Listening to The Dandy

Phillips Music

We appear to know what we see in Nils Dardel’s 1918 painting The Dying Dandy: an impeccable and cultivated young man in the throes of an apparent death, albeit an indulgent and luxuriously choreographed one. It must be death, for the Dandy—the very epitome of vanity and frivolity—to be unable to gaze upon his own self-image is an aesthetic negation. The mirror is the Dandy’s portal to the sublime—as Baudelaire writes, he must “live and sleep” before it. An opulent death is thus the only way; adorned in silk and fastidiously dressed, death is the final act of performance, a means to preserve one’s image and reputation, without any of the vulgarity of the act itself. There is an irony to Dardel’s Dandyism too: an artist who flirted with Cubism and Surrealism and steeped himself in the ferment of the Parisian avant-garde. Do we read the painting biographically, as a symbolic snapshot in time of his own ill-health? Or is it less literal and more detached—a metaphor for Romantic individualism or a cipher for the artist’s dislocation from society? The rich, idle, indolent fakery of Dandyism? Or the witty, bohemian aesthetic of Wilde? Dardel seems to play with the paradox, rendering a series of possible meanings. Why not—it is art after all—not life.

A contemporary of Dardel’s who similarly toyed with the fluid concepts of Dandyism was Erik Satie, whose Three Distinguished Waltzes of a Jaded Dandy, composed in 1914, was performed at The Phillips Collection during a Sunday Concert on October 21 by pianist Pedja Mužijević. Satie’s three waltzes are miniatures: little perfume bottles and buttonholes of music, titled “His Waist,”“His Spectacles,” and “His Legs.” To accompany each piece, Satie contributes absurd inscriptions: “He pays himself a nicely fitting compliment.” “A great sadness comes over our friend: he has lost the case for his spectacles!” “They’re nice straight legs…He wants to carry them under his arms.” The music seems to have everything and nothing to do with Dandyism; Satie approaches his supposed subject with the blasé attitude of a humorist, creating the bait of meaning through allusion but simultaneously withdrawing it through a surrealist’s sleight of hand. How can the music itself convey such specificity? Satie mocks the very idea. The irony is Wildean then in its sly and impish conceit, “jaded” about the very idea of music as anything other than the embodiment of itself. Satie’s Waltzes are very much like Dardel’s extravagant Dandy then, obsessed with the very purity of their own characteristics, stubbornly refusing to be reduced to words or to one single meaning.

—Jeremy Ney, Director of Music at The Phillips Collection

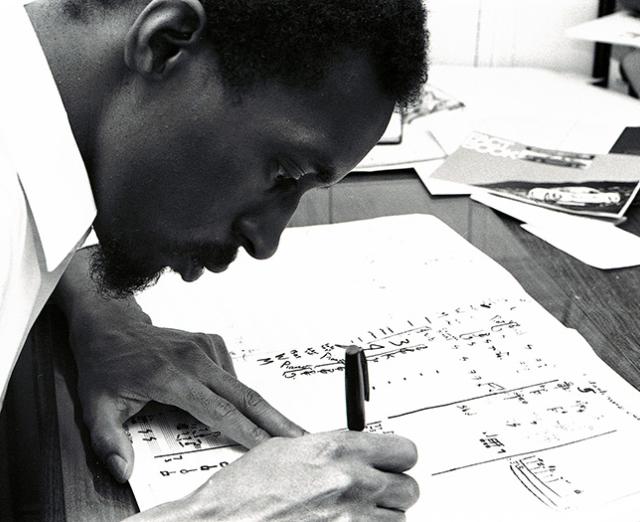

Listen to Pedja Mužijević perform Satie’s Three Distinguished Waltzes of a Jaded Dandy:

And see The Dying Dandy at The Phillips Collection in Nordic Impressions: Art from Åland, Denmark, the Faroe Islands, Finland, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden, 1821–2018 through January 13.