In Conversation with Los Carpinteros (Part I)

Exhibitions & Events

Los Carpinteros (Marco Castillo and Dagoberto Rodríguez) is an internationally acclaimed Cuban artist collective best known for merging architecture, sculpture, design, and drawing. Through two films and a group of sculptural portraits, Los Carpinteros’s exhibiton Cuba Va!, produces a social landscape of Cuba’s modern history that has been at once utopian and dystopian. As part of the Phillips’s Intersections series, the project is on view through January 12, 2020.

In this two-part series, Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Vesela Sretenović discusses Cuba Va! with the artists.

Los Carpinteros with part of their Intersections installation Cuba Va! (2019). Photo: Carl Nard

VESELA SRETENOVIĆ: This project has been four years in the making, and we went through a number of revisions. Meanwhile, last summer, in 2018, Los Carpinteros dissolved, and you, Marco and Dago, decided to pursue separate careers but also to show your works that were conceived and produced as a collective. Together, we agreed to move forward and complete what we started years ago and make this exhibition happen. In this sense, its title, Cuba Va!, is emblematic not only of Cuba, but also of Los Carpinteros now, no?

LOS CARPINTEROS: Cuba Va! is an ironic title because the situation today is the opposite—Cuba is not going anywhere. Cuba is no longer a revolutionary, progressive place, but a place of stagnation, a place to be and survive…On the flip side, the exhibition title sends a message of hope for the future, for both the country and for us, the collective. Los Carpinteros will continue to showcase and publish artworks in order to preserve its legacy—26 years of collaboration—for posterity.

But back to the title itself. Cuba Va! derives from a popular song from the early 1970s written and produced by the Experimental Sound Collective. At the time, it was an experimental and emotional song in terms of both melody and lyrics. The sound is very repetitive, somewhat inspired by the rock-and-roll of the Beatles, but mixed with salsa, while the words echo hippie optimism, the pop aesthetic and spirit that were positive at heart and promising of “a new man” that is the new social order.

Left to right: It's not Che, It's Simón (2017); It's not Che, it's Eusebia (2018); It's not Che, it's Alfonso (2018); Cachita (2013). Photo: Carl Maynard

VS: Let’s start with the portraits. Seven are on view: Cachita, René, Isabel, Eusebia, Simón, Felicia, and Alfonso. Cachita, along with Emelino, were the first ones created, in 2013. They were very personal—Cachita was made after Dago’s mother and Emelino after Marco’s grandfather. Then there was a gap of a few years between them and the rest.

LC: The idea behind the first portraits was to tackle the notion of heroism, or rather to question what constitutes heroism and who are the real heroes. Here we focused on the generation that aged with the Cuban revolution itself, including our relatives. At the same time, we made portraits of internationally renowned political figures such as Angela Merkel, Noam Chomsky, and artist Santiago Sierra, who were all critical of high capitalism. The recent portraits created for and presented in this exhibition return to the original idea of portraying ordinary Cubans who carried out the weight of the daily struggle in Cuba and who are the real heroes. Now many of them live in asylums and nursing homes where the care is very poor; they fought for the ideals of equality only to be forgotten in poverty—very sad!

VS: What were you looking to capture in these portraits?

LC: Aged faces, a map of wrinkles that trace hardship but also beauty. They are heroes not of the revolution, but of life, endurance, and survival.

VS: And how did you come up with their titles: It’s not Che, It’s Isabel or It’s not Che, It’s Simón, etc.? LC: We were first using only the names of real people, but then we realized that that’s not enough, that we were missing the link to the concept of heroism. The idea came from an article that was referring to the Merkel portrait, saying, “It’s not Che, it’s Angela.” We read this while we were in Greece exhibiting our portrait of her. And that was it—something clicked right then!

VS: Tell us more about how you made them. Was it an elaborate process?

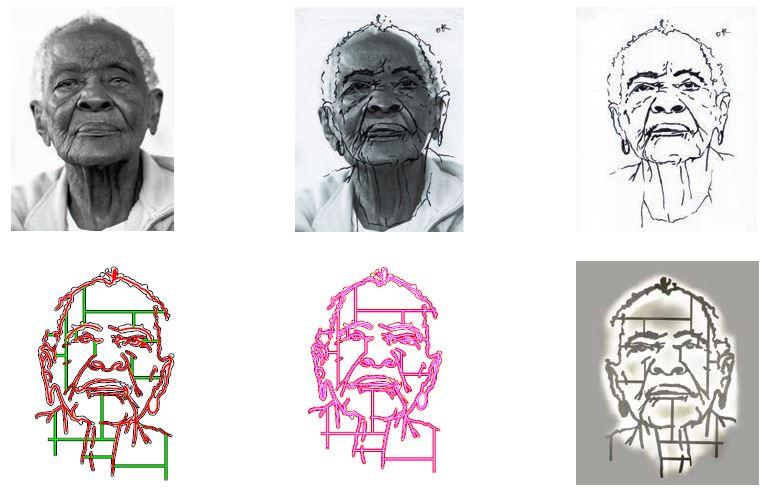

The process of rendering the portraits based on photographs by Leonardo Feal. Courtesy of the artists.

LC: Yes, we tried to follow the steps of Enrique Avila, author of the sculptural portraits of Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos located in the Plaza de la Revolución in Havana. He worked from the famous photographs of Che taken by Alberto Diaz (Korda), so we called Leonardo Feal, a contemporary Cuban photographer, to work with us on this project, thinking of him as the Korda of our time. We went together to visit old people’s homes, nursing homes, asylums, and also places where they would congregate, like the May 1 parade (International Labor Day). We amassed a large group of photos from which we selected seven. Feal’s photography has the great power and sensitivity in conveying facial expressions that we were looking for and it served as a basis for developing our sculptural portraits. From there on, we alternated between hand-drawn and digital processes in order to simplify the photographic image.

The Plaza de la Revolución in Havana by day and night, with portraits of Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos.

We faced a lot of technical problems because digital design tends to generate cold-looking images and we wanted revealing faces. Therefore, we went back and forth numerous times until we achieved a desired appearance. Then, we had to work on the grooves where the LED light cables were going to be placed and balance that with the drawn lines that capture the personality of the portrait. This was another big challenge that we had to work out with our fabricators. After many lighting tests, we finally got our glowing portraits. For us, they function like domestic monuments; they are personal and commemorative, humble and heroic.

Stay tuned for Part II of the interview about the films in the exhibition.

Read the full interview in the Los Carpinteros: Cuba Va! catalogue, available in museum shop.