On "Precision" in American Art

Exhibitions & Events

University of Maryland-Phillips Collection Postdoctoral Fellow Dr. Ashley Lazevnick muses on the term “precision” in American art. Hear more from Dr. Lazevnick at the Phillips on May 9 at 6:30 pm.

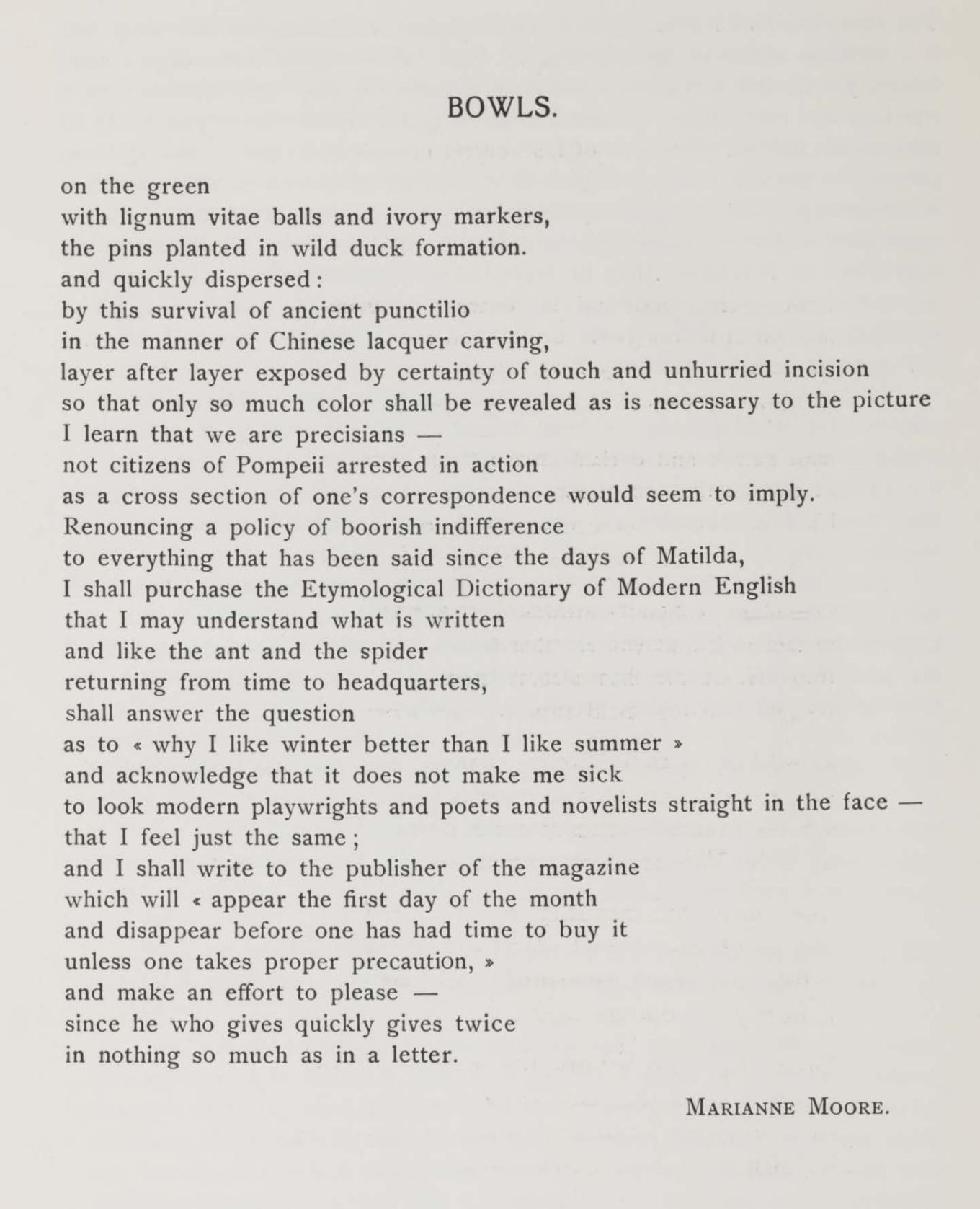

Fig 1: Marianne Moore, âBowls,â Secession, vol. 5 (July 1923): 12.

