The Whistler in the Room

Exhibitions & Events

Noah Stevens-Stein, Director’s Office Intern, on the relationship between William Merritt Chase and James Abbott McNeil Whistler.

William Merritt Chase, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, 1885. Oil on canvas, 74 1/8 x 36 1/4 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of William H. Walker, 1918

Every time I walk from my desk to the library, I pass through the Phillips’s new exhibition, William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master. I always make a point to stop by one portrait: an 1885 portrait of James Abbott McNeill Whistler, hung beautifully in the high-ceilinged Wurtzel Gallery. It’s a work that stands out for its distinguished sitter and for Chase’s distinguished artistry. Whistler was also a portraitist of the late 19th century, Chase’s senior by some years. Chase greatly admired him, and sought Whistler out in London early in his career. The two immediately became friends, and Whistler suggested that they paint each other’s portraits.

The picture in this exhibition, which Chase described to his wife as promising “to be the best thing”[1] he ever did, is what resulted from Whistler’s urging. Unfortunately, their friendship was short and ended bitterly. Whistler described the portrait as a “monstrous lampoon,”[2] though his Brown and Gold (Self Portrait) (1895-1900) seems to echo Chase’s earlier image. Both Whistler and Chase are important to The Phillips Collection outside of this 2016 retrospective exhibition.

Duncan Phillips acquired Whistler’s Miss Lillian Woakes (1890-91) in 1920 (which is currently on view in another gallery in the museum) and Chase’s Hide and Seek (1888) in 1923. Whistler’s Miss Lillian Woakes is small, dark, and extraordinarily powerful. Whistler’s first biographer, Joseph Pennell, described it as “one of the most successful—certainly the most beautiful [works] Whistler produced after his marriage.”[3] Included in the Knoedler Galleries group of Whistlers in 1914, a New York Times critic praised it: “Above enchanting draperies rises the head, soundly modelled and rich in humanity.”[4] Whistler can be a hard artist to classify due to his whimsicality, exploration, and innovation. About 300 of his works can be found across the city at the Freer|Sackler. Its founder, Charles Lang Freer, collected Asian art as well as Whistler and other American artists; Whistler due to his Asian influences—this is particularly evident in Whistler’s Peacock Room.

Whistler’s paintings also hang beside Thomas Eakins’s in the American galleries at The National Gallery of Art. Phillips seems to have seen Whistler as a link to the realism of Gustave Courbet and Edgar Degas, and the naturalism of Diego Velázquez. In the 1930s and 40s, Phillips usually displayed Miss Lillian Woakes next to French masters: Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Honoré Daumier, Degas. More recently, the portrait has been hung with American contemporaries: Eakins, George Fuller, Winslow Homer, and George Inness.

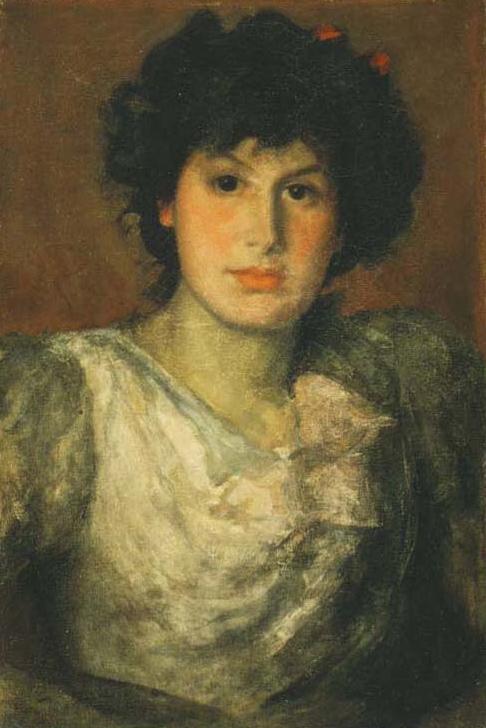

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Miss Lillian Woakes, 1890-01. Oil on canvas, 21 1/8 x 14 1/8 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC

Phillips was keen to distinguish his Whistler from those held at the Freer. In A Collection in the Making, he catalogued her: “Miss Woakes, however, is not a mere pretext for a color scheme, and not a Japanese conception of the figure as an arabesque, nor a graceful form enveloped in shadowy air. She is a robust blooming English girl in whose vitality and subtle spirit the artist seems to have forgotten himself, striving only for the plastic ‘presence’ and for an expression of the ‘eternal feminine.’” When you come to visit William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master at the Phillips, ensure you take the time to go downstairs and see the lovely Miss Lillian Woakes as well.

[1] William Merritt Chase to Alice Gerson, August 8, 1885, reel N69-137, frame 538. Chase Papers.

[2] Smithgall, Elsa, Erica E. Hirshler, Katherine M. Bourguignon, Giovanna Ginex, and John Davis. William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016.

[3] Joseph Pennell to Knoedler Gallery, n.d., Knoedler Archives, New York. [4] W. L. Lampton, “Art Notes,” New York Times, Apr. 5, 1914, sec. 3, p. 14.