Ranjani Shettar: Making Earth Songs

Collection, Exhibitions & Events

This spring, the Phillips is excited to present Ranjani Shettar: Earth Songs for a Night Sky as part of the Intersections contemporary art series. In February 2019, Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Vesela Sretenović visited Ranjani Shettar at her studio in Karnataka, India, to look at and discuss her work and inspiration.

Join Ranjani and Vesela for a conversation at the Phillips on May 16 at 6:30 pm.

Ranjani Shettar and Vesela SretenovicÌ discuss an installation in progress in her studio.

VS: Let’s start with the title for your upcoming Intersections project, Earth Songs for a Night Sky—where does it come from?

RS: My titles mostly happen toward the end. At the beginning I have a general impression of the show and as the works are being made the vocabulary develops slowly and the title comes from there, gradually. In this case, the title came from my daily life, my surroundings, the jungle and the sky, but it’s also universal in a sense that when you live in a remote place like I do, you experience things in solitude, more vividly and closer to their natural habitat. Here I wanted to create something light, melodic, and joyful, something like when you sing a song with your heart and you are happy! Of course, there are so many things that are not right in this world and I do want to take them into account, but I am a person full of hope and I want to emphasize the state of hopefulness and the positive aspect of things.

VS: “Songs” in your title brings to mind Kandinsky’s Klänge (in English Sounds), his 1913 book of poems and woodcut illustrations. Your works seems to me like a dance to Kandinsky’s “sounds.”

RS: Perhaps, but Kandinsky calls for sounds, and I call for songs. For me, sounds and songs are different things. A sound can be anything, while as song is about synthesized sounds; in other words you chose sounds to make a song. And then you sing a song! Kandinsky’s words and images are sounds, they are simple and I love his visual poetry.

VS: Your creative process is extremely laborious, and you love it. Earlier you said that the meaning is in the process. How so?

RS: Well, so much happens in the process of making; there is a lot of practice behind a concept, and it is this ongoing engagement on a daily basis that is the most fulfilling, more so than the final product. The slowness of making and exploration of materials matters greatly, and what comes out of that is a slow growth, which is what interests me the most.

VS: And where does your process start? with sketching? drawing?

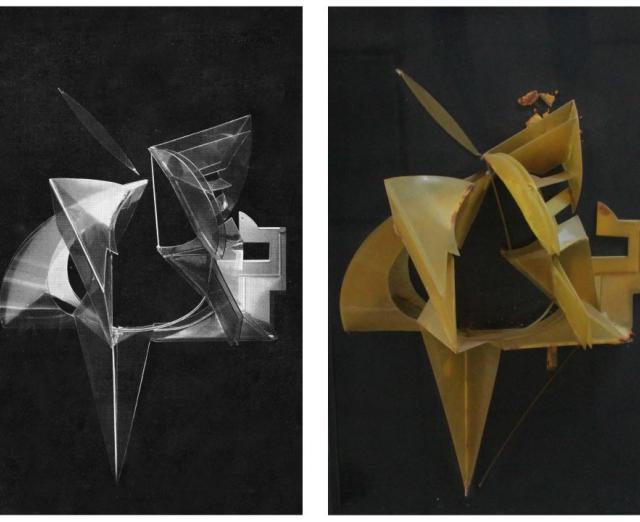

RS: It starts in the mind, but parallel with the material. I think of it as two-way. As a sculptor I am attached to my materials but also to the form, something that wants to come out. My mental image is projected over a material and the process connects the two. The hardest part of the process is when I am not doing anything physically, when I am thinking and getting ready to start. But once I start working it is the happiest time and I don’t want it to end. There is a lot of problem solving and decision making during the process of making, some are conceptual, but most are technical problems. I enjoy the hands-on, trial-and-error aspect of the process very much.

VS: Given the interconnection of process and materials, tell us more about your choices of materials?

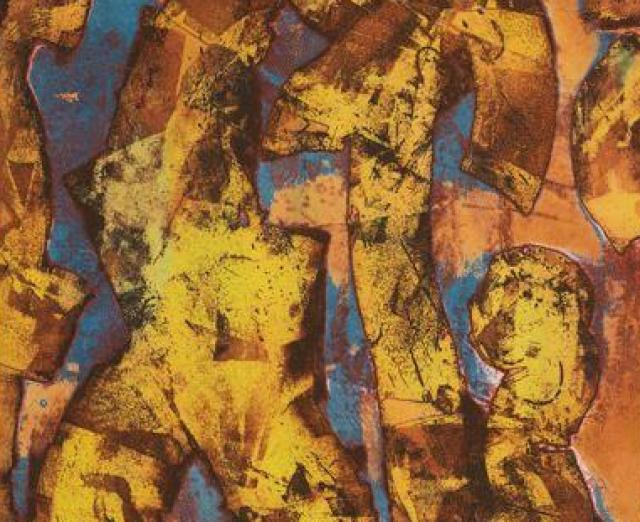

RS: At the beginning I would try out everything that I could lay my hands on. I would hop from one material to another, always learning something new. But with time I realized that the wider my choices were, the harder it was to be ecologically sensitive and responsible. I used paper, plastic, industrial materials, glue, just about anything. Now I have narrowed down my choices and work primarily with organic materials such as wood, fabric, treads, pigments, and beeswax.

