Music in Circles

Phillips Music

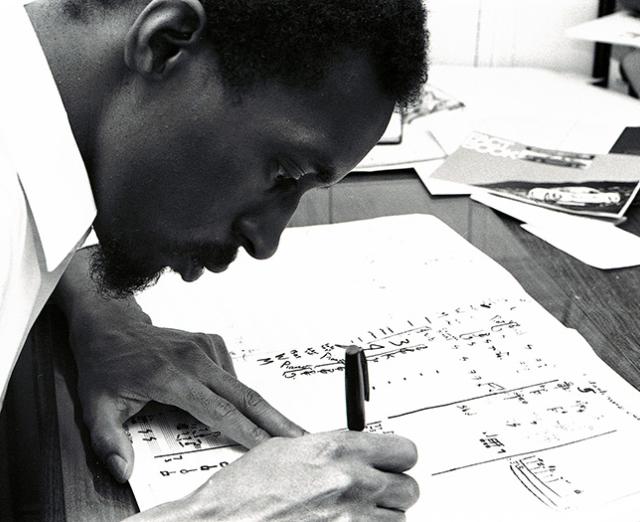

On November 18, during their Sunday Concert at the Phillips, Trio Zadig performed a program of piano trio works by Maurice Ravel, Benjamin Attahir, and Leonard Bernstein (arranged by Bruno Fontaine). Director of Music Jeremy Ney reflects on Asfar by Benjamin Attahir, composed in 2016 and given its DC premiere at The Phillips Collection.

The 29-year-old French-Lebanese composer Benjamin Attahir trained in composition at the Paris Conservatory under teachers Marc-André Dalbavie and Gérard Pesson. His music received early support from the late Pierre Boulez, whose encouragement was formative to the composer’s development. Attahir’s already mature compositional voice does not, however, fit within a neat continuum of the generation of French composers after Boulez whose music is so closely embedded within the technological high-modernism and experimentalism of IRCAM (the musical research institution Boulez founded in Paris in 1977). Rather, Attahir’s music is more fluid, exploring the Middle Eastern influences of his own heritage, a broad tableau of French music old and new, and gestures toward 20th-century Russian neoclassicism. Impossible to pin down precisely, Attahir’s sound world is hybrid and elusive, interwoven with influences yet never divisible into discrete categorization. His diverse musical imagination has been championed by figures such as Daniel Barenboim, who premiered the composer’s 30-minute orchestral work, Al Fair, in September 2017 during a concert that marked the opening of the Pierre Boulez-Saal in Berlin.

Asfar for piano trio is emblematic of Attahir’s inventive collage-like approach to composition. It begins forcefully with an unsparing separation of the ensemble; powerful chords in the piano are set against coarse unison string statements. These two sonic densities—one percussive, one melodic—seem to be locked in a struggle to find a common voice. Attahir sustains a hard-edged, jagged quality to the opening of the piece, which never falters in its consistent, driving pulse. A two-note melody, traded between instruments, tries to sustain a singing quality above an unsettling ostinato. Yet this fragment—barely melodic at all—cannot find a foothold within the relentless march of rhythmic intensity. A sudden stream of notes (repeated at octave intervals) moves down and then up the piano’s register, seemingly indicating a new direction. Yet it gets stuck, circling in on itself in a musical short-circuit. Attahir then creates an even wider closed loop, shocking the piece back to its origins in an unrelenting Attacca statement of the opening material.

The perpetuum mobile nature of Asfar then begins to fragment further, its rhythms becoming taut and constricted, with silence as well as sound beginning to mark the work’s sense of inner struggle. The episodic nature continues toward a central section that becomes more hushed and subdued, with flashes of what sounds like melodies inflected by Middle Eastern tonality. But what are they? Attahir’s gestures are so ambiguous and subversive that they resit being deciphered. The piece seems to conceal itself within a dense web of different ideas and motifs, each one vying for significance. The whole effect feels like a vast constellation of scattered memories, layering on top of each other in an aural palimpsest.

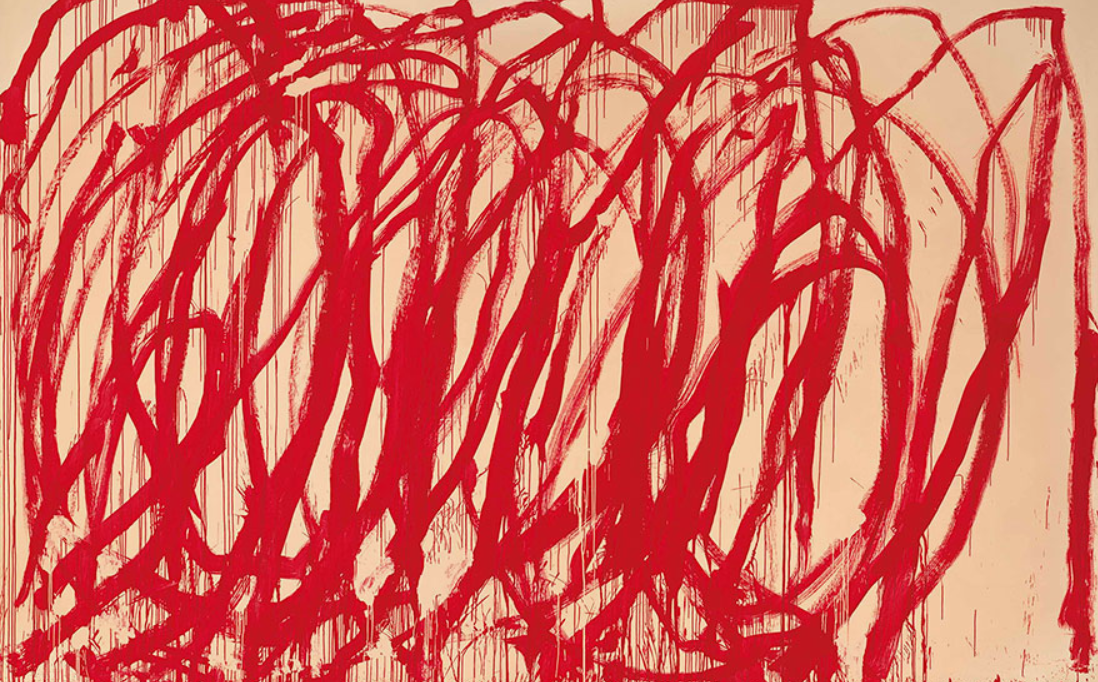

Attahir briefly draws the music toward a barely audible whisper, with the piano’s bass timbre flooded with the dark hue of reverberant harmonics. Drawing downward appears to bring us closer in, away from the shock and awe toward something more intimate, fragile, and revealing. Yet it proves merely a conceit as the inevitable, obliterating effect of the opening material returns. Bringing the piece to its close, Attahir toys with a final four note theme, which loops and eddies like a child scribbling circles on a page, or (perhaps) spirals around itself with the gestural ductus of artist Cy Twombly’s famous red Bacchus paintings.

Cy Twombly (1928-2011), Untitled, 2005, 128 x 194 ½ in. This work was offered in the Postwar & Contemporary Art Evening Sale on November 15, 2017, at Christie’s in New York.

—Jeremy Ney, Director of Music at The Phillips Collection