Music, Symbolism, and Les Nabis

Phillips Music

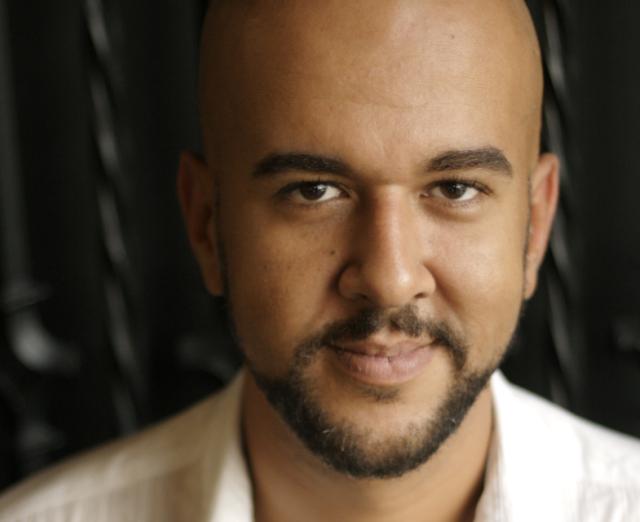

Between November 2019 and January 2020, Phillips Music presented three concerts exploring the interrelationships between music and art in the period of the Nabis as part of the exhibition Bonnard to Vuillard: The Intimate Poetry of Everyday Life—The Nabi Collection of Vicki and Roger Sant (on view through January 26). Ahead of the last of these performances on Sunday, January 12, featuring resident musicians from the Queen Elisabeth Music Chapel in Belgium, Director of Music Jeremy Ney reflects on some of the cross-disciplinary currents that united visual artists and musicians in the late 19th century.

“Think…of the musical role color will henceforth play in modern painting. Color, which is vibration just as music is, is able to attain what is most universal yet at the time most elusive in nature: its inner force.”—Paul Gauguin, 1899

In 1884, Symbolist poet Paul Verlaine made a curious statement about the future of poetry in his publication L’art poetique. He wrote that poetry should seek to become “music before all else” (“De la musique avant toute chose”). This seemingly radical idea compelled the artists of his generation to look to the example of music for the formulation of new aesthetic directions for art. If it seems unusual that Verlaine would seek to devolve his art form from its own resources in the search of something completely new, his talismanic statement on the value of music for all art was, by the 1880s, surprisingly a rather commonplace idea. Baudelaire, under the influence of Wagner’s music, had opened the flood gates in the 1850s through the concept of synesthesia and correspondence between the arts, emphasizing the value of music for its non-imitative, abstract capacity. Before this, artist Eugene Delacroix discussed his paintings in musical terms as early as 1824. Coining the idea of the “musicality” of painting, Delacroix used the example of music to show how a work of art could transcend imitation to achieve a higher aesthetic goal. Influenced by Baudelaire and Delacroix, Paul Gauguin sought to infuse painting with the powerfully affective, mysterious aura of music, suggesting that in painting, “ultimately we should look more for suggestion than description, as with music.” Gauguin also espoused rational, scientific parallels, describing color as “vibration, just like music,” unifying an idea prevalent in the Renaissance (the Pythagorean theory of the Harmony of the Spheres, that mathematical intervals linked musical sounds with the divine) with new concepts about the science of color; that colors could be arranged in scales with “consonant” and “dissonant” harmonies (foreshadowing the color theories of painter Wassily Kandinsky, or the musical color wheels of composer Alexander Scriabin). As Gauguin sought to move beyond traditional figuration into what he described as “mysterious centers of thought,” it was the example of music—both for its vagueness and mystery as well as its scientific, rational properties—that helped free painting from the strictures of representation, supporting a trajectory that would lead, ultimately, to abstraction. Gauguin’s ideas and teachings were hugely influential to the artists of the Nabis. Vuillard, Denis, Bonnard, and other painters of the Nabis adopted Gauguin’s ideas of the sensory and emotive capacities of color and form, and their wider intellectual engagement with literary symbolism (through the writings of Baudelaire, Mallarmé, and Verlaine) meant that they also fully absorbed the principles of correspondence, synesthesia, and the musicality of painting. Of all the members of the group, Maurice Denis was the most profoundly influenced by music and musicians. Denis’s understanding of music informed his theoretical writings (notably in his influential treatise of 1890, Définition de néo-traditionnisme), and he established close links with the musical milieu of his time. He was friends with Claude Debussy, collaborating with the composer on lithographic covers for his scores, and he was close with the circle of devotees surrounding César Franck, particularly Ernest Chausson, with whom Denis formed a close personal friendship. Intellectually, Denis was aligned to the Franck school’s guiding principles of la musique construite, and the desire to liberate French music from the accreted excesses of late-German romanticism by re-introducing the order and structure of forms drawn from renaissance and early-classical music. In his theoretical writings, Denis articulated a parallel ambition for painting and the decorative arts, hoping to orientate the Nabi group toward a revived classicism. Compared to other members of the Nabis, Denis had a much deeper grasp of music, and while others may have subscribed to the general concept of music as abstract, suggestive, mysterious, or atmospheric (profoundly Symbolist qualities), Denis saw in music more formal ideas and structures that could be recognized to have analogous relationships to new techniques in painting. Denis’s highly distinctive musical tendencies are well-evidenced by his painting Les Musicians, on view in the exhibition.