“I learn that we are precisians,” Marianne Moore confessed within the un-metered matrix of her poem “Bowls” in 1923 (Fig. 1). Famous for her strategies of appropriation and compression—which resulted in poems that were palimpsests of literary, artistic, musical, and popular cultural references both well-known and obscure—Moore crafted “Bowls” from a bricolage of associations: a bygone lawn game, Chinese lacquer carving, the ruins of Pompeii, and a magazine questionnaire. My particular interest in this poem began with a change that Moore made in 1951, when she substituted “precisionists” for “precisians.” Ever since, the poet has been tied to an early-20th century artistic movement known as Precisionism.

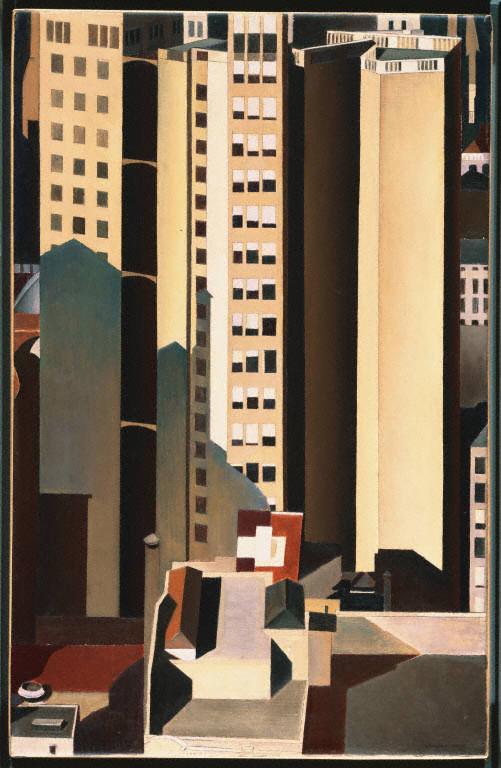

Fig 2: Charles Sheeler, Skyscrapers, 1922, Oil on canvas, 20 x 13 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1926

Recognized today for meticulous pictures of deserted factories and skyscrapers, Precisionism is exemplified by several artworks in The Phillips Collection, especially Charles Sheeler’s Skyscrapers (1922, Fig. 2) and Ralston Crawford’s Boat and Grain Elevator no. 2 (1941-2). But this was never a movement in the usual sense. There was no manifesto or exhibition or salon that bound the artists together, and even the term “Precisionist” came later (canonized in 1947 by Wolfgang Born). What makes Moore’s revision so special, I learn that we are precisionists, was her belated allegiance to the group…if by no other means than words alone. With Moore as the catalyst, my research into Precisionism delves into the history and associations of that crucial term: precision. Up until now, the movement has been aligned with mechanization and mass-production, but I am interested in its unexplored connection to precision in poetry and philosophy. What does it mean to create a “precise” work of art? Where did “precision” show up during this period? And what were its meanings?

Fig 3: Advertisement for Kroydon Clubs, New York Times (July 22, 1926): 14.

By the 1920s, precision appeared in articles on warfare, law, sports, and music; consumer products that used it as a catch-word include pens, syringes, scales, gauges, eyeglasses, cameras, tailored suits, gloves, shoes, watches, refrigerators, chairs, sewing machines, pianos, rifles, and radios (Fig. 3). Surprisingly, these ads reveal that precision was never antithetical to craftsmanship. Whether selling fashionable clothing or mechanical instruments, the term could describe the care of a worker’s touch or the expert inspection of a human eye. What’s more, precision had a history long before the Industrial Revolution. Since the 16th century, it has referred to a person’s moral sensibility, once describing the rhetorical prowess of a great orator or the pious behavior of a preacher. My work explores the undiscovered commonalities between Precisionist art and the older senses of precision, which continued to bubble up in unexpected places like Moore’s eccentric and exacting poetry.