Ranjani Shettar looking at an installation in progress in her studio.

VS: Where does your work come from? What motivates it?

RS: My work comes from a need to express what I imagine rather than what I see or feel—it is about imaginable possibilities of the physical world and its moving forces. I think what motivates it is three-dimensional form. The form usually comes from within the mind but also from the natural world and surroundings, like geometric forms which I then try to transform into more organic shapes. I am drawn to things that can stretch and bend, that are pliable or mutable. Subsequently, this elasticity informs the final form.

VS: Were you always drawn to abstraction?

RS: No, I started with more representational forms but slowly broke away from that. My training was in figurative art but I was never interested in objective renderings. I was drawn to pure form more than anything. And I have always loved sculpture—three-dimensionality, materiality, volume, space—rather than flat surface.

VS: Your versatility of techniques and craftsmanship is impressive.

RS: I love learning different crafts and new skills. I love design and making nice looking objects. I don’t like to have assistants—the pleasure is in the making and I want to keep that pleasure to myself.

VS: And what happens when the project is done? Does it feel empty?

RS: You see, emotional connection to my work is also very important to me. Over the years I learned to always work on multiple works at once and leave some works incomplete. That way I have something to return to—an emotional anchor!

Visiting an indigo dyeing and weaving workshop.

VS: Let’s talk about the Phillips project … still in process as we speak but coming to its completion soon.

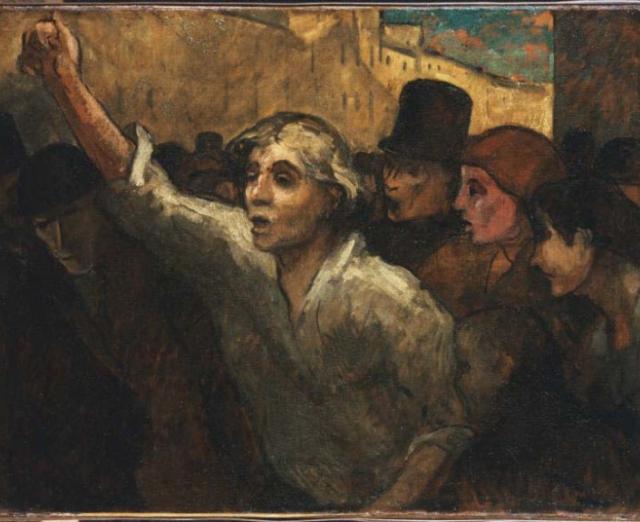

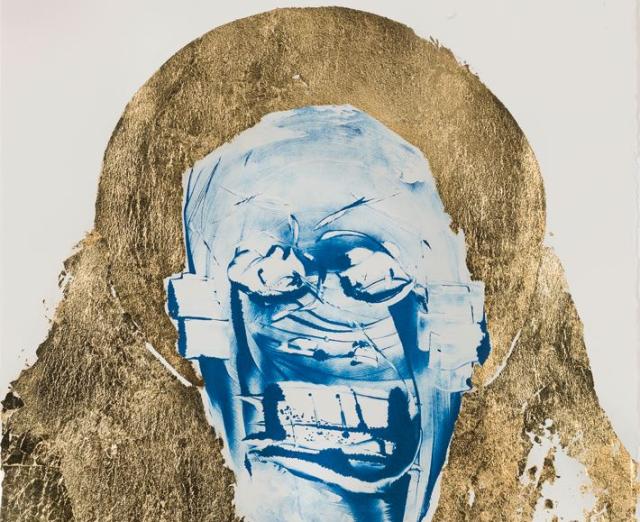

RS: When you invited me to visit the site in order to propose the project, I spent some time walking around and found the galleries in the historic house very intimate, domestic, cozy, and I liked that feel very much. And the wall that divides the two adjacent galleries on the second floor was very interesting to me. Then I thought to create a works that wraps around it—thus responding to the specificity of the architecture—directing how one navigates through the space. That particular piece, comprised of many parts, is made of stainless steel, muslin fabric, and indigo. But instead of dying my fabric, which I have done in the past, here I use indigo as paint for the first time. Being at the Phillips I saw clearly in my mind that the piece ought to be in blue; indigo blue presented itself as a great contrast to the monumental 19th-century architecture with fireplaces and their wooden mantels.

VS: But then, next to this fluid multi-part work in fabric and indigo, we have dense, wooden sculptures, beautifully carved. How do they relate to each other?

RS: For me, it is about a spectrum. If you are a singer singing in three different octaves, you read the notes together to strike an emotion and create harmony. So it is about spectrum or the “whole” made of parts.

VS: Speaking of the whole and the parts, the third part/octave of the project is a small installation made of thread and wax. Tell us more about it.

RS: Well, the three parts—fabric pieces, wooden sculptures, and thread-wax installation—are deeply interconnected. They all deal with balance and precariousness yet in different ways. They all embody volume and lightness, movement and shadow … they all occupy our living space.