Maurice Denis, Les Musicians, c. 1895. Oil on cardboard, 9 5/8 x 13 5/8 in., The Phillips Collection, Promised gift of Vicki and Roger Sant.

Nominally representational in the sense that we see four figures around a piano in the act of music-making, the painting is notable for its abstraction. Facial features are withdrawn, and sheet music is emptied of its symbols of notation. The painting instead holds the suggestion of music, the aura of its imminence. Denis deliberately draws our attention to the materiality of the line, the “rhythmic” contours of decorative Arabesques, which become the visual equivalent of an elapsing “melody” within the composition, with a concurrent “harmony” and “sonority” in the surrounding colors. If such heuristic devices feel nothing more than confused metaphors for us today, they were anything but to Denis and other creative artists in the period of the Nabis. However, the correspondences, parallels, and associations espoused by artists of this time should not be taken too literally; neither the painters of the Nabis nor the composers of the period desired a musical-visual equivalence—a transposition from one art form into another (which they saw as mere empty formalism)—but rather the burgeoning period of artistic exchange in the 1880s and 1890s provided artists and composers with the intellectual basis with which to borrow resources, concepts, or material means from different artistic domains. This Sunday’s program, conceived in partnership with the Queen Elisabeth Music Chapel and its resident musicians, presents a special confluence of currents within fin de siècle art and music. The spirit of the program is embodied—to some degree—by a single, revolutionary figure: Belgian violinist and composer Eugène Ysaÿe. Ysaÿe was a prominent musician in the cultural milieu of the late 19th century and the pre-eminent virtuoso of his age. A champion of new music, Ysaÿe was aligned with the Franck school, and he regularly toured music by Franck, D’Indy, Chausson as well as Debussy (frequently in concert with the music of Bach) internationally as talismans of French cultural export (both Franck and Ysaÿe were Belgian natives who became naturalized French citizens). As a musician, Ysaÿe came to embody 19th-century perceptions of the transcendent power and mystery of music, and in this heady period of synesthetic connection, Ysaÿe’s performances were often interpreted in lofty, poetic terms. Following a performance at Auguste Rodin’s atelier in Paris, French author Camille Mauclair described the violinist as a “living Rodin” in his novel La Ville Lumiere, thus transfiguring Ysaÿe into the solidified permanence of a museum piece. The exchange went both ways, and Ysaÿe took an active interest in other art forms himself. In 1894, he programmed a series of four concerts with the Ysaÿe Quartet at the Musée de l’Art Modern in Brussels during an exhibition curated by Octave Maus titled La Libre Esthétique (The Free Aesthetic). Ysaÿe created an ambitious series of concerts that were ideologically aligned to the “Franckistes.” The second concert featured an all-Debussy program in which the String Quartet in G minor, Op. 10 received its second performance (the premiere had taken place at the Société Nationale in Paris in 1893). The final performance presented Chausson’s Concert for Violin, Piano, and String Quartet in D Major, Op. 21. Hanging in the galleries as these works were heard were paintings by Paul Gauguin, Maurice Denis, Odilon Redon, Paul Sérusier, Paul Ranson, and many other artists of the Symbolist milieu. This Sunday’s concert thus presents an irresistible opportunity to hear some of the music that was most alive to the cross-disciplinary artistic spirit of the time.

—Jeremy Ney, Director of Music