor, and Khener Dancers

Collection, Education & Community Engagement

Artist Cheryl D. Edwards of the Otis Street Arts Project reflects on the workshop she led: Revival of a Life: The Making of a Water Angel.

My workshop offered instructions and motivation to create Water Angels in relation to examining the sacredness of life using symbology. As background information and inspiration, I examined the history of the Egyptian Paddle Dolls, the mythology of the Egyptian goddess Hathor, and the Middle Kingdom Khener dancers. I thought that this would be a relevant creative exercise to allow participants to reflect on thoughts of restructure, restoration, and light as a pathway to life after COVID-19.

Artwork by Cheryl D. Edwards

“Paddle Dolls have been interpreted variously as concubines for the dead, as children’s toys, or as figurines embodying the concept of fertility and rebirth. Paddle dolls have been recovered from secure archaeological contexts at very few other sites and only in small numbers, but they are frequently found at Asasif.”[1] I have been using the Paddle Doll as an inspiration in my work since 2018. It all started with me looking for an organic shape to use in my ongoing series, which uses water as a metaphor to instigate discussions about identity, memory, and humanity. I am sure many of us spent hours, days, and months contemplating our lives during this pandemic. I have spent most of my time pouring these thoughts into my artwork as a way to go deeper into the work. It is necessary to understand the history of an object or person to better contextualize what one is creating in the present. Paddle Dolls were founded within the mythology of the goddess Hathor. “In the non-literate and nomadic C-Group culture of Lower Nubia, ritual and worship were not organized around a sacred text, nor were they carried out in a temple. Rather, many important rites of passage and worship were heavily associated with communal performance of dance and music. In such rituals the power of music and movement were harnessed to transport the worshipper into an ecstatic encounter with the Divine. Worshippers, engaged in nocturnal rituals for the goddess Hathor, sought this type of ecstatic encounter. It appears that the ecstatic nature of the dancing performed for the goddess and the spiritual “drunkenness” that it induced were valued in the ritual context of celebrations for Hathor: goddess of music, dance, love, and fertility.”[2] The story is that Hathor was the daughter of the god Ra. Ra died and his daughter removed her clothing and began to dance in front of her father’s body. The story concludes that this dance revived the life of her father. Hathor was not always a benevolent goddess. She was sleep induced and was carried to the river Nile and submerged into the water. She awoke and was changed; thus, such attributes as fertility, love, dance, and music were permanently part of her new character. I explained in the workshop that we should learn from this in thinking about the life of someone that we lost during this pandemic, from COVID-19 or natural death. It is important to understand that any life is sacred, and that sacredness should be acknowledged. The Middle Kingdom Khener dancers continued the legacy of Hathor. The dancers were Nubian women who performed at funeral ceremonies, as well as other celebrations. It was their mission to keep Hathor’s story and ritual alive. It was thought that if one could not revive a life with the ritual then they could refresh their soul in the afterlife. “Nubian women appear as Hathoric dancers from the Middle Kingdom (2000–1700 BCE) through the Roman period (30 BCE–395 ce). Representations of priestesses of Hathor sporadically, but repeatedly, included Nubian women dancers, singers, and musicians engaged in religious celebrations of the Beautiful One, the Gold, the Lady of Dance, the goddess Hathor… Beginning in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 BCE), Nubian women appear in Egyptian tomb and temple art that depicts banquet scenes where those women act as musicians and dancers.”[3] I spoke about color palettes, mixed media art history, and composition with one point perspective. After a further discussion about symbology which reference death―e.g., Egyptian tattoos and clappers, American symbols―we began creating our artwork. We began with our collective intent inspired by young African American poet Amanda Gorman: For there is always light, If only we’re brave enough to see it. If only we’re brave enough to be it.

Artwork by MaryAnn L. Miller

There were about 65 participants in the workshop and during our time spent creating we listened to music by Miles Davis and performances by Andrea Bocelli. After two and a half hours, the participants presented their work and spoke about their intent. I was amazed with what I saw! What struck me was the ways in which the artists embraced the concept and the history of the workshop and created work which undeniably spoke in their singular voice.

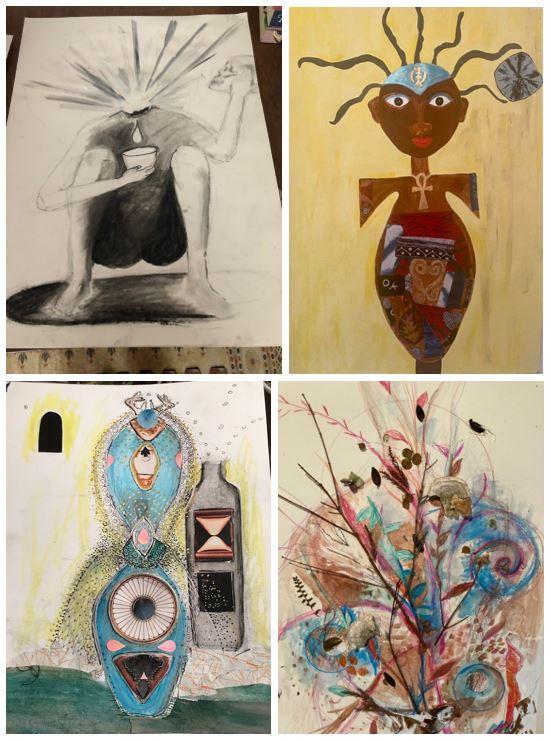

Clockwise from top left: Artwork by Shanti Norris, Donnette Cooper, Lisa Rosenstein, and Sharon Fishel

As our time together ended, I played the video entitled 8:46 composed and performed by Diane Monroe and many other violinists. In this work Diane Monroe is elevating the lives of many African Americans killed by police brutality and hate groups. As we all sat in our collective consciousness, I gave thanks to The Phillips Collection and the Otis Street Projects for giving me this opportunity. My hope is, as we move in our collective consciousness to restructure our society and the world, we will be filled with light. [1] Ellen F. Morris, “Paddle Dolls and Performance,” 2011, Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, Vol. 47, p.7 [2] Solange Ashby, “Dancing for Hathor: Nubian Women in Egyptian Cultic Life,” 2018, Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies: Vol. 5 [3] Ibid.