I Miss Ben Shahn's Still Music

Collection, Phillips Music

The Phillips Collection galleries have been dark and empty and our staff and visitors have been missing our beloved collection. In this series we will highlight artworks that the Phillips staff have really been missing lately. Director of Music Jeremy Ney on why he misses Ben Shahn’s Still Music (1948).

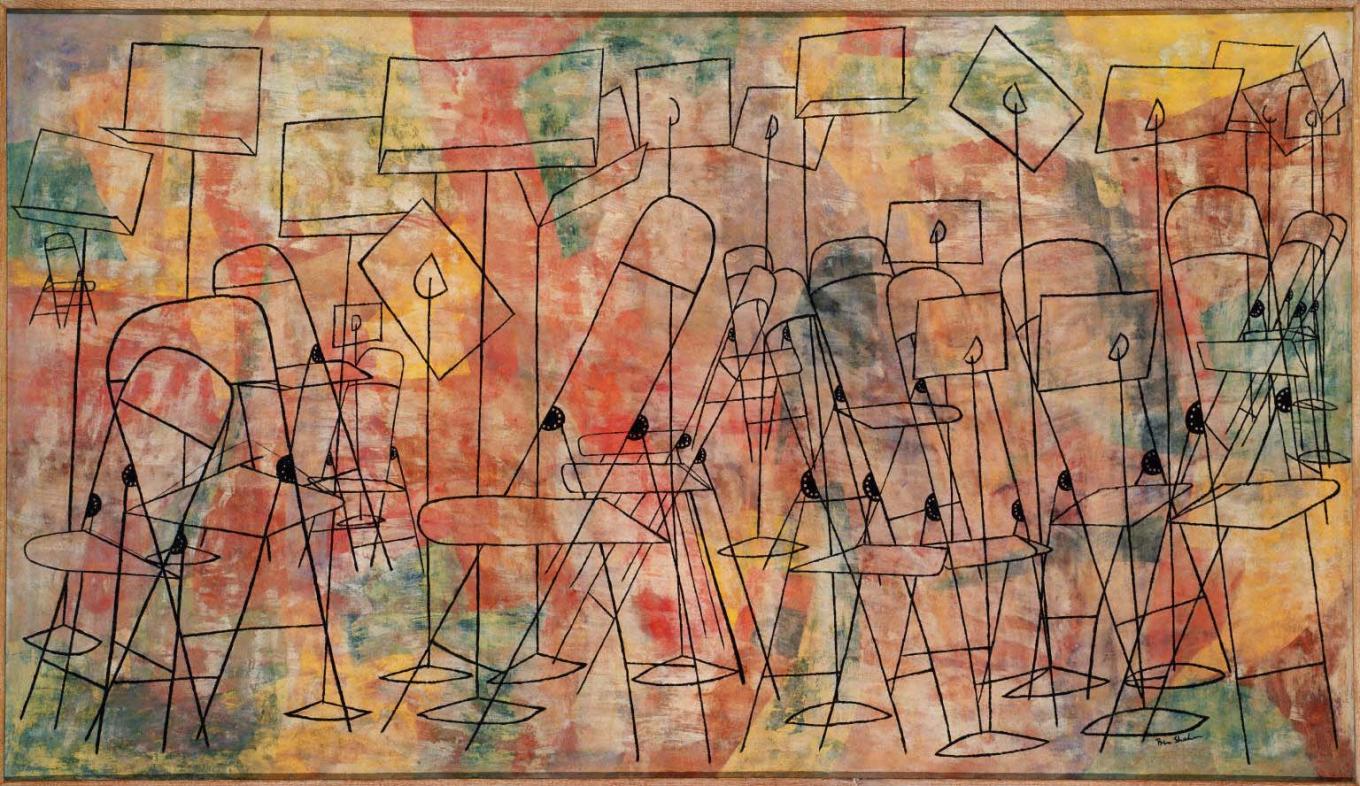

Ben Shahn, Still Music, 1948, Casein on fabric mounted on plywood panel, 48 x 83 1/2 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1949

Earlier this year, before we temporarily closed our doors, Ben Shahn’s 1948 painting Still Music was exhibited on the second floor of the Phillips House next to the Laib Wax Room. The juxtaposition was intriguing; sight, scent, and sound inhabiting the same proximity. However, one sense was noticeably absent from the equation; music appeared as a silent partner in this particular synesthetic exchange. Ben Shahn produced several works on this visual theme; along with the Phillips’s painting, there are later screenprints that share the same precisely controlled graphic elements of disordered chairs and strewn music stands, albeit with the modified title Silent Music. “Still” or “Silent” the effect seems to be the same; painting “music” has the curious visual consequence of robbing music of its material ability to sound, to be audible.

However, I like to think that the title is more of a playful provocation; looking at the bold horizontal and vertical lines (with their echoes of Paul Klee’s art, one of Shahn’s favorite artists), there is nothing still about the image—it is in fact highly animated. There is a dynamic interplay between the gradations of background color as one element, and the rhythmic, angular lines as another. The effect is similar to what we see in Klee’s work—polyphonic and conversational—and the relationship between the painting’s form and its content creates a particular sense of latent energy. This is what fascinates me about the painting, how it communicates a direct emotional impression that opens up many different layers of possible interpretation. Duncan Phillips saw in Still Music the “vibrations of music one senses during the intermission in a concert,” whereas Shahn was more tongue in cheek, suggesting that the absent musicians of the scene had gone on strike—“local 802 on strike!” The stark difference between the two interpretations only works to enhance the mystery of the image.

Taking up Shahn’s implicit invitation, my own interpretation is closer to Duncan Phillips’s, seeing in the idea of stillness an analogue to that particular moment in musical performance just after the last sound dissolves, where time feels temporarily suspended. As our Music Room falls silent for the foreseeable future, Still Music reminds me of the energy of that moment of live performance and makes me wonder how that same energy can live in paintings, too.