“Before painting, there was jazz”

Phillips Music

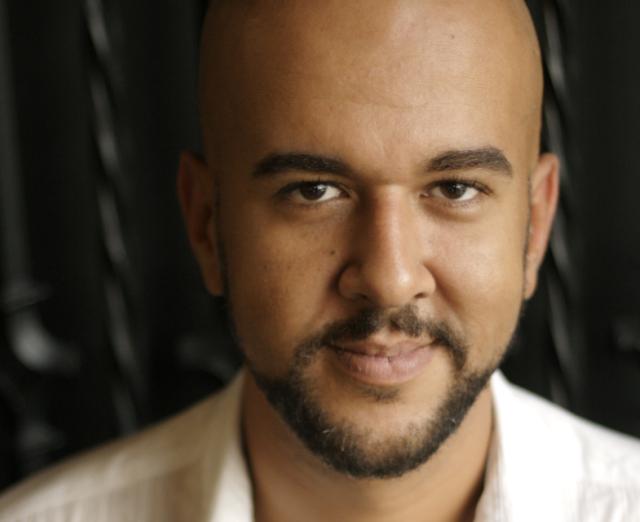

Director of Music Jeremy Ney on Sam Gilliam’s relationship to jazz. Visit our Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter August 10-30 to learn more about the intersections of art and music.

“Before painting, there was jazz.”—Sam Gilliam, 2014

Sam Gilliam, April, 1971, Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 60 in. The Phillips Collection, Bequest of Mercedes H. Eichholz, 2013

When we look at Sam Gilliam’s painting April (1971), what music might we imagine to accompany the image? In a 1985 local TV profile entitled “Sam Gilliam—Symphony of Color,” the segment producers chose an arrangement of J.S. Bach’s Air on a G String as the musical backdrop to Gilliam’s canvasses. Slow and meditative may have been the intended mood, but you are more likely to feel as if you are on hold with your insurance company than you are to be acoustically stirred by the work of this singular figure in American art of the 20th and 21st centuries.

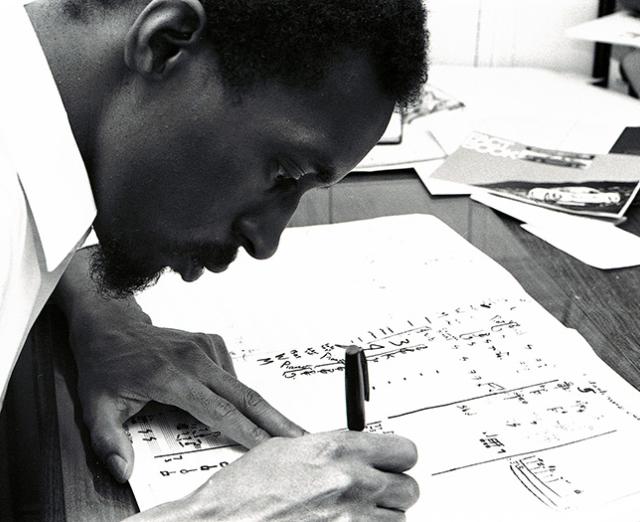

What changes about a painting like April when we think about the music that Gilliam himself loves: jazz? Gilliam has spoken frequently about the influence of jazz on his art. When he moved to Washington, DC, in the early 1960s, he promoted concerts, bringing the Modern Jazz Quartet and Marian Anderson to the city during the era of civil rights. Painting in his DC studio, Gilliam listened to the vanguards of bebop: Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, and Thelonious Monk, radical improvisers who pioneered a liberated Black musical aesthetic rooted in African and African American cultural history. Gilliam has talked about his associations with John Coltrane’s music and the aural impression of his “sheets of sound”—a conscious visual metaphor for Coltrane’s innovations in jazz harmony and rhythm. “Coltrane worked at the whole sheet,” Gilliam has remarked, “He didn’t bother to stop at bars and notes and clefs and various things, he just played the whole sheet at once.”

Gilliam has also identified with the performance of jazz musicianship, saying, “jazz leads to the acrobatics of art,” revealing his affinity with the bodily, affective presence of a musician like Coltrane in the “acrobatic” moment of improvisation. As is well documented, Gilliam remained wholly committed to abstraction in the 1960s and 1970s, at a time when the Black Arts Movement (BAM) sought to frame Black art through a “socially responsible aesthetic” that was rooted in figuration and realism. Gilliam’s abstraction allowed him to move more fluidly through questions of race and self-identity, and he chose to relate to them freely as one element among many, rather than as a matter of fate. His engagement with jazz was similar; it is not always explicit in his work, but it is central to the mosaic of his artistic identity. His statement that “before painting, there was jazz” is revealing in this context. As French philosopher Gilles Deleuze has observed about the painterly process, “It is a mistake to think that the painter works on a white surface,” by which he means that the blank canvas is already filled with the ideas that the artist brings to the painting. He calls this “the painting before the painting.” Gilliam’s decisive “before painting, there was jazz” compels us to interpret the aural trace of jazz influence in his work. The Phillips’s beveled-edge painting April reveals Gilliam’s intensely performative process, which—like jazz—requires a balance between structure and improvisation. At this time, he applied paint freely to canvases placed on the floor, folding the material while the paint was wet, a procedure that introduced improvisatory elements to the final composition. The title, April, signals a conceptual link to earlier paintings, April 4 (1969) and Red April (1970), both of which refer to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King (April 4, 1968), rooting the multiple April paintings in a shared, humanistic social consciousness. In 1971, Gilliam also produced Lady Day, an explicit homage to jazz singer Billie Holiday, which shares the same coloristic, sensuous lyricism as April. While the titles of the canvases flag their social, political, and cultural concerns, these are also rendered ambiguous through the process of abstraction. Within Gilliam’s process of defamiliarization through abstraction, he found a model in the experimental attitude of the practitioners of bebop, who recombined and transformed the elements of jazz through a process of hybridization and synthesis that created a new art form focused on individual freedom and agency. The radicalism of artists like John Coltrane formed the perfect analogue for Gilliam, who sought a similar individualistic style unconstrained by disciplinary boundaries. So when Gilliam refers to himself as “more like a composer,” as he does at the beginning of the 1985 TV interview, we should think critically about how to interpret musical influence in his art. We might be cautious not to frame the metaphor of Gilliam the composer through the prism of Eurocentric Western art music, typified by a “universal” figure such as Bach, but engage with the musical culture and influences closest to the artists’ life and work. Such an engagement may reveal different layers of interpretive depth to a painting, sparking the questions: can music transform what we see, and could a work of art help us hear in new ways? To confront such an intersensory provocation, we would do well to heed the words of jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker, who encouraged his audiences to “hear with your eyes and see with your ears.”

Adapted from the forthcoming catalogue Seeing Differently: The Phillips Collects for a New Century (D Giles, 2021), published on the occasion of The Phillips Collection centennial.