The Beethoven Effect

Phillips Music

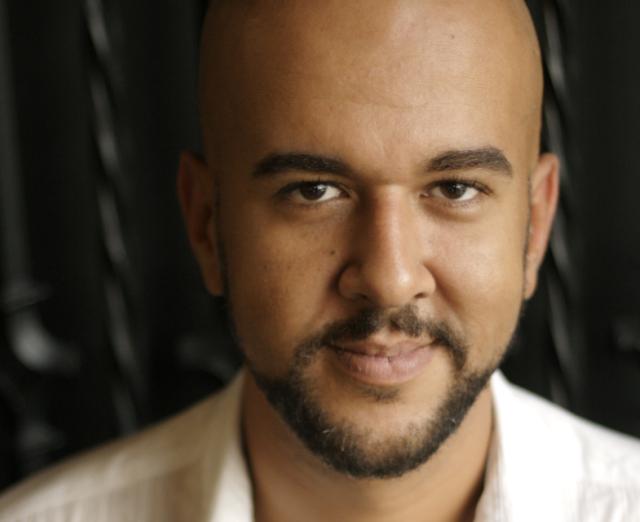

Ahead of pianist Jonathan Biss’s first Sunday Concert (November 3) in a three-concert series exploring the Piano Sonatas of Ludwig van Beethoven during the 250th anniversary of the composers birth, The Phillips Collection’s Director of Music Jeremy Ney reflects on Beethoven’s legacy at this milestone year of celebration.

The 2019/20 season marks the 250th anniversary of the birth of Ludwig van Beethoven, the most well-known and most admired Classical composer in the history of Western music. Beethoven’s status within culture is something akin to ubiquity; not only is his music performed more than that of any other composer but some of his works have made unusual symbolic leaps into broader cultural, political, and social spheres. Beethoven is the composer we turn to in moments of national crisis (as with the performances of the Ninth Symphony after the September 11 attacks), and the composer of unity, hope, and humanitarianism (the Ode to Joy from the Ninth Symphony is the anthem of the European Union, and as recently as October 25 this year, the Ode was sang in Arabic by Lebanese protesters in Beirut). Indeed, the “Beethoven effect” can be traced in all manner of seemingly disparate fields of activity across time, from 18th-century philosophy to 21st-century film and pop culture, which says much about the adaptability of the Beethovian image and the enduring power of his music.

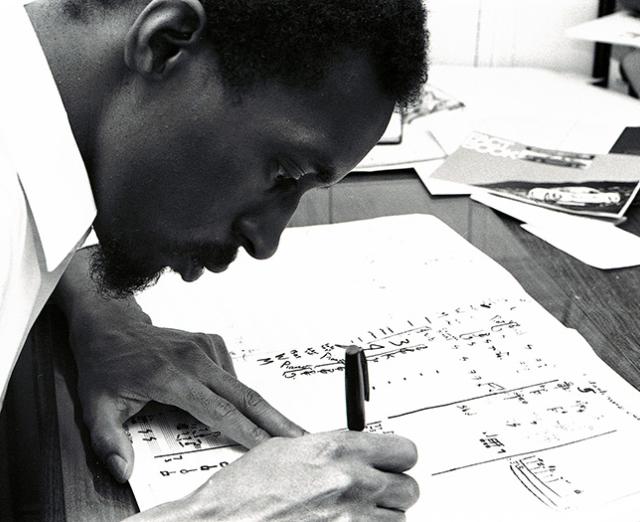

Illustration by Kathryn Zaremba

Yet the monumentalizing of Beethoven’s genius is not new; it began in his own lifetime, and his trajectory from earthly musician to transcendent musical prophet closely paralleled a shift in the perceptions of music itself. In the years after 1800, music as a practice both in performance and composition became less dependent on court appointments or church practices. The proliferation of public concert halls in the early 18th century democratized the experience of musical performance, whilst the philosophy and aesthetics of enlightenment thinkers such as Kant or Schlegel raised music’s status to that of the highest art, capable of speaking a truth beyond words, reason and concepts. Musicologist Mark Evan Bonds has observed that at the dawn of the Romantic era, the composer became “an oracle who speaks in tones that cannot be translated into words: rhetoric gives way to revelation.” In this context, Beethoven became the paradigm of the “liberated composer,” his music imbued with a metaphysical transcendence that was beyond the vagaries of the mundane world. As a means to interpret and understand this new revelatory power of music, new modes of poetic and descriptive written criticism proliferated. The influential writings of E.T.A Hoffman (which were published in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung) made Beethoven’s putative claim to the sublime clear: In his 1810 review of the Fifth Symphony, he writes that Beethoven’s music “opens to us the realm of the monstrous and immeasurable. Glowing rays shoot through the deep night of this realm, and we sense giant shadows surging to and fro.” Within Beethoven’s chamber music, some of his piano sonatas gained nicknames such as “Moonlight” and “Pathétique” (added by critics and publishers), which lent opaque, suggestive, and poetic visions to the music. The practice of bestowing music with extra-musical allusion would have a long history after Beethoven but it began with his example. Long after his death, these fragments of history and biography stick to the mythology around Beethoven, both enriching and complicating our relationship to his music. Assessing Beethoven’s legacy does not necessarily mean stripping back the excesses of Romantic-era thought, or returning an earthly, mortal image to this most immortal of composers. The 250th anniversary represents an opportunity to view the composer in his totality, celebrating the scope of his achievement in music, and his singularity as a figure in the history of art. He was one of those rare characters who both seized the spirit of their own epoch and left a body of artistic work that has only grown in popularity since his death. As the conductor Andris Nelsons has observed, Beethoven’s music is “for our time and all time.” The Piano Sonatas Within the many musical forms that Beethoven revolutionized, his achievement within the 32 piano sonatas represents something completely unique in his output. Generally split into three distinct periods, they exemplify the shift into early Romanticism, as Beethoven developed from the relative simplicity of the classical style in the first few sonatas, to the greater harmonic innovations and emotional complexity of the monumental final three sonatas of Op. 109, Op. 110, and Op. 111. For any pianist, recording the 32 piano sonatas is akin to summiting a (crowded) musical Mt. Everest. Yet it is an Everest that demands maturity, patience, and vision, as much as youth and ambition. In recent years, the acclaimed American pianist Jonathan Biss has brought such a balanced approach to his recording of the complete cycle, a process that began in 2011, and will conclude in 2020 with the release of the full box set. During Biss’s nine-year odyssey into recording the music of Beethoven, he has published an e-book about his experiences called Beethoven’s Shadow, and launched an online course exploring all 32 Piano Sonatas in collaboration with the Curtis Institute of Music. In the 2019/20 season, Biss performs full cycles of the sonatas worldwide, including performances at The Phillips Collection on November 3, December 1, and March 22 to explore sonatas from Beethoven’s middle and late periods respectively.

-Jeremy Ney, Director of Music